You are here

The story of AIDS, from fear to fight

It was in 1982 that Anne-Marie Moulin,1 then a specialist in parasitology, saw her first AIDS patient, although the disease did not yet have a name. He was dying. “During his final days, he was needlessly harassed by people trying to get him to confess to being a homosexual. But in fact this researcher had just returned from a mission in Haiti. Following an accident there, he had been given a blood transfusion and contracted the as yet unknown virus,” recalls the CNRS research professor emeritus at the SPHERE laboratory,2 where she continues to study emerging diseases. This tragic tale reveals the extent to which AIDS patients were stigmatised from the outset.

“In 1981, epidemiologists in North America developed an initial theory of the origins of AIDS, which was routinely referred to as ‘4H disease’, because it affected heroin addicts, homosexuals, haemophiliacs and Haitians. Haemophiliacs aside, these terms refer to categories of people who were already discriminated against,” comments health anthropologist Sandrine Musso, from the CNELIAS.3

It was in June 1981 that the general public first became aware of AIDS, when Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report published an article revealing that five patients had been treated for a form of pneumonia that only appeared when the immune system was severely weakened. In the months that followed, the disease was dubbed “acquired immunodeficiency syndrome”, or AIDS.

However, its history goes back much further. “From old serum samples, we today believe4 that it all started in the 1920s, in Central Africa, where the virus is thought to have passed from monkeys to humans. The pathogen then took a long time to adapt and spread. It probably emerged as a pandemic as a result of students travelling between the Central African Republic, the Congo and the rest of the continent, followed by exchanges of intellectuals and professionals between Africa and Haiti,” Moulin explains.

“AIDS was initially thought of as an epidemic affecting the margins of society”

Why then was the disease associated with particular social groups? “The first cases, in 1981, were identified in male homosexuals because they were already subject to special medical surveillance. In fact, sexually transmitted infections had been spreading, following a wave of sexual liberation during the 1970s,” notes the socio-anthropologist Christophe Broqua, a member of the African Worlds Institute (IMAF).5

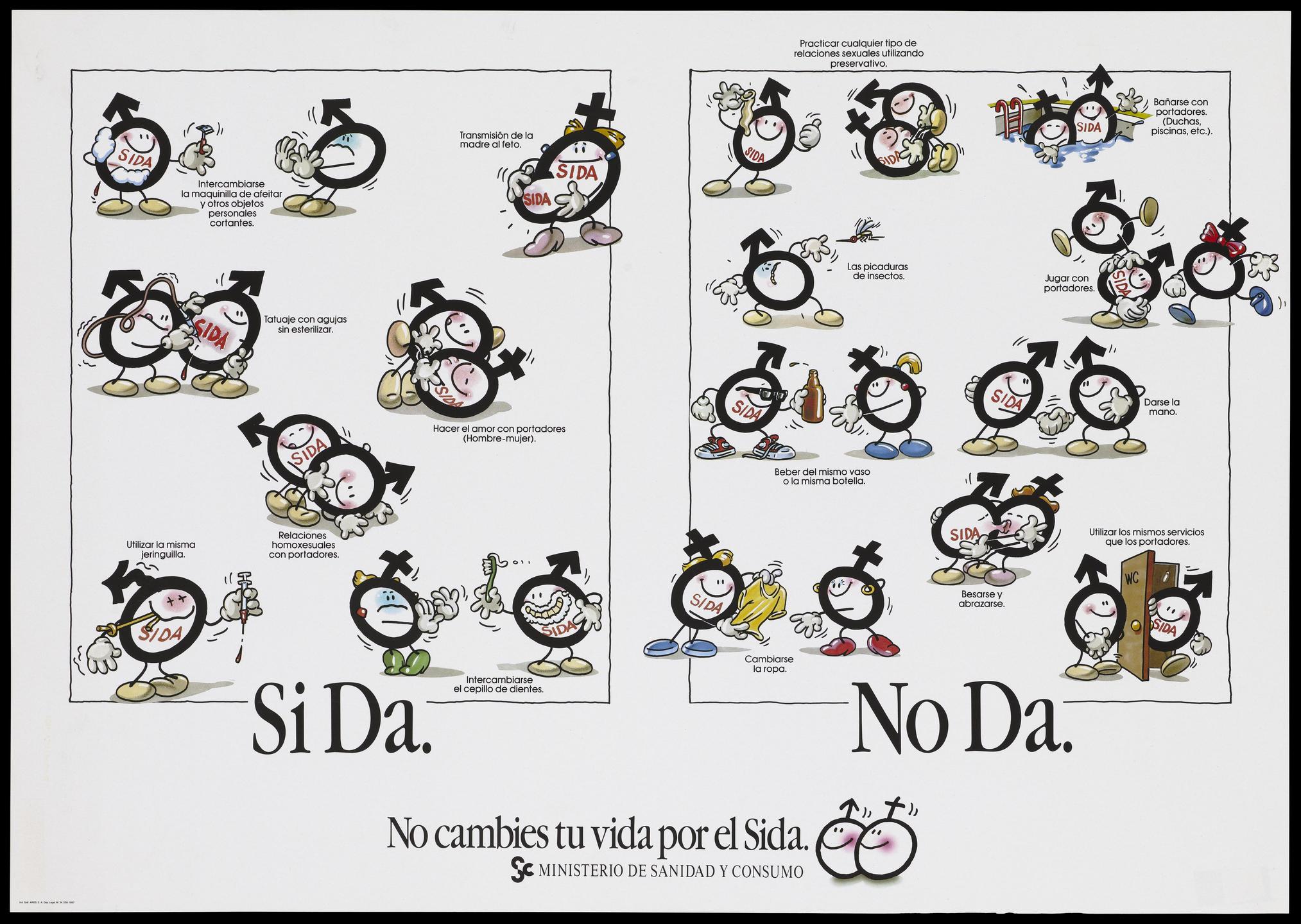

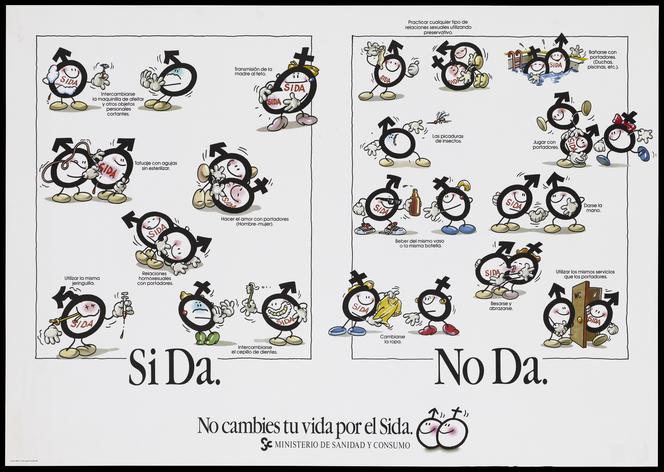

“In addition, HIV has a distinctive characteristic: although it can affect anyone, it spreads preferentially in certain groups through specific practices: among male homosexuals because transmission is facilitated by the practice of anal penetration, and among intravenous drug users, through needle sharing. For these reasons, AIDS was initially thought of as an epidemic affecting the margins of society, even though it was subsequently shown that heterosexual transmission had been developing simultaneously in Africa,” Broqua points out. “However, this aspect was widely underestimated in developed countries. As a result, women were generally left out of prevention campaigns, except for mothers in the context of mother-to-child transmission, and female prostitutes,” Musso says.

In the 1980s, the disease, frequently referred to as “gay cancer”, led to considerable stigma. Broqua recalls that attacks became increasingly widespread throughout the 1990s due to “rhetoric that unfairly accused gay activists of irresponsibility because they had for a time denied the existence of the illness. However, I believe this search for scapegoats is inherent to any epidemic”.

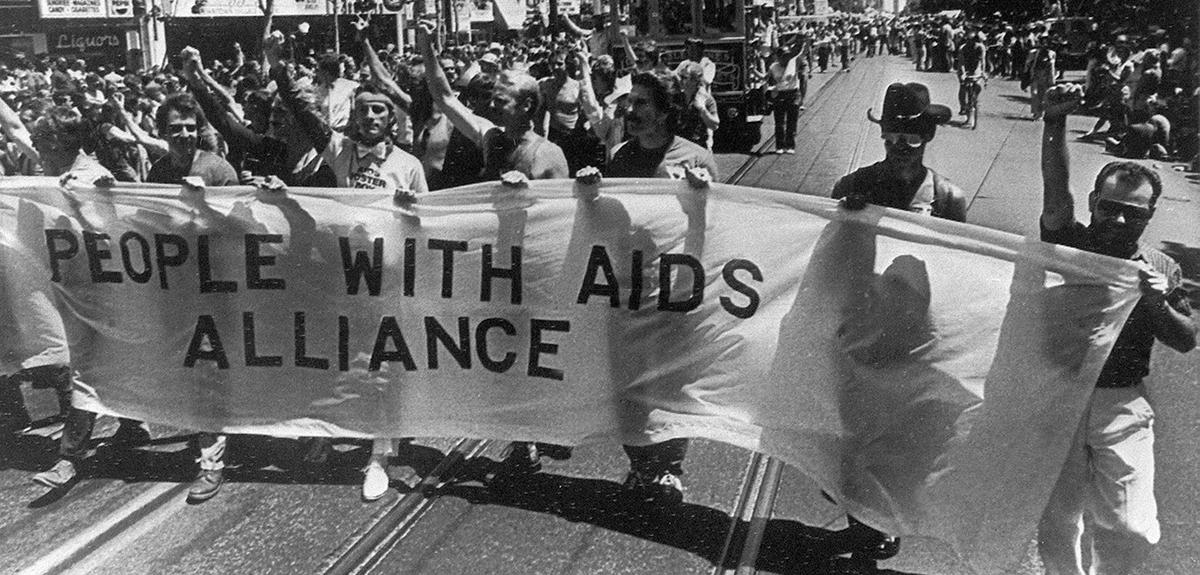

Patient expertise and AIDS activism

The AIDS pandemic gave rise not only to fear, but also to new inclusive practices. Initially, medicine was powerless. “Right from the start, many people with AIDS asserted their expertise on the basis of their experience, set up therapy clubs and demanded to take part in political decisions involving them,” Musso says.

In 1985, screening tests were introduced. While only AIDS sufferers had been accounted for until then, this raised the issue of HIV-positive people, who can normally live ten years or so between infection and the onset of the disease. “Some French politicians called for the setting up of a register of HIV-positive individuals. In 1991, this request was rejected by France's National AIDS Council,6 which advocated a public health approach based on law,” Musso adds.

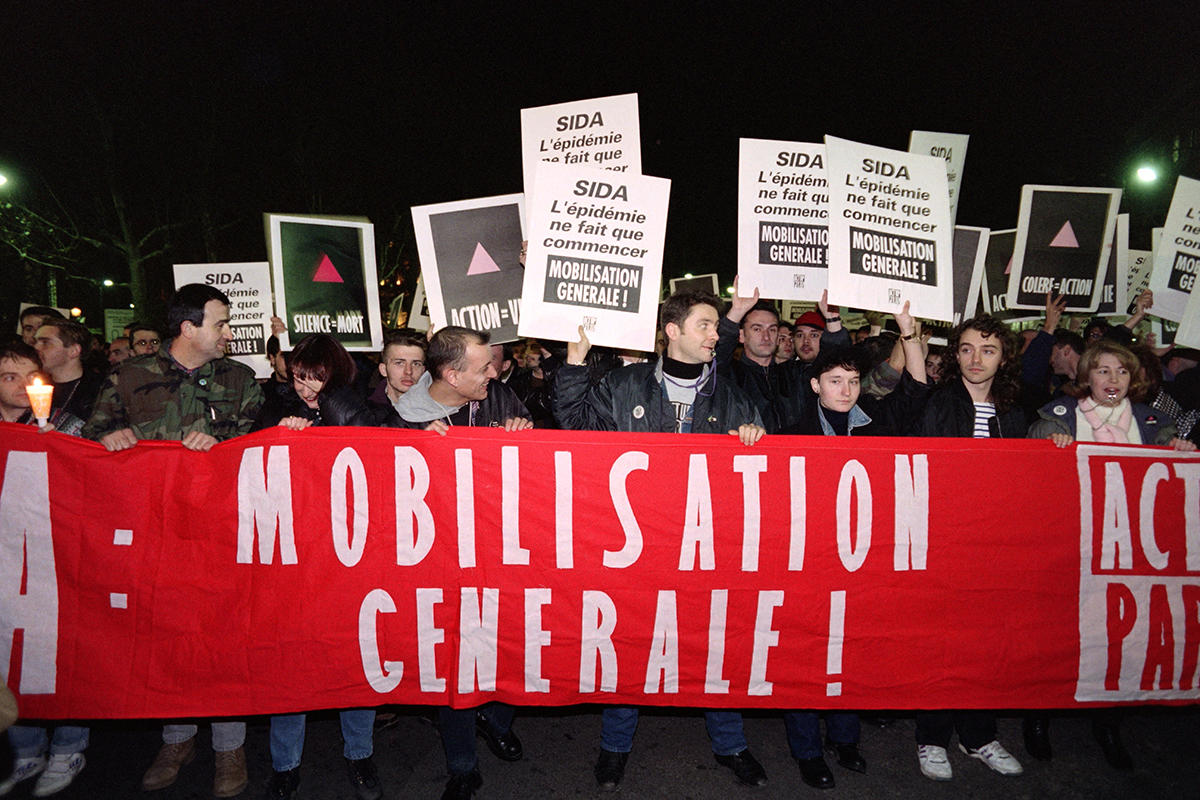

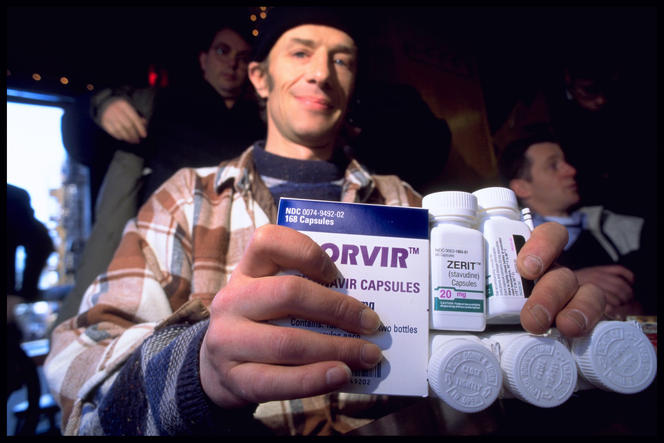

AIDS associations, often led by gays, played a leading role in the implementation of policies and the development of treatments. “With research rapidly moving forward in the 1990s, activists put pressure on scientists and the pharmaceutical industry: because of their knowledge of the treatments being trialled, patients took action to make them available more quickly,” explains INSERM researcher Gabriel Girard, from the SESSTIM.7 Within AIDS activism, a highly critical movement emerged around the Act Up association, founded in 1987 in the United States. “Initially set up to denounce the injustices linked to the epidemic, Act Up challenged the medical establishment head-on.”

Recording activists' battles and victories

Broqua, who wrote a thesis about this association, believes that “Act Up's most important achievement is their work on how the public perceived the disease and the various groups impacted by it, especially gays”. The socio-anthropologist points to the stark contrast between the image of this organisation in the 1990s and the one it has today: “When the film ‘120 Beats Per Minute’8 was released in 2017, Act Up was hailed as having played a heroic role in the fight against AIDS, whereas at the time it was slammed by both politicians and some anti-AIDS activists, as many saw it as violent and communitarian.”

Recording this battle was a crucial issue. “In 1997, Act Up set up a group specifically focused on archives and documentation, thus giving the collective memory of the struggle a role that was both practical and militant,” says anthropologist Renaud Chantraine,9 a PhD student at the EHESS, who helped to design the upcoming exhibition VIH/sida, l'épidémie n'est pas finie! HIV/AIDS, the epidemic is not over! at the MUCEM museum of civilisations of Europe and the Mediterranean in Marseille (southeastern France). “We have attempted to establish a written record of the objects held in the museum's collections, by bringing together carers, activists, academics and people living with HIV,” the researcher explains.

Through their initiatives, organisations and projects such as Act Up, AIDES, the AIDS Memorial Quilt, and the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, chalked up a number of victories, including full health insurance coverage for people infected with HIV in the 1990s, and the free distribution of generic drugs in developing countries since the 2000s. “Much more recently, they obtained the lifting of the ban on funeral care for people infected with HIV,” Broqua adds.

Public perception of the disease has also improved with the emergence of treatments. Triple therapy, which first became available in 1996, has enabled those infected to maintain a near-normal life expectancy, albeit with significant side effects. “At that point, the condition lost its plague-like status,” Musso points out.

At the same time, doctors regained a central role in the care and prevention of HIV, reinforced in the late 2000s by the launch of prophylactic treatments. “Since 2008, it has been shown that these antiretroviral therapies, already used successfully to prevent mother-to-child transmission, have protective properties with regard to sexual transmission,” Broqua explains. “Today, people living with HIV know that, with treatment and an undetectable viral load, they no longer transmit the virus sexually. This has led to a complete change in the behaviour and attitudes of infected individuals and those around them.”

Inequalities persist in terms of prevention and treatment

AIDS has become a chronic disease, but not everyone across the world is on an equal footing. “In France, all known HIV-positive individuals are treated. But in Africa, for example, only some 30% of them receive treatment, which means that there are still children being born there with HIV,” Moulin stresses. So why is there such a gap?

“The fight against AIDS has led to agreements allowing governments to obtain exemptions from patent law when a pandemic threatens their populations, which is without doubt a step forward,” concedes the former chair of the ethics committee of the French National Research Institute for Sustainable Development (IRD), who nonetheless emphasises that “many African countries continue to suffer from stock shortages, partly related to political instability”. In addition, the virus is developing increasing resistance to conventional anti-HIV treatments in countries where the most recent drugs are not always available.

Access to treatment is not the only problem. “Although a large proportion of infections in Africa occur through heterosexual contact, transmission is particularly high within certain groups such as sexual minorities,” says Broqua, who has been investigating AIDS and homosexuality in West Africa for the past twenty years or so. “The situation is not straightforward in this region, where such minorities are repressed. Prevention in some North African States, where there are sometimes no gay groups, is just as tricky as in sub-Saharan Africa. Even though these countries have committed to providing free therapy, they do not fund prevention in the communities most affected by HIV.”

“Even in France, people continue to die of AIDS, often because they found out that they were HIV-positive at a very late stage,” Girard notes. “The extent to which people use prevention methods still largely depends on living conditions and the social, cultural and political environment. When one’s priorities are housing and food, getting treatment is of secondary importance.”

AIDS and health democracy

After 40 years of struggle, has the fight against AIDS taught us how to manage a health crisis? “People with COVID-19 were given no say in the matter, and yet the lessons learned from AIDS could shed light on the role of patients and civil society in addressing the issues raised by the epidemic,” believes Musso, who contributed to the latest issue of the journal Anthropologie et santé (Anthropology and health), dedicated to health crises.

Moulin, who recently wrote on the subject in La Revue de santé publique (The public health review), is of the same opinion: “Many researchers have protested against the Government's approach to the COVID-19 pandemic, which takes no account of what we have learnt from AIDS. Jean-François Delfraissy, former director of the French Agency for Research on AIDS10 and currently head of France's Scientific Council, said he had tried to convince the Presidency to conduct a broad popular consultation, but that his proposals were left unanswered. In the end, the lessons of democracy and civic-mindedness drawn from the AIDS experience have hardly been put to use during the COVID-19 epidemic.”

- 1. Anne-Marie Moulin is a doctor specialising in parasitology and tropical medicine, who also holds an agrégation (France's highest teaching diploma) in philosophy. From 1999 to 2002 she was director of the health/social sciences department of the French National Research Institute for Sustainable Development (IRD), and from 2002 to 2006 chaired the Board of the French National Agency for Research on AIDS (ANRS – now ANRS-Emerging Infectious Diseases).

- 2. Laboratoire Sciences, Philosophie, Histoire (CNRS / Université de Paris).

- 3. Centre Norbert Elias (CNRS / EHESS / Aix-Marseille Université / Avignon Université).

- 4. Jacques Pépin, The origins of Aids, Cambridge University Press, 2nd edition 2021.

- 5. CNRS / Université Paris 1 - Panthéon-Sorbonne / EHESS / IRD / Aix-Marseille Université).

- 6. The French National AIDS and Viral Hepatitis Council was set up in 2015 to replace the former National AIDS Council, created in 1989. It advises on all the problems posed to society by these two conditions, and submits proposals to the Government.

- 7. INSERM / IRD / Aix Marseille Université).

- 8. The film “120 Beats Per Minute”, by Robin Campillo, was released on 23 August, 2017. The action takes place in the early 1990s when, with AIDS killing people for nearly ten years, the activists of Act Up-Paris intensified their actions in order to combat widespread indifference.

- 9. Renaud Chantraine is working in particular on a re-reading of the fundraising survey conducted between 2002 and 2006 by the museum of popular arts and traditions-French centre for ethnology, with organisations and projects such as Act Up, the AIDS Memorial Quilt, the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, and AIDES.

- 10. Set up in 1988, the French Agency for Research on AIDS – now ANRS--Emerging Infectious Diseases – aims to unite, coordinate, promote and fund public research on HIV and viral hepatitis.

Explore more

Author

Specializing in themes related to religions, spirituality and history, Matthieu Sricot works with various media, including Le Monde des Religions, La Vie, Sciences Humaines and even Inrees.