You are here

"Protecting democratic debate against hatred and lies"

What is blasphemy?

Thomas Hochmann1: The word is often used to designate rhetoric that is hostile or disrespectful towards a dogma, a person or an object venerated by the followers of a religion. The prohibition of blasphemy has deep historical roots. In ancient Greece, lack of respect for the gods was punishable by death. This was one of the accusations levelled against Socrates at his trial. The Bible (book of Leviticus) stipulates that ‘Whoever blasphemes the name of the Lord shall surely be put to death. All the congregation shall stone him’. In Europe, blasphemy carried a death sentence until the late 18th century. Certain cases in France left a memorable impression, like that of the young Chevalier de La Barre, who was beheaded in 1766 for desecrating a crucifix and not removing his hat in front of a religious procession. His execution shocked all of Europe, with Voltaire in particular expressing outrage.

When was blasphemy decriminalised?

T. H.: According to Article 10 of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, in 1789, ‘No one may be disturbed on account of his opinions, even religious ones’. The Penal Code of 1791 includes no infractions for blasphemy. Under the Restoration, in 1819 the legislation took a step backwards by making contempt of public and religious morals an offence, which made it possible, for example, to convict Pierre-Joseph Proudhon for a book in which he spoke of the ‘irrelevance’ of God. The enactment of the Law on the Freedom of the Press of 29 July, 1881 abolished this provision. In the 20th century, there were a few court decisions condemning posters accused of offending religious sensibilities, but these were isolated and soon-forgotten cases.

What is the situation in other countries?

T. H.: The European Court of Human Rights does not require the punishment of attacks on religious beliefs, but allows member states to make this choice. Nowadays, however, the EU countries that still have an anti-blasphemy law on the books almost never enforce it, even though the few cases that reach the courts tend to cause a stir. In Europe there is a very marked trend towards the repeal of such laws. On the other hand, blasphemy is punished in most Muslim countries (Algeria, Egypt, Iran, etc.), as well as in India and Myanmar (Burma).

The divide between societies that tolerate blasphemy and those that harshly repress it was in evidence at the United Nations throughout the early 2000s, with countries like Pakistan pushing for the adoption of resolutions denouncing the ‘defamation of religion' . In 2011 this wording was dropped in favour of a resolution countering ‘incitement to violence and violence against, persons based on religion or belief’.

Has the distinction between blasphemy and hate speech become a central issue?

T. H.: Yes, as we saw in 2007 during the prosecution of the lawsuit brought by Muslim organisations against the magazine Charlie Hebdo for the publication of caricatures. The drawings may have violated the tenets of Islam, which forbids the representation of the Prophet, and they undoubtedly shocked some Muslims, but they did not target them. A crucial point was the cover of that issue of Charlie Hebdo. A drawing by the cartoonist Cabu depicted Mohammed hiding his face, crying and lamenting, ‘It’s hard to be loved by morons…’ Cabu made sure to add a title that overlapped the drawing, becoming an integral part of it, reading, ‘Mohammed overwhelmed by fundamentalists’.

The court stressed that the insulting term was aimed at fundamentalists, a group that ‘cannot be confused with Muslims in general. The cover of the magazine only referred to Islamists, whose extremism drives the Prophet to despair upon seeing the distortion of his message’. The cartoon targeted them not because they were Muslims, but because they were fundamentalists.

On the other hand, French law does make it possible to punish insult, defamation and incitement to discrimination, hatred or violence directed against a person or group of persons because of their religion. For this reason, the polemicist Éric Zemmour has been prosecuted multiple times for his statements describing Muslim immigrants as ‘colonisers’, ‘criminals’ or ‘terrorists’. There is a crucial distinction between disrespect for a religious tenet or criticism of fundamentalists on the one hand, and on the other hand attacks against Muslims solely due to their religion.

What is the situation in the United States?

T. H.: In the United States, the scope of free speech is quite different. The basic idea is that the government cannot intervene to repress opinions or punish statements on the grounds that they could harm individuals. Consequently, declarations that offend religious believers cannot be penalised, but neither can hate speech. Neo-Nazis have been allowed to march in uniform in a city with a predominantly Jewish population, a homophobic sect was able to spout hateful slogans during the funerals of American soldiers…

A phrase by the European Court of Human Rights is often used: freedom of expression protects speech that ‘offends, shocks or disturbs’. But this description actually corresponds more closely to the legal situation in the United States! Protection is not absolute, but the cases in which it is permissible to limit expression are very narrowly defined, for example when a statement poses a clear and imminent danger of inciting crime.

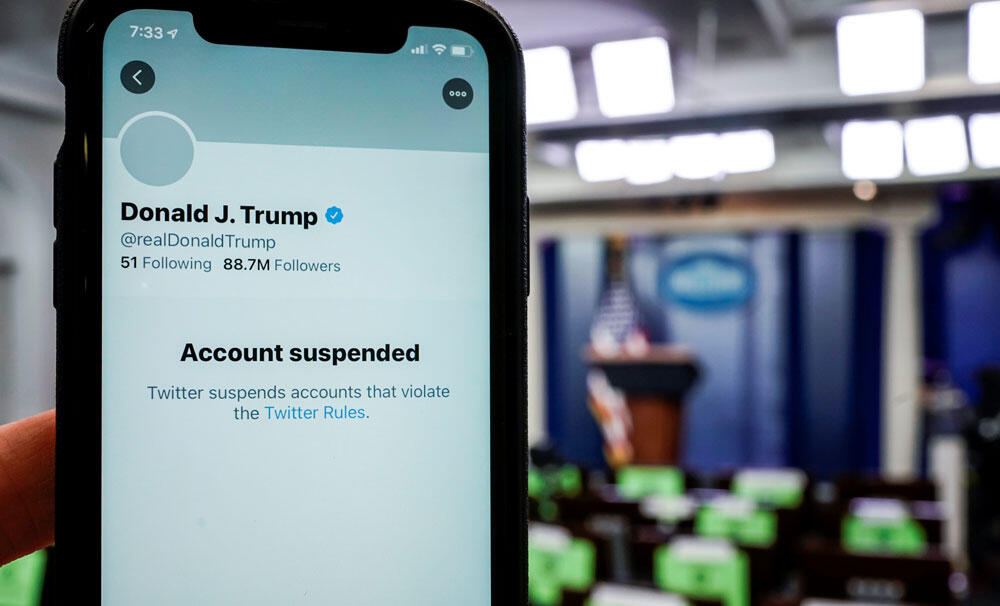

However, it should be noted that this principle, based on the First Amendment to the Constitution, only applies to public authorities. Private parties (individuals, companies, etc.) have every right to restrict other people’s speech. That is why Twitter was able to delete Donald Trump’s account after the attack on the Capitol: private entities are not required to uphold freedom of expression. The possibility of further regulating the power of social networks is now a topic of much discussion, in the United States and elsewhere in the world.

In Europe, the Digital Services Act, adopted in 2022, aims to better regulate the activity of these platforms, and especially to encourage them to remove illegal content without overly restricting freedom of speech. This question is addressed in particular by Pauline Trouillard within the Colibex Research Chair2.

In France, isn’t freedom of expression also regulated for television channels?

T. H.: The audiovisual media are subject to certain obligations, specified mainly in the law of 30 September, 1986 on freedom of communication and in the agreements that private channels must sign to receive authorisation to broadcast. For example, they are forbidden to show content that incites hatred or violence. They are required to promote the values of integration and solidarity, ensure the honesty and independence of information, and respect pluralism in the expression of currents of thought and opinion. Compliance with these obligations is monitored by an independent authority – formerly the CSA, now Arcom.

Today this system is being challenged by the appearance of channels that only give voice to one specific ‘current of opinion’ and do not always shy away from incitements to hatred or the manipulation of facts. The channels C8 and CNews have been reprimanded and sanctioned by Arcom a great many times3, but this seems to have no effect on their behaviour. Simple warnings and fines, for derisory amounts given the financial capacities of the companies in question, are apparently ineffective.

Arcom recently took things up a notch, announcing that it would not renew C8’s broadcasting licence in 2025 and imposing a penalty4 of €3.5 million due to a sequence in which the channel’s star host roundly insulted a member of Parliament for nearly ten minutes.

Why refuse to reauthorise C8 but not CNews?

T. H.: Indeed, CNews doesn’t meet its obligations any more than C8. To cite just a few recent examples, Arcom sanctioned the channel for comments made by speakers speculating on a link between immigration and the proliferation of bedbugs, claiming that the Warsaw ghetto ‘was meant to prevent typhus from spreading’, and describing unaccompanied minor migrants as ‘thieves’, ‘murderers’ and ‘rapists’.5 From a legal point of view, the non-renewal or revocation of the channel’s broadcasting licence would seem perfectly defensible.

Nevertheless, it’s not easy for Arcom to make such a decision. No one wants to be seen as a ‘censor’. The defenders of CNews invoke ‘freedom of expression’ very effectively to resist any attempt at regulation. In reality, freedom of expression does not mean the freedom to spread hatred or lies, but this is overshadowed by the rhetoric of ‘You can’t say anything anymore’. The indignant reactions in 2024 against a fainthearted ruling by the Council of State on the pluralism of currents of opinion6 were very revealing. All the judge did was remind people of the law, but some media equated this with dictatorship, the guillotine, and even the Dreyfus Affair! It is very intimidating. There are no doubt other reasons as well – such as economic blackmail, which links the funding of French cinema by the Canal+ group to the fate of CNews, as Camille Broyelle7 has explained.

Along with colleagues from Québec, you hold a research chair on the modern-day challenges of freedom of expression (Colibex). Can you tell us something about it?

T. H.: The Colibex project was launched by the CNRS and the Fonds de Recherche du Québec (FRQ, or Québec Research Fund – Editor’s note) to develop and facilitate investigations into the similar challenges facing freedom of expression in the contexts – closely related and yet quite different – of these two French-speaking environments. It aims to promote research and education in freedom of expression on a collaborative, interdisciplinary, international scale.

We conduct joint studies and make a special effort to share our findings on freedom of expression by organising seminars and symposia as well as operations involving the public. The chair encompasses four sections, each entrusted to a researcher from Québec or France. It also hosts PhD students and postdoctoral fellows. Our next event will be a symposium on emerging research, to be held at the Sorbonne on 23 and 24 January, 2025, with the theme ‘New perspectives on freedom of expression’ (in French).

Your upcoming book is subtitled Freedom of expression: the great diversion. Why this choice?

T. H.: In France and elsewhere, freedom of expression is often invoked to disseminate hate speech or disinformation campaigns. Attempts at regulation tend to be countered by the contention that ‘You can’t say anything anymore’. However, freedom of expression is not an abstract absolute principle, but rather a set of rules specifically conceived to protect democratic debate against hatred and lies. The book seeks to offer a clearer description of the applicable law, so as to combat the caricatural portrayal of freedom of expression. ♦

For further reading: “On ne peut plus rien dire...” – Liberté d’expression: le grand détournement (“‘You can’t say anything anymore…’ – Freedom of expression: the great diversion”), by Thomas Hochmann, 80 pages, Anamosa, to be released on 13 March, 2025.

- 1. Thomas Hochmann is a professor of public law and researcher at the CTAD centre for legal theory and analysis (CNRS / Université Paris-Nanterre) and co-holder of the France-Québec research chair on the modern-day challenges of freedom of expression (Colibex – CNRS / FRQ).

- 2. See https://libexpress.hypotheses.org/12821(in French).

- 3. See the list updated by Le Monde: https://www.lemonde.fr/les-decodeurs/article/2024/11/15/l-arcom-a-pris-5...

- 4. See https://www.arcom.fr/nos-ressources/espace-juridique/decisions/decision-...

- 5. Decisions to issue warnings or fines, March 2021, May 2022 and March 2024.

- 6. See https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/ceta/id/CETATEXT000049143773

- 7. See https://www.leclubdesjuristes.com/opinion/pourquoi-larcom-a-exclu-les-ch...