You are here

Marseille liberated!

The Liberation of France is not only the story of D-Day, that famous date of 6 June, 1944 when nearly 156,000 soldiers (mostly American, British and Canadian) stormed five beaches on the northwestern Normandy coast to drive the Germans out of Western Europe. The process actually began in November 1942 with the Allied landings in Algeria, followed by the liberation of Corsica in 1943, and continuing with the landing of French troops (the “First Army”) in the southeastern region of Provence on 15 August, 1944. It then took nearly a year of fighting to free the entire country before the German surrender on 8 May, 1945.

Although what was then still called the “French Empire” sent battalions of thousands of soldiers to land in Provence and liberate the cities of Toulon, Marseille and Lyon, the French army made only a small contribution to the Normandy landings. Still, our collective memory tends to retain the admittedly spectacular image of D-Day. “In fact, until the wars of decolonisation, the Provence landing was not completely forgotten,” reports Claire Miot, a historian at MESOPOLHIS1 and author of the book La Première Armée Française, de la Provence à l’Allemagne (1944-1945), published by Perrin. “People celebrated the liberation of France by its empire, colonial troops paraded on the Champs Élysées… The situation changed with the Algerian War, because after that there were two conflicting memories. It became difficult to glorify General Salan, who commanded the 6th Senegalese Rifle Regiment during the Provence landing and liberated Toulon, because he later took part in the Algiers putsch (1961) and headed the OAS (Organisation Armée Secrète, or Secret Army Organisation), fighting to maintain the status quo in French Algeria.”

In addition, relatively few of the First Army soldiers were from mainland France. The vast majority came from the empire, especially North Africa. How could we honour men who had saved the country but whom, in many cases, we then had to fight to keep our colonies? “Lastly,” Miot adds, “the liberation of the capital, Paris, is much more symbolic than the liberation of a provincial city.” The 2006 film Days of Glory, directed by Rachid Bouchareb, gave the colonial combatants their due, and prompted President Jacques Chirac to expedite the resolution of the issue of their pensions, which had been much lower than those of national veterans. However, it was not until the 70th anniversary of the Liberation that a French president, François Hollande, gave the Provence landing and the colonial soldiers a prominent place in his speeches.

Ten days of fierce fighting

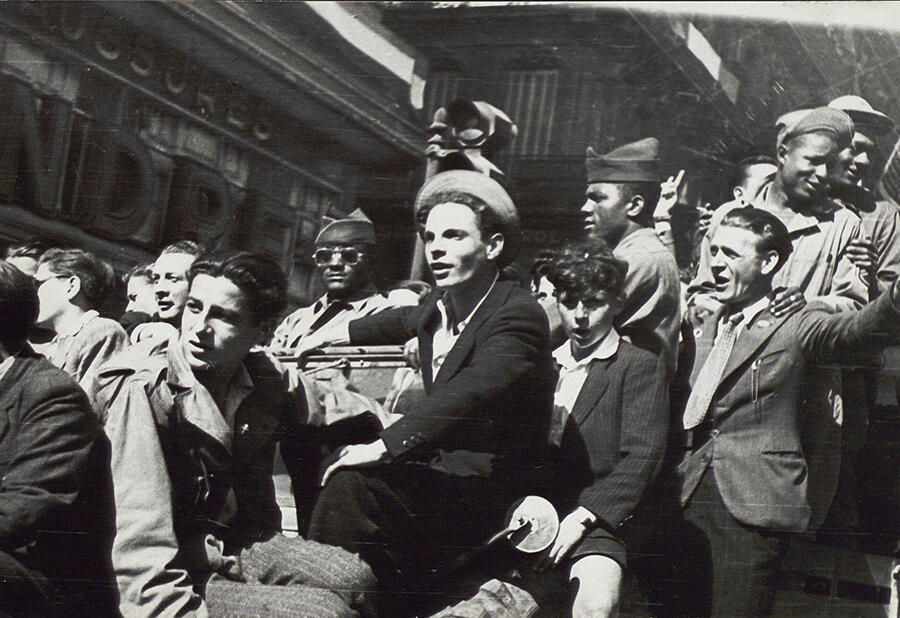

Hitler had ordered his forces to “fight to the death” to hold Toulon and Marseille, whose ports were vital supply points for bringing in Allied troops and equipment. It took ten days of fierce fighting to liberate the city. But Pirotte documented only the first day, 21 August, when the Résistance was fighting alone, assisted by some of the insurgent civilian population – hence the absence of First Army soldiers in her photos.

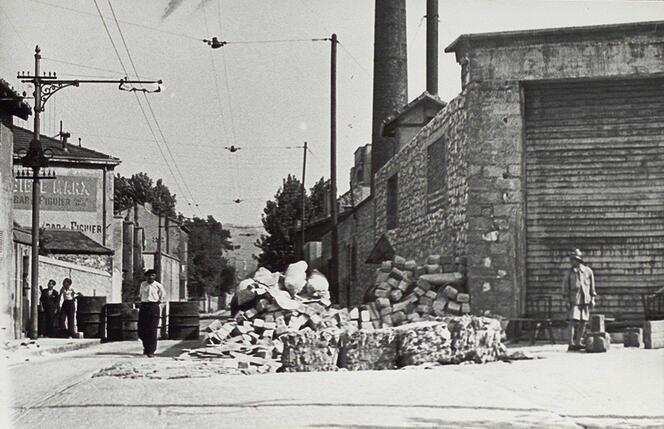

Besides its military importance, the liberation of Marseille had tremendous political significance. A wave of strikes had begun in late May. The SFIO (Socialist Party) held a majority in the region and the Allies, like De Gaulle, were wary of an insurrection that could hand over power to the communists, who were highly active in the Résistance. The army had not yet entered Marseille when a general strike began on 19 August, 1944, called by the communist union CGT, and on 21 August resistance fighters stormed the prefecture. “The Comité Départemental de Libération (regional liberation committee) was divided between the ‘politicians’, represented primarily by trade unionists, who were in favour of an immediate uprising,” Miot recounts, “and the ‘soldiers’ from the Francs-Tireurs Partisans (FTP), who showed more reluctance, emphasising their lack of manpower and weaponry, with 300 partisans and 280 machine guns – far from the 1,600 combatants estimated by the Allies, and in any case trivial compared with the 35,000 members of the French Forces of the Interior (FFI) in the Paris region.”

Barricades were erected throughout the city, and a large portion of the population, especially women, took turns helping the fighters and bringing them supplies. Faced with a situation disconcertingly similar to the revolutionary uprising of the Commune in 1871, General de Lattre de Tassigny, commander of the First Army, ordered General Monsabert, who had landed in Provence leading the 3rd Algerian Infantry Division (DIA), to halt his advance on Marseille. He wanted to wait for the resistance fighters, under increasing pressure, to ask for help from the regular army – which they did on 22 August. Monsabert’s troops then entered Marseille on 23 August and fought alongside the soldiers of the Résistance.

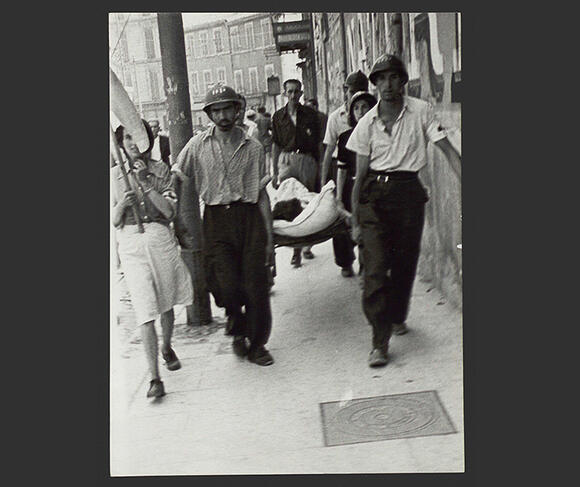

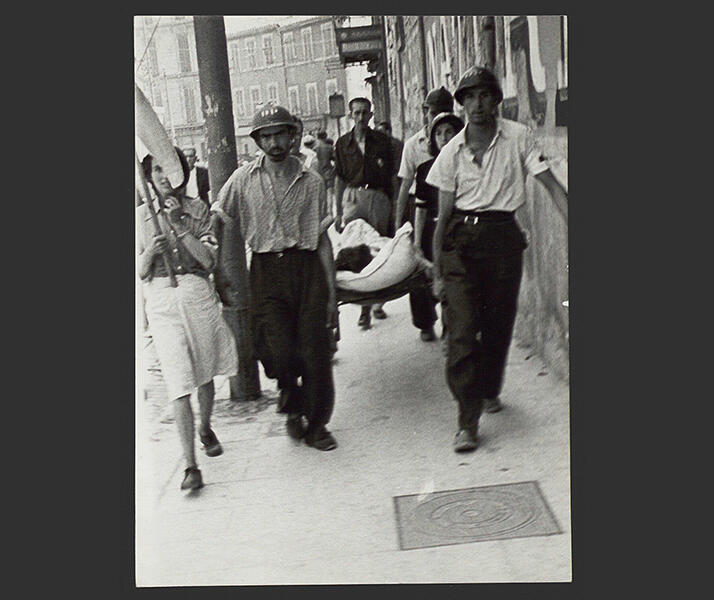

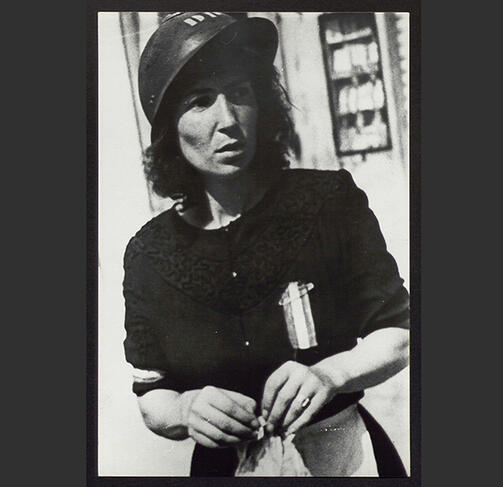

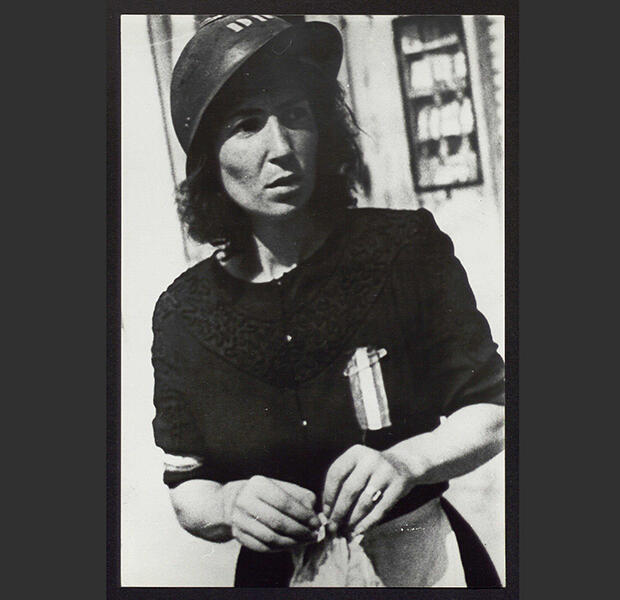

The photo shown above was published in the newspaper Combattre in 1945, on the first anniversary of the uprising. Captioned “Transporting a wounded man in the Endoume district”, it shows a woman carrying a white flag in the foreground, and between the two men another woman wearing a helmet, who would be photographed again in close-up. The same “helmeted woman” appears in another image taken by Pirotte a few days later, when she received a decoration from General Monsabert for her participation in the Résistance. Many of the women who worked for the Résistance would later join the regular army.

In April 1944, the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (AFAT) was formed as a branch of the French volunteer corps created by De Gaulle in London. “But note that they are called ‘auxiliaries’,” Miot comments. “In addition, they were always recruited specifically ‘to free men from non-combat functions’.” There were as many as 10,000 of them in the First Army, assigned to administrative and logistical posts: telephone operators, ambulance drivers, nurses, many recruited from the ranks of the Résistance as more and more territory was liberated.

“Women in the battle”

Published in the newspaper Rouge Midi on 3 September, 1944, under the title “Women in the battle”, the photo shown below evokes the traditional image of women as helpers and providers of childcare. But in the article it illustrates, Pirotte reminds us, in a nearly lyrical tone, that they played an active role in the Résistance, beyond the domestic realm: “I saw them at work, defying the law, hundreds of women transporting weapons, gathering intelligence, making identity documents. And then I saw them during the uprising, in barracks, factories and offices, bringing food to the combatants under a hail of bullets and bombs. I saw thousands and thousands of them, women of all social backgrounds and political convictions: workers, teachers, nuns who joined forces to organise hospitals and clinics, laundries and nurseries, food supplies for the starving population.”

Moreover, as Miot points out, “We must keep in mind that during this time women were outdoors, in the streets, at the barricades, alongside the fighters, contributing to what some saw as the ‘red peril’ of a population in revolt.”

After taking refuge on the hill of Notre-Dame de la Garde and in a section of the Vieux-Port (Old Port), the last German forces in Marseille did not capitulate until 28 August, 1944. The French army lost 1,825 men in the battle but captured nearly 11,000 prisoners. The civilian casualties, with some 200 killed and 500 wounded, also bear witness to the violence of the fighting. A huge parade was held to celebrate the unity of the population against the enemy. The “red peril” faded away. Resistance fighters, regular army soldiers, Europeans, North Africans, men and women, all played their part. Figuring prominently in the parade were goumiers, volunteer soldiers recruited from Moroccan tribes that the colonial authorities considered to be “natural warriers”.

Once again Julia Pirotte trained her lens on women, at the head of the parade of 29 August, 1944, brandishing slogans referring to the events and politics of the time: “Death to Pétain”, “Long live the school of freedom”. Did this reflect the fact that French women had just been granted the right to vote (although only in mainland France) by the Ordinance of 21 April, 1944? As the historian Fabrice Virgili points out, “The right to vote was presented as a ‘reward’ for their actions during the war, which was a way of not recognising the long struggle that women had waged to obtain this fundamental right of citizenship,” in particular through the suffragist movement, whose first group in France was founded in… 1876! ♦

-----------------------------------

Julia Pirotte, photographer and resistance fighter

Julia Pirotte (born Golda Perla Diament) was born in Poland in 1907, into a Jewish family of modest means. At a very young age she became active in the Communist Party, which led to her serving four years in prison between the ages of 17 and 20. To avoid further arrest, in 1934 she went into exile in Belgium, where she met Suzanne Spaak, a militant and future major figure in the Belgian resistance, who saved many Jewish children before being executed by firing squad in 1944. “Suzanne encouraged Julia to try a career as a photojournalist and gave her the camera, a Leica, that she used for all of her war reporting,” recounts Bruna Lo Biundo, curator of the exhibition “Julia Pirotte, photographer and resistance fighter” shown at the Shoah Memorial in 2023. Following the invasion of Belgium, Julia fled to Marseille, where she joined the MOI (immigrant workforce), which in the spring of 1942 represented the Marat detachment of the FTP-MOI (a resistance movement uniting foreign communist militants). Covertly, she served as a liaison officer and made false ID papers at home, all the while working overtly for the local press (La Marseillaise, Rouge Midi, etc.). On 21 August, 1944, she took part in the fighting and photographed her group of partisans during the uprising.

“The Battle of Marseille was the high point of my life,” she wrote in September 1944. “Like so many others, I had a score to settle with the Nazis; my parents and my entire family had been killed in the camps and the ghettos in Poland. I had no news of my sister, who was a political prisoner – I didn’t yet know that she had been executed by guillotine.” In Pirotte’s images of the fighting to liberate the city, women and resistance fighters are purposely placed in the foreground. After the war she continued her work as a socially conscious photojournalist, notably in Poland, where she documented the Kielce pogrom, the massacre of Holocaust survivors in July 1946. ♦

For further reading

Une Histoire du Débarquement et de la Bataille de Provence, (“A history of the landings and battle of Provence”), Passé Composés, to be released (in French) in August 2024.

Catalogue of the exhibition “Julia Pirotte, photographer and resistance fighter”, Caroline François and Bruna Lo Biundo, published by the Shoah Memorial, March 2023, 52 p. In French.

La Première Armée Française, de la Provence à l’Allemagne (1944-1945), (“The First French Army, from Provence to Germany (1944-1945)”), Claire Miot, Perrin, 2021, 454 p. In French.

- 1. Centre Méditerranéen de Sociologie, de Science Politique et d’Histoire (CNRS / Aix-Marseille Université / Sciences Po Aix-en-Provence).