You are here

Research on HIV has reached a turning point

What is the global situation regarding the epidemic?

Monsef Benkirane:1 The situation is stable if you consider the number of seropositive individuals, but it has not improved for several years. It is thought that 37 million people are infected by HIV throughout the world; a quarter of them without knowing. Huge efforts have been made regarding therapies, notably in Sub-Saharan Africa which alone is home to 25 million cases. These endeavours have enabled 26 million sufferers worldwide to receive treatment, which is twice as many as ten years ago. This has had a notable effect on the mortality rate of the disease: according to UNAIDS, 690,000 people died from HIV/AIDS in 2020, as opposed to 1.5 million annually a decade ago. Yet these results could be better.

Why do you believe we could do better from now on?

M. B.: We now have all the resources we need to put an end to this epidemic. First of all, triple therapies mean that patients have the same life expectancy as uninfected individuals, and also prevent them from transmitting HIV to their partners. Under treatment, the virus is undetectable in the blood, which shows that these drug combinations constitute excellent preventive tools. This is the well-known treatment as prevention (TasP) strategy, which has been promoted during the past ten years. In addition, pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) can be taken preventively by people exposed to a high risk of infection, such as sex workers for whom the use of a condom is not always possible. But we need to remain vigilant, because PrEP using Truvada does not guarantee 100% protection and should be reserved for use by those facing the highest exposure.

Thanks to all these treatments, it would only take two generations to wholly eradicate the epidemic if all infected individuals were treated appropriately. But it is not that simple, because as well as issues concerning access to therapies in countries with limited resources, there is a real problem regarding compliance to treatment, even in Europe. HIV infection remains a stigma in a number of nations, prompting people to hide the fact that they are seropositive. It is therefore impossible ensure correct and life-long monitoring of the treatment, even though a few days’ interruption is enough to trigger a viral rebound. For this reason, the priority when it comes to definitively ending this epidemic is to find a vaccine.

What inspires you about the research advances achieved since the epidemic started in the early 1980s?

M. B.: A mere fifteen years elapsed between the appearance of the first cases and the market release of triple therapies, which is absolutely phenomenal. Scientific advances have shifted HIV from a fatal infection that we did not understand, to a chronic disease. It is true that huge efforts were made in terms of both human and financial resources, but that’s not all. Research on HIV/AIDS was extremely well coordinated. Research agencies, organisations such as Sidaction in France, scientists, clinicians and above all patients moved forward, hand in hand. It was a remarkable enterprise that should have been an inspiration for the management of the Covid-19 crisis, which was addressed haphazardly and with no roadmap.

You underline the particular role played by patient associations...

M. B.: The way research on HIV was organised was its strength, and to a great extent this was due to the patient associations and activists who relentlessly spurred on the scientists, and continue to do so to this day. These were people who were interested in the science: they asked us to explain everything, for example the mechanisms of the infection, or the mode of action of antiviral drugs, etc. It is thanks to their insistence, and because they were never satisfied and asked for a better quality of life, that we have continued to improve therapies: from twenty tablets daily with numerous side effects, the medication has now been reduced to one tablet a day. But that’s still not enough: scientists are now working on a long-lasting treatment in the form of a monthly injection… and perhaps, in the near future, one injection a year. However, research has now reached a plateau: although we are perfecting existing care, we are no longer advancing on a definitive cure for the disease. Specialists are struggling with the cellular reservoirs in which the virus remains dormant.

What about research on these cellular reservoirs that are not eradicated by existing treatments?

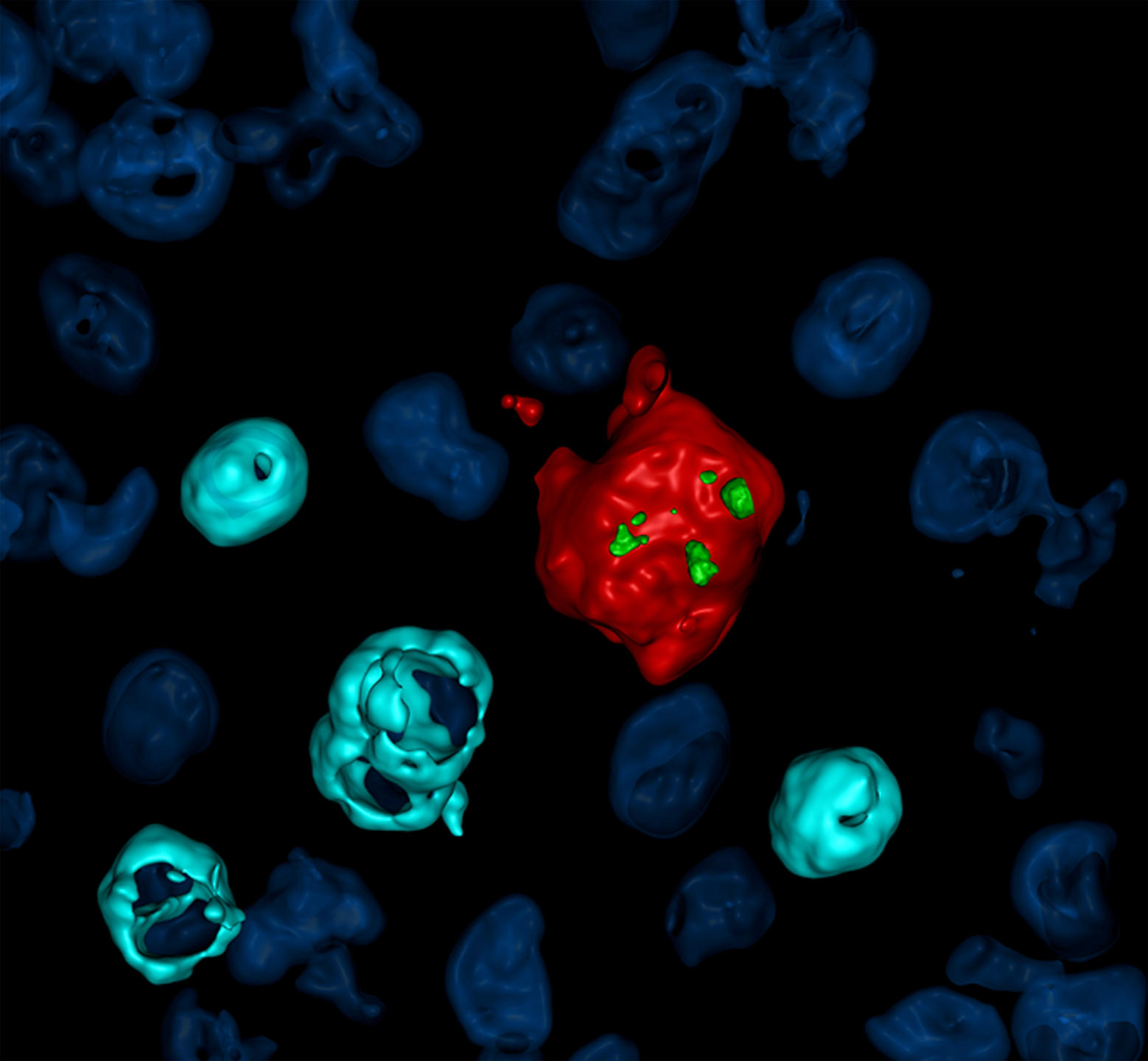

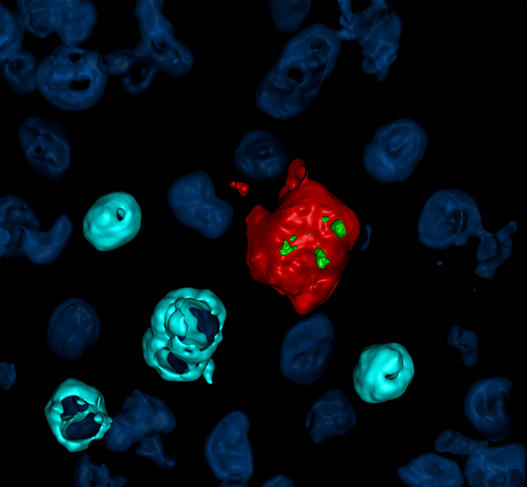

M. B.: We are progressing, but no longer at the speed we became used to during the early years of the HIV epidemic. Work on cellular reservoirs is indeed complicated by problems of access to these rare cells where the virus remains latent, protected from treatments and the immune response. One advance seen in recent years concerned our ability to quantify the reservoir that was actually functional, using new technical and experimental approaches. When searching for the viral DNA, we observed that 90% of the cells containing this virus carried a defective DNA that did not allow it to replicate. This means that only 10% of the cells in the reservoir had an operational DNA and provided a site for effective viral replication. It is this reservoir that is ‘competent’ for viral replication that will now be targeted in order to prevent a viral rebound following discontinuation of treatment.

Do we know where these ‘competent’ cellular reservoirs are found?

M. B.: This is extremely difficult to determine because of the scarcity of biological material available for our research. The reservoirs are extremely small in number; we are talking about one per million CD4 T-lymphocytes, the immune cells that are the principal targets of HIV. In addition, we are working almost exclusively on blood samples collected from patients, because the biopsies that would provide access to the major organs affected by viral persistence are too invasive. Indeed, we suspect that the reservoirs are cells that may be found in anatomical sanctuaries that are little accessible to antiretroviral compounds, such as secondary lymphoid organs (spleen, lymph nodes, lymphoid tissues that have accumulated in mucous membranes).

As for my team, we have succeeded in demonstrating the presence of a surface marker expressed on HIV-infected cells in patients under antiretroviral treatment. This should help us to better identify and characterise these cell reservoirs. We are therefore making gradual progress.

What about research on a future vaccine against HIV/AIDS?

M. B.: A vaccine must be a research priority, as it will enable us to put a definitive end to the AIDS epidemic. Several large-scale trials have failed during the past fifteen years, in Thailand and more recently in South Africa, but we need to maintain our efforts. The main problem we are currently facing is that while people who contract HIV/AIDS have a very good antibody response, it is still not sufficient to prevent the virus from spreading throughout the body. Indeed, this pathogen mutates extremely rapidly during its replication cycles – with one error every thousand DNA bases at each cycle, which is enormous. This means that the vaccine needs to do better than the virus itself in triggering an effective immune response by inducing very broad-spectrum neutralising antibodies.

The WHO has set 2030 as a deadline to halt the HIV epidemic. Do you think this is realistic?

M. B.: It is a laudable goal, but we know we will not attain it, for all the societal and cultural reasons mentioned at the start of our discussion. To eradicate AIDS, a giant leap forward will be necessary in vaccine research and our knowledge of the immune response. Today, people living with HIV are well, so we are not in the emergency situation of the 1980s and 1990s. For this reason, I think that the time has come for scientists to allow themselves a bit of a leeway to develop new ideas and take risks. This will imply longer-term research, which means that efforts and funding will continue to be necessary. It is important to insist on this latter point, because when you talk to some politicians, HIV no longer seems to be an issue.

- 1. Director of the molecular virology laboratory at the Institut de Génétique Humaine (CNRS / Université de Montpellier).