You are here

Prison Life Index opens a window on life in jail

What it means to live in prison remains largely ignored by the vast majority of citizens, and even more so outside of their own country. The French NGO Prison Insider1, which has provided information online since 2015 on prison life throughout the world, is now offering a synthetic view of the enforcement of rights in jail. The Prison Life Index, developed with two laboratories from France’s CNAM conservatory of arts and crafts2 and the CNRS3, has established an assessment grid for incarceration conditions with regard to the fundamental rights guaranteed by international standards, with a view to raising awareness of their violation.

“In general, the subject of detention is only brought up when an extraordinary event occurs, most often a tragic one. However, everyday prison reality remains little known,” sums up Florence Laufer, the director of Prison Insider. “The advantage of a specific indicator is that it can be understood by everyone. Yet we wanted neither an oversimplification nor a ranking, so we asked the LAMSADE laboratory to help us develop a rigorous scientific tool.”

After four years of study, the first results of the Prison Life Index were published online4, covering twelve countries or nations: South Africa, Australia, Chile, Ivory Coast, Scotland (UK), France, Georgia, Ireland, Lebanon, Norway, the Philippines, and Portugal. A multidisciplinary committee consisting of lawyers and sociologists specialising in prison life, economists, computer scientists, and representatives from Prison Insider oversaw the research. The doctoral student Lola Martin-Moro – under the aegis in particular of the computer scientist Meltem Öztürk, an academic at the LAMSADE – worked on an aggregation methodology for qualitative rather than quantitative mass data5 in order to establish a “composite indicator”.

Reliability and traceability

Developing this innovative indicator required multiple stages: designing a structure able to identify the rights being assessed; establishing the necessary data to determine their compliance or violation; and finally gathering this material. The sources came from interviews with independent experts, documentary research, and information already produced by Prison Insider, such as updated “country profiles”, which describe 380 aspects of prison life. On the basis of the primary international instruments used for detention, 61 indicators were grouped into five major groups of rights: “eating, sleeping, showering”; “medical care”; “being protected”; “being active”; “being connected.” This complex mass of information thus gave rise to a simple and universally applicable index.

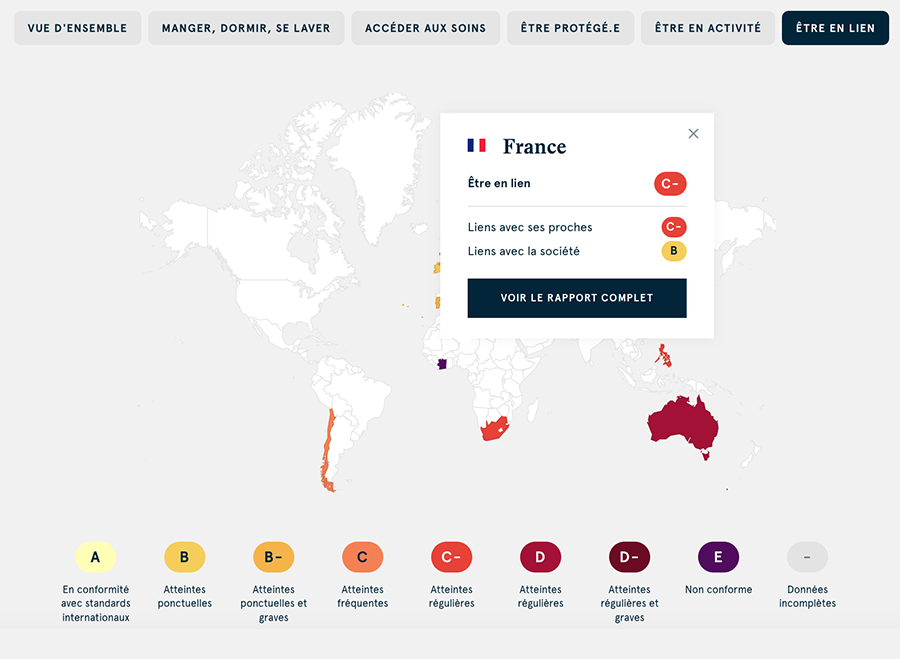

A qualitative evaluation is provided for each indicator: between A (meaning that international standards are complied with) and E (that they are systematically violated), six additional levels are proposed, with B, C, and D respectively corresponding to occasional, frequent, or regular violations. The “minus” sign following these three letters refers to the severity of the violations.

This legibility, Öztürk emphasizes, required “a tremendous amount of work”. Beyond needs in linguistic translation, the researchers had to develop their own data based on the principles of “multi-criteria decision analysis”, which guided the laboratory’s research, and helped create a robust index “that cannot be accused of distorting reality, unlike most so-called indicators that steer decision-making” .

“We also favour the use of explainable methods that ensure the reliability and traceability of our results, a token of Prison Life Index’s credibility,” concludes Öztürk, who also points out that the qualitative evaluation does include some subjectivity. In addition, the calculation is “non-compensatory”: respecting one right does not offset the violation of another. “Each of the 61 indicators corresponds to a fundamental right,” indicates Laufer, “however all standards must be applied.” As to the choice of countries or nations studied, it is partially due to a pragmatic factor: private and public funding, especially that provided by the Council of Europe.

Varying degrees of severity

What overall view do these initial results provide? As expected, none of the twelve countries evaluated fully enforces international standards. Violations have been observed in each category, with varying frequency and severity. For a single right, such as that to call loved ones, multiple reasons can explain its non-observance: restrictions, absence, faulty telephones or booths, excessive monitoring, and censorship. The comments featuring on the site offer explanations for each situation.

For example, for the right to receive visits from close relatives, Australia comes in lowest among the countries assessed, with regular violations (D). In France, this right is also subject to frequent and severe breaches (C-). Distance affects women in particular, as few prisons or quarters are reserved for female detainees. In another example, regarding the disciplinary system – which must be governed by public regulations and whose measures must be applied proportionally – evaluations are generally very concerning, with six countries between D and D- (Chile, Lebanon, South Africa, Ivory Coast, Australia, and the Philippines).

In France as well, experts have reported excessive use of isolation as a disciplinary measure. This is also true in Norway, where individuals with mental disorders can be kept in isolation, including between two stays in psychiatric hospitals. It is therefore possible to compare results relating to specific criteria in different countries, but also to see how penitentiary systems with highly unequal resources manage the same rights.

For instance, looking at France and the Ivory Coast, As – i.e. compliance with the law – are the exception in both cases. In France, while poor living conditions are well-known, “frequent and regular violations”, sometimes severe, have been highlighted for numerous fundamental rights, whether it be protection of the physical and psychological integrity of detainees, their access to medical care, to work, training, and visits, among others. Prisoners in the Ivory Coast suffer from even worse conditions (indicated by a large number of Es), and as Laufer stresses, these qualitative evaluations take the country’s general living conditions into account.

“In France, violations of the right to be properly fed correspond to meals of poor quality, sometimes served cold, and in insufficient amounts; in the Ivory Coast, detainees commonly suffer from malnutrition. In comparison, sleeping on a mat on the ground may seem acceptable, whereas in France mattresses on the floor in cells are a sign of poor housing quality. Even though human rights are universal and fundamentally have the same value everywhere, differences in the standard and norms of living are taken into account.”

Is it fair to apply the same analytical index to rich and poor countries? The director of Prison Insider believes it is, for “these international standards, including the Nelson Mandela and Bangkok Rules, were adopted by the General Assembly of the United Nations. They are not binding, but represent a political consensus in defining the fundamental rights of detained persons”.

Attempting to summarise these studies in a few lines can sometimes prove deceptive, as their interest resides in their simultaneously exhaustive and detailed nature. Each “score” is accompanied by elements of context and links to documentation. “In the world apart that are prisons, out of sight, where counterweights are weak, we would expect that in general standards are violated more often than they are enforced. However, these new indicators provide a precise and nuanced image of reality, and point to possible improvements, including for use by professionals,” Laufer adds. “The Prison Life Index also shows, and this is hardly a surprise either, that humanity and dignity are not always a question of financial resources.” She also points out that while detention involves only a small number of individuals, it represents a challenge for all citizens, since the poor treatment suffered inside sooner or later impacts the outside. If it increases the general public’s awareness of prison conditions, the Prison Life Index will have fulfilled its goal. Prison Insider hopes to assess an extra thirty countries in the coming years. ♦

Consult the Prison Life Index

- 1. https://www.prison-insider.com/en

- 2. Interdisciplinary Research Center in Action-Oriented Sciences (LIRSA).

- 3. LAMSADE (Laboratoire d'Analyse et Modélisation de Systèmes pour l'Aide à la Décision – CNRS / Université Paris Dauphine-PSL).

- 4. https://www.prison-insider.com/en/informer/prison-life-index

- 5. Work completed as part of a CIFRE thesis.