You are here

Forgotten dates in Europe’s history (1/4)

(The excerpts below are taken from the book Chroniques de l'Europe, CNRS Éditions, January 2022).

1764 - The death penalty: neither useful nor necessary

In 1764, a breath of fresh air was to sweep through the philosophy of criminal law. The young Italian Marquis Cesare Beccaria, a doctor of law and follower of the Encyclopaedists, anonymously published his Dei delitti e delle pene (On Crimes and Punishments). In this work, he defended an innovative vision of a justice system that would differentiate crime from sin, and in which the law would no longer be dictated by religion and morality, but by social utility. Beccaria opposed arbitrary decisions and set out what was to become the “principle of legality” of crimes and punishment: there can be no crime or punishment except by virtue of a precise and clear criminal law, of which the judge is merely the enforcer, the “mouth that speaks the words of the law”, as the French writer and philosopher Montesquieu put it.

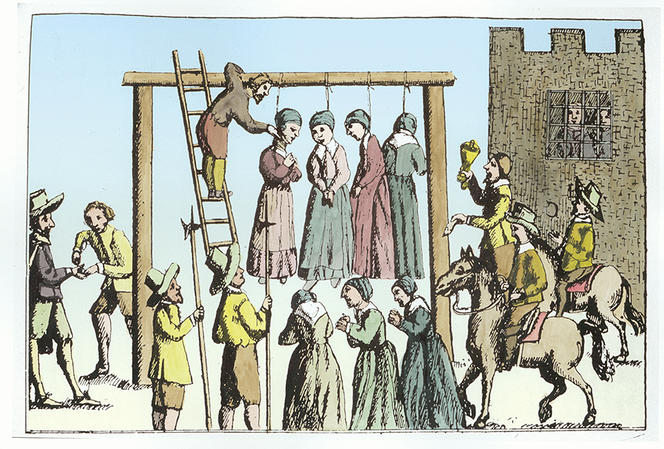

Beccaria, an ardent defender of the moderation of the law and favourable to a system that aimed to reform and reinsert the criminal, argued that the punishment should be proportional to the crime. Among other reforms, he called for an end to torture as a way of obtaining confessions, as well as the abolition of cruel treatments and the death penalty, which he considered to be both useless and barbaric. This plea challenged the foundations of a justice system based on pecuniary, ignominious and corporal punishment, and, ultimately, on the death penalty. All over Europe, the gallows and the gibbet were accepted as the ordinary fate of criminals.

Executions, which were public and theatrical, were supposed to purge society of its evildoers and were intended to be educational. Displaying and torturing the condemned in the presence of the public was a way of staging the criminal's atonement and of making an impression on onlookers that would turn them away from the temptation of crime.

The Enlightenment questioned this system which, far from acting as a deterrent, more resembled an entertaining spectacle capable of arousing the baser instincts. Moreover, it rendered any miscarriage of justice irreversible. In this context of debate, On Crimes and Punishments kindled considerable interest in Europe. Beccaria was invited to literary salons, and his book, republished three times in six months and translated into several languages, became a sort of legal guide for enlightened lawmakers. However, not all were convinced by his ideas, which, according to Kant, were the result of oversensitivity. In 1766, his most ferocious critic, the French lawyer Muyart de Vouglans, published a Refutation of the Hazardous Principles Exposed in the Treatise on Crimes and Punishments. Convinced that crime is proof of the evil that inhabits the criminal rather than the consequence of a social context, he accused the reformers of encouraging it through punishments that were overly lenient.

Although opposition to the death penalty remained in the minority, the idea gradually gained ground in political debate, championed in particular by Revolutionary figures such as Condorcet and Robespierre. The French Penal Code of 1791 abolished torture in favour of imprisonment, which was to become the norm and which Beccaria already regarded as a more effective deterrent than execution due to its duration. Although the text did not put an end to the death penalty, it drastically reduced the number of capital crimes. Capital punishment remained common in Europe until the twentieth century, since a large section of public opinion was long convinced of its pedagogical virtues. However, the nineteenth century saw the emergence of abolitionist movements following in the footsteps of Beccaria and the Enlightenment, which eventually put an end to executions in the nations of Europe, initially de facto and then de jure. In 2021, Belarus was the only remaining European country that continued to apply the death penalty.

Amandine Malivin, independent researcher

13 June, 1782 - Europe's last witch

On 13 June, 1782, a housemaid called Anna Göldi was executed in the town square of Glarus, in German-speaking Switzerland. Accused of making a pact with the devil and poisoning her masters' daughter, she was tortured, decapitated and deprived of burial. Göldi's trial caused a huge stir in Europe in the face of what appeared to be the product of a barbaric and superstitious form of justice belonging to a bygone era. The witch hunt that had raged throughout Europe for nearly three centuries was entering its final moments, and Anna Göldi was one of the last women to be sentenced to death for witchcraft.

Witch hunting, a dark side of the humanist Renaissance, originally flourished in a context of ideological rivalry between European states. It crystallised around a new definition of witchcraft based on the demonic pact and the Sabbath. Witchcraft was no longer considered a pagan heresy but rather as a plot against Christianity, with suspects serving as scapegoats for societies that were anxious to display the purity of their community. The papal bull Summis desiderantes affectibus (1484) made it a crime of divine lèse-majesté, while the Hammer of the Witches (1486) by the German Dominicans Institoris and Sprenger became the guide of choice for witch-hunting jurists and clerics.

Witch hunts frequently arose from neighbourhood disputes, crop failures, infertile livestock, or even disappearances or suspicious deaths that required a propitiatory sacrifice. Their pace mirrored religious and political crises – denominational rivalries between Catholics and Protestants, the French Wars of Religion (1562-1598) and the Thirty Years War (1618-1648) – and peaked between 1560 and 1650. The number of trials has been estimated at 100,000, leading to 50,000 executions.

The epicentre of this “Great Witch Hunt” stretched from the North Sea and the Rhine to northern Italy. Border areas, where interdenominational conflicts were rife, were the hardest hit.

Repression in France, the rest of Italy and Spain was more moderate, numbering a few thousand cases in each country, well below the 22,500 people burnt at the stake in the Holy Roman Empire, while in England, Portugal, Poland and the Austrian Empire witchcraft was only rarely punished.

Women, mostly widows or spinsters who were relatively elderly and had no family or social network to protect them, made up 60 to 80% of those accused of the crime of witchcraft. Many of those sent to the stake were healers and midwives, who possessed traditional empirical knowledge that was perceived as magical and thus came under suspicion. This gender-based persecution was a consequence of the degraded image of women caused by the Querelle des femmes, or “Woman question”, a humanist debate about their supposed natural inferiority.

Its misogynistic argument lay at the heart of all the demonological treatises. For instance, the Hammer of the Witches explained that “all witchcraft stems from carnal lust, which, in women, is insatiable”.

At the dawn of the eighteenth century, the abatement of denominational conflicts and the consolidation of the authority of modern States put an end to this persecution frenzy, in which the relegation of traditional female practices and the growth of gender inequality in European societies had reached a climax.

Clyde Plumauzille, CNRS, Roland Mounier Centre

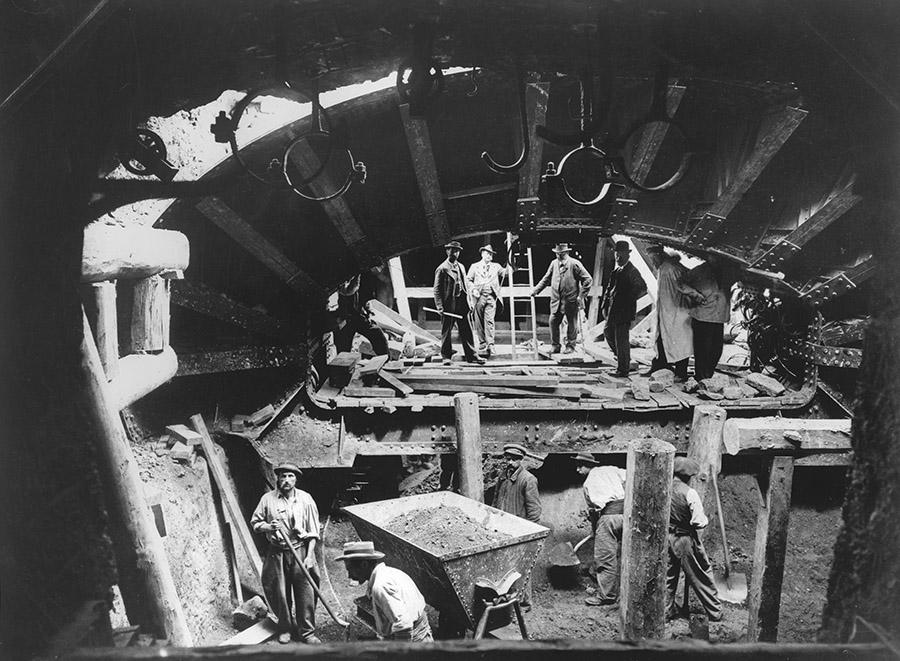

1817 - The three thirds of the worker's day

In the early nineteenth century in New Lanark, Scotland (UK), a prosperous cotton mill owner named Robert Owen was wondering how to improve the working conditions of his 4,500 employees while maintaining the productivity of his factory. After initially limiting work to ten hours, in 1817 he decided to divide the day into three equal parts: "eight hours labour, eight hours recreation, eight hours rest". This was a revolutionary idea. At the time, Britain was in the throes of industrialisation, and the use of steam engines (which required continuous maintenance), and gas lighting (which enabled work at night), meant that the working day was getting longer. In most cases, workers in spinning mills laboured non-stop for 12 or even 14 hours.

In these conditions, how could the need to work be reconciled with the basic requirements of each individual? This was the challenge facing Owen, who was not opposed to industrialisation, which he saw as a source of progress, but to its immoral management and the social divisions it engendered. While not restricting the question of workers' rights to that of working hours, he experimented with a series of reforms that intrigued Europe and drew the crowds to New Lanark. In 1818, Owen went to the Congress of Aix-la-Chapelle, then in Prussia, in an attempt to convince the heads of state gathered there. However, they paid little attention to the man today considered to be the spiritual founder of British socialism.

Despite the gradual industrialisation of the continent, campaigns for the reduction of working hours remained minimal until 1848, even though the first laws limiting the work of children and women (the Factory Acts of 1833 and 1844) were passed under the influence of the British reform movements.

And although legal and moral arguments in favour of the right to human dignity and to health gradually gained ground, the main concern was the threat of a loss of income for workers: how could they work less without earning less? Above all, the diversity of professional practices and modes of remuneration made it difficult to measure work time, which was however necessary if a single standard was to be adopted. This was eventually provided by the newly-formed International Workingmen's Association, which at its first congress in 1866 in Geneva (Switzerland) declared that “the legal limitation of the working day is a preliminary condition without which all further attempts at improvements and emancipation of the working class must prove abortive”, and proposed eight hours as the legal limit.

This demand met with strong resistance, prompting the Second International in 1889 to make every First of May a day of struggle for the eight-hour day. Throughout Europe, many conflicts broke out in its name. A number of strikes became landmarks in the history of the labour movement, whether they failed, like that of the textile workers of Crimmitschau (Germany) in 1903, or were successful, like the protest at the La Canadenca electricity plant in Barcelona (Spain), which then spread to the entire city and in April 1919 forced the Spanish government to bring in the first European legislation, after Soviet Russia, limiting the working day to eight hours.

Little by little, workers' struggles, together with legislation, brought in shorter working hours, thereby opening up the possibility of leisure time. In the aftermath of the First World War, holidays for workers, obtained either through sectoral agreements or by law, granted them access to a prolonged period (initially a week) of rest. In today’s professional environment, time – whether dedicated to work or leisure – continues to be a central cause of conflicts and negotiations.

Isabelle Matamoros, Sorbonne Université/Sirice, and Fabrice Virgili, CNRS/Sirice

Further reading

Chroniques de l'Europe (in French), coordinated by Sonia Bledniak, Isabelle Matamoros and Fabrice Virgili, CNRS Éditions, January 2022, 272 pages, €20 (available in digital format).

Explore more

Author

Chroniques de l'Europe (in French), coordinated by Sonia Bledniak, Isabelle Matamoros and Fabrice Virgili, CNRS Éditions, January 2022, 272 pages, €20 (available in digital format).