You are here

Forgotten dates in Europe's history (3/4)

(The excerpts below are taken from the book Chroniques de l'Europe, CNRS Éditions, January 2022).

1906 - Finnish women get the vote

In Finland, a Grand Duchy dependent on the Tsar of Russia, universal suffrage was introduced in 1906 after a hard-won battle, together with the creation of a modern Parliament of 200 members. On 15 and 16 March, 1907, 14 years after New Zealand, Finnish women became the first in Europe to vote in parliamentary elections.

Nineteen of the 62 female candidates were elected. Although the assembly was dissolved a year later, the measures rapidly passed under pressure from trade unions and women's organisations included a law on working hours in industrial bakeries and another banning alcoholic beverages.

At the dawn of the 20th century, there was nothing new about the call for women's suffrage, and it had already formed part of article X of Olympe de Gouges' Declaration of the Rights of Woman in 1791: “A woman has the right to be guillotined, she should also have the right to debate.” However, her voice made little impact throughout the 19th century, and even the first International Congress on Women's Rights (Paris, 1878) refused to allow Hubertine Auclert to take the floor on the issue.

It was only after the creation in 1904 of the International Woman Suffrage Alliance that European feminists made the right to vote central to their demands, backed by large-scale campaigns that were more or less radical depending on the country and the people involved. Not only did they call for the equality of all individuals, they also underlined the specific benefits that women would contribute to the life of the community, adding a touch of utopia to their arguments: “Once women vote, there will be no more wars or social evils.” Although Governments gradually began to yield, particularly after the two world wars, some attempted to postpone truly universal suffrage by allowing women to vote in local elections only, to be elected but not to cast their ballots, or vice versa, or by raising the legal age for the female vote.

After universal suffrage was introduced in Norway (1913), Denmark (1915), and the Netherlands and Russia (1917), women in many more European countries gained the vote between 1918 and 1920: in the UK (provided they were over 30 until 1928), in Germany, and in the nations resulting from the break-up of the former Empires (Austria, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, and Poland). In Belgium, except for war widows benefiting from the “suffrage of the dead”, they could only take part in municipal elections. Women were granted political rights in Spain under the Second Republic (1931-1939) in 1931, and in Kemal Atatürk's Turkey in 1934.

In France (decree of 21 April, 1944) and in Italy, they had to wait until the end of the Second World War, in Greece until 1952 and in Switzerland until 1971 (in federal elections). In Portugal, women won the right to vote in the Carnation Revolution of 1974 and in Spain, after four decades of Franco's rule, they were once more able to do so in 1977.

In 1992, the European Summit of Women in Power was held in Athens (Greece). Twenty female leaders signed the Athens Declaration for better representation of women in political assemblies and the senior public administration, a prelude to campaigns for “parity democracy”. Despite this, the term “suffragette”, which designated the radical British militants of the early 20th century, still hasn’t lost its pejorative connotation.

Françoise Thébaud, Université d’Avignon

September 1918 - A psychoanalyst's couch for all

On 28 and 29 September, 1918, the Academy of Sciences in Budapest (then in Austria-Hungary) hosted the 5th congress of the International Psychoanalytical Association (IPA) founded in 1910 in Nuremberg (Germany). All the disciples of Freud's theories flocked to the event, and gathered around the master. More surprising was the presence of military and civilian observers sent by the German and Austro-Hungarian armies and governments. Their attendance confirmed the recognition of psychoanalysis as an effective psychotherapy for the treatment of mental illnesses.

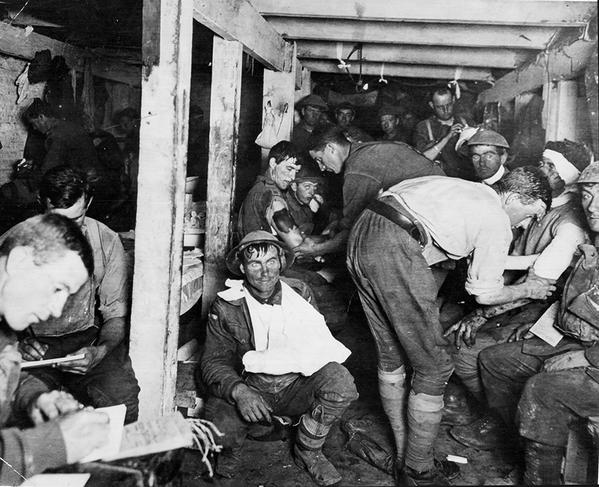

The subject was of vital importance at the time, since the mass mobilisation and violence of the battles of the First World War had led to an unprecedented increase in mental disorders. Several hundred thousand men were treated in the neuropsychiatric units of the German and French armies, while in Britain, some120,000 ex-soldiers had been pensioned off following the war. Although the military staffs had an interest in the recovery of these men in order to replenish their fighting forces, the question of the mental health of the survivors, both civilians and soldiers, had become a major concern.

The congress also marked a paradigm shift in the psychological sciences. Before 1914, psychiatrists believed that war had no direct impact on mental pathologies. Alienated soldiers were merely considered victims of their morbid antecedents or of those inherited from their forebears. They were thought to be in some way susceptible to such disorders. As for psychoses, doctors believed that events (war) contributed to delusions but were not the primary cause. Yet in Budapest, the Hungarian Sándor Ferenczi and the German Karl Abraham submitted their observations as medical officers. According to them, the source of traumas was psychological rather than the result of damage to the nervous system.

This also heralded a major departure, since psychoanalysis was now moving towards social treatment. Although Freud did not make the trauma of soldiers a central element of his thinking, he did believe that the State should take mental as much as physical health into account. In his speech, he suggested opening free dedicated clinics where practitioners would be trained in psychoanalysis. This raised the complex question of teaching the method at university. The work of the congress, published in 1919, resonated throughout Europe.

At the beginning of the conflict, Freudian theories, which were more influential in the German-speaking world, were introduced in Italy by Levi Bianchini, in France by the military psychiatrists Régis and Hesnard, and in Britain by Jones. Although in France mistrust of the German enemy's culture held back discussion, in Britain the scientist WHR Rivers drew inspiration from psychoanalysis to treat shell-shocked soldiers.

In the 1920 and 1930s, the members of the IPA put these ideas into practice: they set up training courses, sparked debate about genuine health policies, and, in collaboration with local authorities, launched plans for clinics in Vienna, Berlin, London, Budapest, Zagreb, Moscow, Frankfurt, Trieste and Paris. The Budapest congress was thus a turning point in theories of trauma and in the definition of the role that psychoanalysis assigned itself in society.

Stéphane Tison, Le Mans Université / Temos

1924 - The robots attack

Written in 1920 and published in 1921, the play R.U.R (Rossum's Universal Robots) by Karel Čapek (1890-1938), one of the greatest Czech writers of the period between the two world wars, quickly became a worldwide success. Translated into English, performed at the Garrick Theatre in New York in 1922, and in Vienna, Berlin, Warsaw, Belgrade, Budapest, London, Moscow, Brussels and Tel-Aviv, it was first staged in Hanuš Jelínek's translation at the Comédie des Champs-Élysées in Paris on 26 March 1924, under the direction of Theodore Komisarjevsky. In 2016, it was even made into an opera.

The play is a work of science fiction featuring androids devoid of feelings, who are invented by Rossum, and mass-produced by his R.U.R company. They eventually revolt and wipe out humanity, while two of them discover love, in a glimmer of biblical hope. This fable, which is at the same time a fatal prophecy, is well illustrated by the words uttered before the final drama by one of the characters, the engineer Alquist, the play's only human survivor: “We, humans, the pinnacle of life, are no longer interested in anything – neither children, nor work, nor misery! Except for one thing, of course – pleasure, enjoyment, as much of it as possible and as fast as possible! And you want to have children? Helena, what good are children to people who serve no purpose?” An imperfect humanity is thus replaced by robots who are perfectly suited to every task, who create a world without emotions, without ornamentation, where everything is just pure efficiency.

Radius, the leader of the robots, sums up the new situation: “The power of man has fallen. By gaining possession of the factory, we have become masters of everything... A new world has arisen: the Rule of the Robots.” The neologism “robot”, derived from the Czech word robota (drudgery) and invented by Josef Čapek, Karel's older brother and a versatile artist, was eventually to make its way into every 20th century dictionary.

The play is far from being the only work of science fiction written by this humanistic playwright: Krakatit (1922), Meteor (1934), War with the Newts (1936), and The White Disease (1937) take up the theme of the technological and ideological risks that threaten the world, and, a century later, some of his works continue to be very topical. Symbolically, their author died in December 1938, on the eve of the disaster of the Second World War, while his name was being mooted for the Nobel Prize in Literature.

This dystopia, the dark side of utopia, belongs to a tradition in science fiction that goes right back to the Golem (itself rooted in Prague's Hebraic tradition since the 16th century), both in literature and film, illustrated by works such as Yevgeny Zamyatin’s We, Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, George Orwell’s 1984, Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451, Pierre Boulle’s Planet of the Apes and Fritz Lang’s Metropolis. All these works of fiction questioned the assumption that scientific progress, industrialisation and Taylorism were of benefit to humans.

In R.U.R., Čapek's criticism of social and economic dehumanisation was also targeted at the authoritarian regimes embodied at the time by the Soviet system, and later on by the Nazis: part of his work attempted to alert humanity to the consequences of the processes and events taking place at the time.

Antoine Marès, Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne / Sirice

Further reading: Chroniques de l'Europe, coordinated by Sonia Bledniak, Isabelle Matamoros and Fabrice Virgili, CNRS Éditions, January 2022, 272 pages, €20 (available in digital format).

Explore more

Author

Chroniques de l'Europe (in French), coordinated by Sonia Bledniak, Isabelle Matamoros and Fabrice Virgili, CNRS Éditions, January 2022, 272 pages, €20 (available in digital format).