You are here

Cultural property on the path to restitution

From inside the wooden box in which the white-gloved porters of the musée du quai Branly-Jacques Chirac just placed him, the cavernous voice of the anthropomorphic statue of King Béhanzin, half-man half-shark, asks itself in Fongbe, the language of Benin: “Will I recognize anything, will they recognize me?” Today this statue is a number, one of the twenty-six works France is returning this year (2021) via cargo plane to the country it colonised from 1894 to 1958. The director Mati Diop, born into a French-Senegalese family, is on hand to film this first official restitution, and to accompany the works to the presidential palace in Cotonou, the country’s economic capital, where thousands of Beninese will come to discover it after 130 years of absence.

The plundering actually occurred before colonisation, from 1890 to 1892, when battles raged between the French army and King Béhanzin’s troops, one third of which consisted of female combatants known as the Agojie, whom the French called “the Amazons.” On 17 November 1892, at the order of Colonel Dodds, the French entered Abomey, the capital of the former kingdom of Dahomey (current-day Benin), where they found the royal palace burning, set on fire by Béhanzin before taking to the maquis. The soldiers seized a large number of objects, including three large royal statues and four doors that Béhanzin and his faithful had buried underground. A small portion would be given to the Ethnographic Museum of the Trocadéro six months later by Colonel Dodds, now a general; the rest would be put on the ark market.

Calls for restitution since the late nineteenth century

The restitution of works to African countries and other former colonies (Oceania in particular) is not new, with demands for return being almost as old as spoliation itself. One of the first official requests came in 1880 from Emperor Yohannes IV of Ethiopia, when he demanded the restitution of the royal collections wrested from the Fortress of Magdala in April 1868. This treasure, consisting of a crown adorned with representations of the Apostles and the four Evangelists–and stolen by a British soldier during the attack on the fortress–is given pride of place at…the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

Calls for the restitution of objects became more explicit upon independence in the 1960s. In 1970, UNESCO adopted a convention establishing the legitimacy of the return of cultural property. In 1973, the United Nations General Assembly adopted a resolution on the “prompt and free” restitution of artwork to countries that fell victim to expropriation, which will “strengthen international cooperation in as much as it constitutes just reparation for damage done.” However, this resolution was adopted with the abstention of the former colonial powers. In 1978, the Director-General of UNESCO launched a plea “for the return of an irreplaceable cultural heritage to those who created it,” and forcefully affirmed that “this is a legitimate claim.”

“In terms of the law, colonization was described as a ‘sacred trust of civilisation’ by the Covenant of the League of Nations in 1919, and is still not considered an illicit act internationally on which a principle of reparation can be based,” points out the lawyer Vincent Négri, from the Institute for Political Social Sciences.1 “International legality is founded on a rule of non-performance of international treaties, and no conventions adopted can reach back in time to the acts of dispossession against various peoples during the colonial period.”

As a result, the applicable law in France is the law of heritage. When the government of Benin demanded restitution in 2016, on the grounds that “our parents and children have never seen these cultural goods, which constitutes a handicap in the harmonious intergenerational transmission of our collective memory,” the French Minister of Foreign Affairs issued an outright refusal, couched in pure administrative language: “The property that you mention has sometimes been part of the public domain movable property of the French state for over a century, and as such is inalienable, imprescribable, and unseizable. Consequently, their restitution is not possible.”

Reasoned claims regarding history, identity, the reconstitution of heritage, and memory are opposed by an asymmetrical argument based on the law of public collections, deplores Vincent Négri. This argument has previously been accepted in only three cases: for the property despoiled from Jewish families during the Second World War, for human remains when they can be identified, and for cultural property subject to illicit trafficking.

In this context, the speech given by French President Emmanuel Macron on 28 November 2017, in the Burkina Faso capital of Ouagadougou, will go down in history. By expressing a desire for “the temporary or permanent restitution of African heritage in the next five years,” he introduced a dissonant note at the highest levels of the state. A report was subsequently commissioned from the French art historian Bénédicte Savoy and the Senegalese economist Felwine Sarr, who provided an overview of spoliation, and proposed an agenda for restitution, affirming that numerous types of African cultural property can call for legitimate restitution: “War booty and punitive missions; collection by ethnological missions and scientific ‘raids’ funded by public institutions; objects originating from such operations, passing through private hands, and gifted to museums by the heirs of officers or colonial civil servants; and finally objects originating from illicit trafficking after independence.”

Twenty-six works returned: a first small step by France

Art dealers and certain museum curators are trembling, as the (stormy) debate has been revived across Europe. France, however, is moving backward after this major step forward, for it has not committed to a framework law—instead passing a “law of exception” in 2020—to return twenty-six articles of cultural property (chosen by France) to the Republic of Benin, and a single article to the Republic of Senegal (the sabre said to have belonged to El Hadj Omar Tall, the Toucouleur military commander who died in 1864). Just twenty-six out of the thousands conserved in France is not much! Especially given that the Beninese did not have a say in the choice of objects restituted, despite their repeated requests for the return of the god Gou, exhibited in the Pavillon des Sessions at the Louvre. “We must continue to wait for a shift from the ‘legitimacy of return’ to a universal principle of ‘legality of restitution,’” comments Négri. The mentality is nevertheless changing, and numerous research programmes and networks have emerged to identify, map, and document African cultural property held by Western museums. In France, the CNRS Senior Researcher and historian of African art Claire Bosc-Tiessé, a specialist on Christian Ethiopia from the thirteenth to the eighteenth century, preceded the movement by requesting to be seconded to the French National Art History Institute in 2007 to begin amassing an inventory of African collections conserved in French museums.

With the participation of the musée d’Angoulême, the map entitled The World In A Museum: Collections of Objects from Africa and Oceania in French Museums, is now available online.2 In addition to the inventory, she is also gathering “elements for future research regarding the constitution of collections and the processes involved in acquisitions, by indicating the relevant archives (former inventories, travelogues of those who acquired the works, etc.), and by listing, whenever possible, donors and sellers,” points out Bosc-Tiessé. “In 2021 we identified nearly 230 museums in France possessing African objects, and 129 objects from Oceania. There is cultural property from Benin at the musée du quai Branly, but also at sixty other French museums!”

All in all, Bosc-Tiessé estimates there are approximately 150,000 items of African cultural property in French museums (compared to the 121 million objects they contain), of which 70,000 are at the musée du quai Branly. All you have to do is move your mouse over the map of France to find treasures conserved in little-known locations.

This property is sometimes not even exhibited, such as those in this small museum located at Poligny (4,000 inhabitants) in the Jura, which has long remained closed to the public: paddles from Polynesia, a small mesh bag from New Caledonia, a necklace of teeth from marine mammals from the Marquesas Islands, a male ear ornament made of ivory (from a whale?, asks the label), and a six-spout oil lamp from Algeria are listed on the website for these exhibition rooms that are now only virtual. Here once again we have an inventory à la Jacques Prévert, which simply lists the items without specifying whether they were bought or stolen, only that they are scattered across the four corners of France.

“Reconstructing the history of these objects entails providing an account of both colonisation and the constitution of museums in France in the late nineteenth century.” The Ethnographical Museum of the Trocadéro (today the musée de l’Homme) sent many of its duplicate pieces to the provinces. What is more, private individuals were often happy, especially at the end of their lives, to gift to their hometown museum the objects they had bought, stolen, or received as a gift during their professional life, whether they were missionaries, doctors, teachers, civil servants, or members of the military in the colonies.

In Allex, a village of 2,500 inhabitants in the Drôme department, it was the missionaries of the Congregation of the Holy Spirit that brought back numerous objects from their evangelisation missions in the nineteenth century in Gabon, Congo-Brazzaville, and Congo-Kinshasa. These include amulets and guardian effigies from the reliquary of the Fang people in Gabon, anthropomorphic statuettes from the Bembe people in the Congo, and a proverb pot lid from the Hoyo people in Angola, among others. All of this cultural property bearing witness to the daily life, traditions, and beliefs of African populations has just found a space in a brand new local museum opened in 2018. “While the principle of restitution garners unanimous support in Africa, the actual return of property sometimes prompts reluctance in the countries involved,” points out the anthropologist Saskia Cousin, who leads the ReTours3 and Matrimoines/Rematriation4 multidisciplinary research programmes, each including approximately twenty researchers, artists, and international cultural operators.

From “restitution” to “return”

“The first reason for reluctance, driven by Western art dealers and curators, is to say that Africa does not possess institutions capable of conserving its collections and combatting illegal trafficking.” The opening and construction of museums across the continent are so many responses to these criticisms. Four museums are being built in Benin alone! “The second problem involves the cost of this return,” Cousin continues. “The museums are being constructed with borrowed means, contracted primarily with France. That is why the countries involved would like to develop tourism, especially with their diaspora. The third problem relates to the future of this property. In short, should it return to a temple or a museum? This is a question of sovereignty that concerns the countries of return, and the issues are more complicated than French polemics suggest.”

On the one hand, a return to sacred spaces does not mean the public is prohibited, and the French vision of a museum empty of all vitality and sacredness is far from being universal. “While the twenty-six objects restituted to Benin bear the title ‘Royal Treasures of Benin,’ an expression borrowed from the art world, and are exhibited behind glass boxes according to thoroughly Western criteria, numerous Beninese, and the princesses of Abomey in particular, came to honour them through gestures and song.”

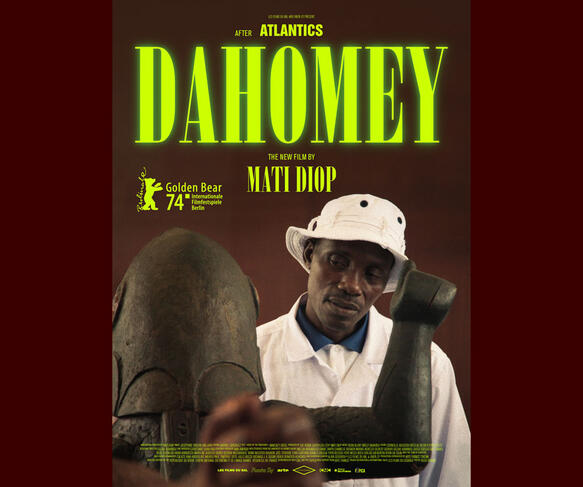

In the film Dahomey, we see the artist Didier Donatien Alihonou–who appears on the film poster–conversing with the King and ancestor Gbéhanzin. Like for many others, for him these statues are not just material goods, they embody a returned heritage, the force of return, with which it is finally possible to reconnect. “We must stop conceiving this question of return exclusively as an arbitration between countries formulating a request for restitution and states responding favourably or not,” Bosc-Tiessé affirms. “It is incidentally symptomatic that on the governmental level, this subject is handled by the Ministries for Culture and Foreign Affairs, while research and teaching are left out of a debate rarely approached from a scientific angle. It is nevertheless desirable to seek out researchers, in order to provide an account of how these works arrived in France, of the poorly understood violence involved in their capture, and to thereby write this hidden history of colonization, doing so in all its complexity.”

“It is also time to shift this issue from one of ‘restitution’ to one of ‘return,’ by taking into account the perspective of the populations and states of origin. In connection with the ReTours and Matrimoines/Rematriations programmes, we are working with researchers from Benin, Cameroon, Mali, Togo, Senegal, and their respective diasporas, and doing so based on methods inspired by collaborative anthropology. For example, for Benin, memory is essentially transmitted by ‘heiresses,’ women who inherit knowledge. We meet them and show them photos or drawings of statues and amulets whose names and uses they know, along with their associated panegyrics (speech in praise of certain persons). This memory remains extremely vivid among non-French-speaking women.”

As part of the ReTours programme, a charter5 was developed to consider traditional museums and conservation spaces as complementary, legitimate, and non-exclusive. The goal is to simultaneously have the expertise of heiresses recognized, and to facilitate the access of colleagues from the Global South to the resources needed for their studies, including in countries in the Global North, with respect to property on display, in reserves, inventories, work files, oral sources, etc. “Belgian, Dutch, and German museums are very open to welcoming and integrating the diaspora, researchers, and heirs involved; it’s much more complicated in France, where museums want to control the narratives surrounding their collections” observes the anthropologist Cousin.

A European debate

The question of restitution involves all European countries. While in England the British Museum is the most reluctant, the Cambridge, Oxford, and Manchester University museums have returned or are preparing to return works. In Belgium, a complete inventory was completed for artwork from the Congo held by the Royal Museum for Central Africa in Tervuren. The Germans have also largely begun this undertaking. Felicity Bodenstein, an art history researcher at the Centre André Chastel,6 is behind the Digital Benin project,7 which documents the artwork pillaged from the former kingdom of Benin (current-day Nigeria, not to be confused with current-day Benin, formerly Dahomey).

These works were originally seized by the British army during a punitive expedition conducted by 1,800 men in February 1897. At the time, the soldiers took the capital of Edo (today Benin City) after heavy losses, and gained possession of–in organized or individual fashion–the treasure of Oba (the sovereign).

Over 5,000 Benin Bronzes were dispersed and partly lost, including the brass relief plaques produced between the mid-16th and mid-17th century. These representations of individuals, symbols, and courtly scenes ended up on the art market, and were mostly dispersed across 136 museums in twenty countries, especially England and Germany.

“Unlike France, which devoted little money to this purpose, the Germans and English had an actual purchasing policy at the time for such objects for their museums,” explains Felicity Bodenstein. “What is more, in the late nineteenth century, each city of some note in Germany created its own ethnography museum to present itself as cosmopolitan and open toward the world, notably in hopes of being designated as the country’s capital.8That is how Germany ended up with ten times as many African objects as France, which was present much longer on the continent with its colonies.” The goal of the Digital Benin website–created by a team of a dozen individuals, and funded in partnership with the World Cultures and Arts Museum in Hamburg and the Siemens Foundation–is to gather data for the more than 5,000 objects it has inventoried, and to return them to a local culture, doing so in an engaging manner that combines both still and moving audiovisual archives. Part of the site, especially the classification of objects, is in the Edo language, the vernacular language of the kingdom where they were created and pillaged.

Beyond this exemplary site, what is the general direction of German policy for the restitution of works? “The German approach is very different from the French,” points out Bodenstein, who began her career as a researcher in that country, alongside Bénédicte Savoy at the Technical University Berlin. “The importance of the collections they possess, in addition to the very sensitive issues of memory connected to the Second World War, have made provenance a much more political and combustible topic than elsewhere in Europe.” In 2021, a national restitution agreement was concluded with Nigeria, and it is now up to each museum to develop its own agreement, in accordance with the principles of the federal government. Museums have already physically sent a few hundred works to Nigeria.

“However, all communities of origin, and in any event this is the case for Benin, do not necessarily want to recover all of their works. They want to reestablish ownership in particular, and to be involved in the cultural and political discourse that accompanies their heritage.” During the discussions surround the opening in central Berlin of the Humboldt Forum, an immense museum designed to exhibit a significant portion of this collection of Benin bronzes, an intense debate laid the groundwork for a new way forward. The exhibition space for these objects is today being co-managed by researchers and museographers from Benin City. All of the works from Benin City that were identified were first officially returned to Nigeria, which now loans them to Germany, with a small label affixed to exhibition cases signalling this process.

In Germany, a major collective study conducted jointly by Dschang University and the Technical University Berlin between 2020 and 2023, named Inversed Provenance,9 took stock of the pillaging of Cameroonian heritage during the colonial period, namely the 40,000 objects that make Germany the world’s largest possessor of Cameroonian works! “In contemporary Germany there is a ‘ghost Cameroon’–to echo the title of Michel Leiris’s famous anticolonial book, Ghost Africa (1934),” explain the authors of the study, among them Bénédicte Savoy. “Despite their invisible presence (in Germany) and their forgotten absence (in Cameroon), these collections, which in terms of quality are the world’s oldest and most varied, continue to have an effect on the societies that keep them or lost them.” The objective of the study is to analyse and publish new sources that can confirm this massive presence, and to also reach out to the communities in Cameroon that were deprived of important material items of their respective cultures, as well as to identify, as far as possible, the effects produced by this prolonged absence of heritage.

The film Dahomey ends with a debate organized by the director between Beninese students regarding this first French retrocession. A first step, or an insult to the people given the small number of objects returned? “A space had to be created for this youth, one that allows it to make this restitution part of its own history, to reappropriate it,” Diop explains. “How should a country that had to move forward and come to terms with the absence of these ancestors react to their return? How to measure the loss of that which we did not know was lost?” While waiting for a French law that is continually delayed, the figures in Dahomey emphasize the urgency of providing a response to this request for restitution issued by an entire continent

- 1. Unité CNRS/ENS Paris-Saclay/Université Paris-Nanterre.

- 2. https://monde-en-musee.inha.fr/

- 3. https://retours.hypotheses.org

- 4. The Matrimoines/Rematriation research programme focuses on the living knowledge and African matrimony both familiar and little-known (cooking utensils, musical instruments, popular objects of worship, etc.) that arrived in Germany and France, notably during the colonial period. The goal is to give voice, to “rematriate,” with a view to recognizing this knowledge and this property. For more information visit: https://cmb.hu-berlin.de/fr/la-recherche/translate-to-francais-fonds-de-...

- 5. The Porto Novo Charter https://retours.hypotheses.org/371

- 6. Unité CNRS/Ministère de la Culture/Sorbonne Université.

- 7. https://digitalbenin.org

- 8. Neither the constitution of 1871 nor that of 1919 formally specified the capital for the German Empire.

- 9. The study is now available under the name the Atlas of Absence (in English and German): https://depositonce.tu-berlin.de/items/96edf966-0bec-4c16-9e10-2b9894f097b7