You are here

Forgotten dates in Europe's history (4/4)

(The excerpts below are taken from the book Chroniques de l'Europe, CNRS Éditions, January 2022).

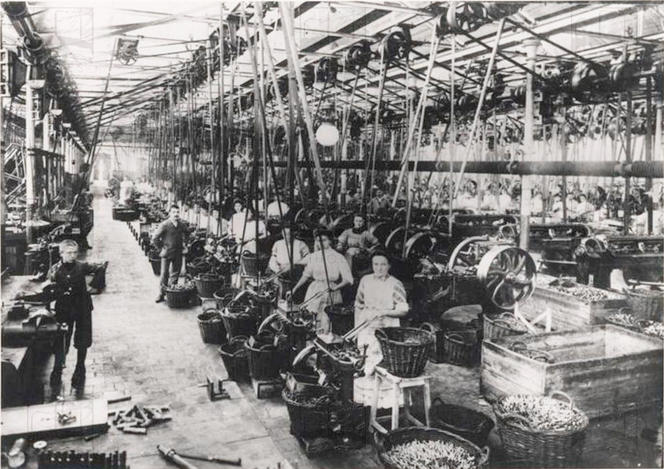

16 February 1966 - Equal pay for equal work

On 16 February, 1966, 3,000 women workers at the FN Herstal national military weapons factory, in Belgium, walked out without notice to demand the application of the principle of “equal pay for equal work”. The strikers spontaneously took to the streets, chanting their slogans. Although there was nothing new about these demands, the FN strike was nonetheless exceptional due to its length (12 weeks), its scale (almost 5,000 workers were laid off), and above all its recourse to Article 119 of the Treaty of Rome (1957), which was supposed to have made equal pay effective throughout the EEC by 1962.

In the past, there had been other actions to improve working conditions in industrial sectors employing a predominantly female workforce: strikes by match workers in Jönköping (Sweden) and in London (UK) in the 1880s are widely regarded as the first predominantly involving women. But the machine-tool operators' strike at Herstal stands out as being the first female social movement in Europe, and it soon expanded to include other demands. As a public expression of women's refusal to accept a subordinate position in society, the strike broke free from the constraints of male-dominated trade unionism and called for gender equality.

The protest, conducted with unwavering determination and soon backed by supporters of the decriminalisation of abortion, rapidly attracted attention in all the EEC member countries. With the press taking up the story in March, there were increasing expressions of solidarity, while delegations from trade unions and women's and feminist organisations in France, Italy and the Netherlands came to provide their support. In 1966, the First of May Labour Day demonstrations took place against the backdrop of a Europe-wide women's strike.

Alerted by its Economic and Social Committee, an extraordinary session of the European Parliament held in Strasbourg (France) voted on 29 June 1966 for the immediate application of Article 119. Meanwhile, the European Commission sponsored extensive surveys about the status of women workers in Europe, for the first time covering every aspect of their daily lives, including wages, working conditions, vocational training, work-family balance, and social security.

The surveys led to a first set of directives, while the Belgian lawyer Éliane Vogel-Polsky brought the issue of wage inequalities before the European Court of Justice, which in 1976 ruled in favour of the direct application of Article 119 in all the Member States. As for trade unions, they could no longer ignore the issue of the place of women in their organisations.

These changes, brought about in large part by the FN strike and its after-effects, thus sparked a genuine process in the European Community, making it a key driver in public policies on gender equality, a pioneering position that is nonetheless receding in the 21st century. Due to its many facets, the Herstal strike became a showcase for women's social struggles in Europe. Commemorated every year until 1977, and then sporadically until 2016, it remains the symbol of European women's solidarity, preserved for posterity by various media and documentary films of a rare intensity.

Éliane Gubin, Free University of Brussels (Belgium)

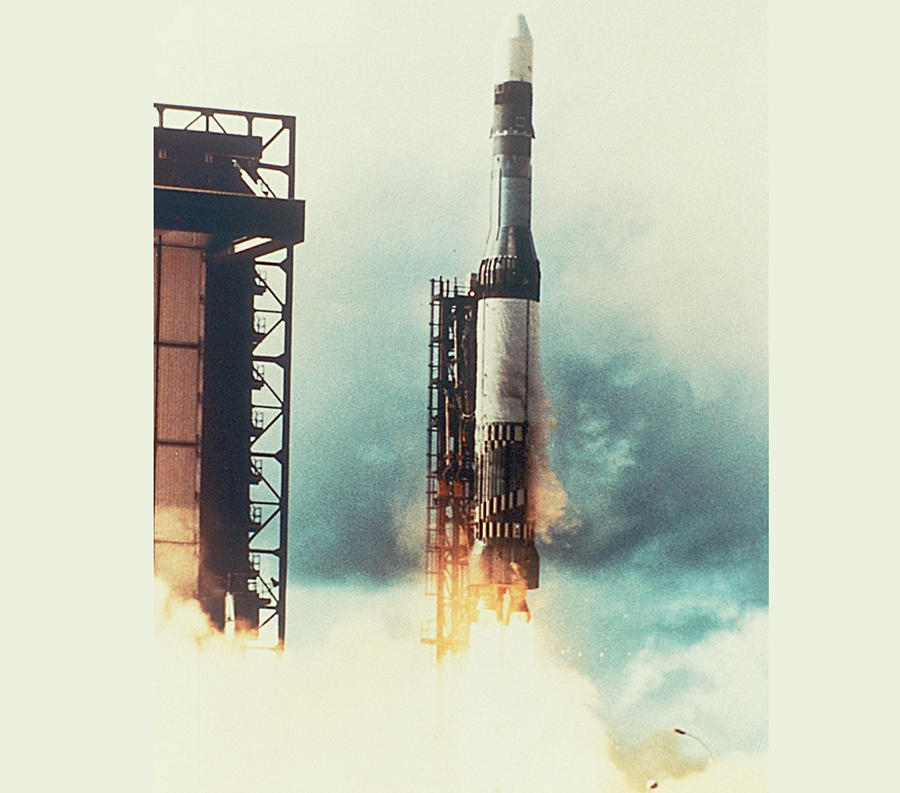

5 November 1971 - Europa, Ariane's distant ancestor

On 5 November 1971, the Europa II rocket blasted off from a launch pad in Kourou, French Guiana, boosting the hopes of its designers for independent access to geostationary orbits, so vital to telecommunications satellites. The objective of Britain, which provided the first stage of the rocket developed from its Blue Streak missile, France, which designed the second stage, Coralie, and West Germany, which with its third stage Astris was responsible for the launcher's inertial guidance, was to avoid the need to rely on the space resources of other nations.

Working with them were three other countries whose contributions, although on a smaller scale, were also indicative of a Europe-wide undertaking that transcended mere national ambitions: Italy was in charge of developing experimental satellites, Belgium provided a radio guidance station, and the Netherlands handled telemetry operations.

Only 150 seconds after lift-off however, the rocket started to go off course, the engines failed, and to the engineers’ dismay, Europa II blew up and crashed into the Atlantic Ocean, a few hundred kilometres off the coast of French Guiana. The disappointment was crushing: this was the sixth consecutive failure in the Europa programme since the signing of the Convention setting up the body entrusted with its development, ELDO, in 1962.

Initially bringing together six Western European countries together with Australia, ELDO's role was to coordinate Europe's first attempt at cooperation in the field of advanced space technologies, with the aim of producing an autonomous launch vehicle based on a joint French-British proposal. At the same time, its sister organisation, ESRO, was enjoying more success in coordinating basic research and the joint development of satellites. Things were more complicated for ELDO: due to a lack of balanced funding and sufficient leadership capacity, the project struggled to get off the ground, suffering from a host of technical failures and a gradual loss of British support under the first Wilson government.

The explosion of Europa II hastened ELDO's demise, even though a new version of the rocket was being prepared with a view to placing the Franco-German telecommunications satellite Symphonie in orbit by the end of 1973. Europe was thus forced to rely on other countries’ facilities to launch its satellites, which placed it in a state of dependency deemed unacceptable, especially by France.

The creation of the European Space Agency four years later, in 1975, finally addressed this crisis by bringing together scientific and launcher activities under one roof, thus strengthening institutional and industrial integration in pursuit of a concerted, coherent space policy. A new principle emerged on this occasion, that of the package deal, which made it possible to find efficient institutional solutions to any political disagreement between Member States: for instance, France's wish for autonomy was combined with Germany's support for participation in the US post-Apollo programme as well as the UK's desire to develop a maritime telecommunications satellite.

This marked the beginning of the story of Europe's Ariane launcher, born from the ashes of the Europa II thanks to a reinforced institutionalisation of the European space endeavour and the hard-won acceptance of France's conception of the central role played by strategic independence.

Anne de Floris, Sorbonne Université / Sirice

August 1991 - The European web opens up to the world

In early 1991, two researchers at the European Organisation for Nuclear Research (CERN), Tim Berners-Lee and Robert Cailliau, presented their colleagues with a brand-new system for sharing information between computers. On 6 August 1991 this was opened up to users outside CERN: the World Wide Web was born.

Although Berners-Lee's initial project, entitled “Information Management: a Proposal” hadn't met with the approval of his superiors, the young 34-year-old physicist had nonetheless continued to believe in his idea and, with Cailliau's help, pursued its development. Their aim was to make information stored on computers in the various CERN sites across Europe accessible in a simple and practical way, without the need to exchange messages or transmit data.

To make it possible to remotely view and access all the intelligence stored on computers connected to one another through the Internet, the two researchers designed software called Hypertext Markup Language, or HTML, able to create documents with links; they defined the transfer procedure, known as Hypertext Transfer Protocol, or HTTP; and established the addressing principle for websites, the Uniform Resource Locator (URL). A milestone was reached in November 1990, when they conceived the first server program, software that hosts pages on a computer while allowing others to access them.

As soon as the Web opened in the summer of 1991, its designers lost control of it. The Internet, which connected computers from different manufacturers by using public protocols, was much more developed in the US – which had recognised its huge potential, especially for business – than in Europe. On the East Coast, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) was particularly active. Aided by the vitality of US businesses and their central role in developing the ARPANET from the late 1960s, and then the Internet, which linked ARPANET to other data networks, MIT rapidly shifted the Web's centre of gravity to North America.

In 1991, business operations were accepted on the network, which was run by the US public research funding agency, the National Science Foundation. In 1993, the first World Wide Web developers' conference was held at MIT. This formed the basis of the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C), which went on to manage the development of the Web, and whose European pillar was the French National Institute for Research in Digital Science and Technology (INRIA).

On 6 April 1993, with some two million people already connected to the Internet, CERN decided to relinquish its rights to the World Wide Web, whose growth was exponential, driven by commercial rather than scientific needs. The first Internet browser, Mosaic, was developed at the National Center for Supercomputing Applications (NCSA) at the University of Illinois (US), subsequently giving rise to a commercial version, Navigator, developed by Netscape. The Yahoo directory was launched in 1994. The following year, Jeff Bezos, a Princeton graduate, founded Amazon. The first widely-used search engine, AltaVista, was released in November. Across the Atlantic, the future of a truly global mass medium was beginning to take shape.

Pascal Griset, Sorbonne Université / Sirice

Explore more

Author

Chroniques de l'Europe (in French), coordinated by Sonia Bledniak, Isabelle Matamoros and Fabrice Virgili, CNRS Éditions, January 2022, 272 pages, €20 (available in digital format).