You are here

Understanding society’s reactions to terrorism

You have just released a book entitled Face aux Attentats (‘In the Face of Attacks’), published by Presses Universitaires de France. What was the objective of this joint project, which you coordinated with the political scientist Florence Faucher?

Gérôme Truc:1 The book unites a body of work in the human and social sciences concerning the terrorist attacks of 2015 and 2016, some conducted as part of a call for proposals funded by the CNRS. These studies focus on previously unexplored aspects, such as the event in and of itself, as well as its psychological, social and political impact. As it happens, the collaboration of sociologists, political scientists, psychologists and media specialists is essential to fully understand all the repercussions of a terrorist attack and the way a society reacts to it. That’s the purpose of this slim volume, written for a wide audience.

Five years after those tragic events, what conclusions can be drawn from their impact on French society, based on this original research work?

G. T.: The findings challenge many preconceived notions, such as the idea that a terrorist attack only affects the citizens of the country targeted. In reality, the sociological process is more complex, and triggers many other factors. There is also the deeply rooted belief that Islamist attacks always play into the hands of the extreme right, which is far from being that obvious and systematic. The conclusions of the studies compiled in Face aux Attentats present a more subtle overview.

This is also what Guillaume Dezecache, a researcher at the LAPSCO2, demonstrates in his work on the survivors of the Bataclan attack. What are the specific findings of his study on the behaviour of people who find themselves directly confronted with terrorism?

G. T.: The study questions a widely held belief, namely that in the face of immediate danger, human beings, who are selfish by nature, can only think of their own survival – ‘every man for himself’. Actually, most of the Bataclan survivors interviewed by Guillaume Dezecache and his colleagues reported that, on the contrary, they had offered or witnessed cooperation or mutual assistance during the attack. Instead of playing dead to avoid being shot, some took the risk of comforting others, for example by holding the hand of an injured person lying next to them. These behaviours are meaningful in terms of survival strategy. In certain circumstances, it is in our better interests to be supportive and cooperate rather than act selfishly to stay alive.

Do repeated Islamist terrorist attacks like those we have witnessed in the past few years exacerbate the divisions within French society?

G. T.: The American sociologist Randall Collins has shown that while a terrorist attack sparks a reflex of solidarity in society, it also stirs up tensions. These are two sides of the same process. Consequently, repeated attacks at close intervals are problematic for national unity. This is clearly demonstrated in the study by Laurie Boussaguet and Florence Faucher on the way the French executive managed the successive crises, in January and November 2015, followed by the Nice attack in July 2016. At first there was a kind of sacred unity, culminating in the ‘March for the Republic’ on 11 January, which gradually weakened as the attacks continued. Still, the executive plays a crucial role in these circumstances because, beyond security considerations, it also needs to embody national cohesion in order to keep social divisions at bay. This was again the case when Samuel Paty was assassinated. In the midst of the outcry on the social networks, with the extreme right immediately and zealously trying to capitalise on the tragedy, the president went to the scene of the attack that same evening to deliver a plea for unity. His action helped to ‘set the tone’, which is essential in the subsequent phases of the social reaction to the attack.

The book also discusses the coverage of the attacks. What role do the media play in the way we apprehend such events?

G. T.: They play an essential role! Except for the direct victims and witnesses, what we react to in the case of a terrorist attack is the perception we get from the media. The images we are shown and the terms used to describe the event and piece together the narrative condition our reaction to it. It has been established that since the 1990s the coverage of terrorist attacks by Western media tends to put increasing emphasis on the victims and the reactions of civil society. Here again, this was quite obvious after the assassination of Samuel Paty. A great many articles in the press reported the reactions of his colleagues and students at the school where he taught, as well as of residents of the neighbourhood and other history-geography teachers. This way of dealing with the attacks puts the media in an ambivalent position, reporting on collective emotions and at the same time fuelling them.

In one chapter of your book, Claire Sécail and Pierre Lefébure examine a different facet of the media’s handling of terrorist acts, namely live television coverage. What does their research show?

G. T.: Since 11 September, 2001, in the US, and the proliferation of 24-hour news networks, the live monitoring of terrorist attacks has become the norm on television. But “hot” coverage of such events is prone to misjudgements, as in the hostage crisis at the Hyper Cacher supermarket in January 2015, when BFM TV revealed that people were hiding in the cold storage room. Or on the evening of the Nice attack on 14 July, 2016, when France Télevisions interviewed a man standing next to his wife’s corpse. Such ethical breaches cause the French media regulatory authority (CSA) to step in and are the subject of much debate within the profession. And yet, as verified by Claire Sécail and Pierre Lefébure, there is little chance of putting an end to such missteps, nor of seeing ‘good practice’ widely adopted among the media. The problem has to do with structural factors, like the division of labour within the editorial teams, the conditions specific to live coverage and the high turnover in journalism careers, which does not facilitate the transmission of know-how.

In the days following an Islamist terrorist attack, some media also promote the idea that these attacks play into the hands of the extreme right. How does this stance influence society?

G. T.: This is one of the misconceptions that I mentioned earlier. Islamist terrorist attacks offer what in political science is called a ‘window of opportunity’ for promoters of the extreme right to further their views. At the same time, some all-news channels fill their air time at low cost by broadcasting debates for which they need guests with hard-and-fast ideas and simplistic positions. Their goal is never to offer multifaceted analyses, but to encourage disputes that will arouse indignation and generate online buzz. This creates an ecosystem that is extremely hospitable to extremes. In this way, as Christopher Bail concludes in the case of the US since 11 September, positions held by a tiny minority of the population tend to be spotlighted in the media.3

At the same time, as Vincent Tiberj points out in the last chapter of the book, tolerance has been increasing in France since the 1990s. In fact, our society tends to become more and more open. This is a groundswell dynamic, rooted in the renewal of generations and apparently unaffected by the attacks. As a consequence, the French as a whole do not conflate terrorists with the overall Muslim population. It is worthy of note that there are no anti-Muslim riots in our country today analogous to the anti-Italian riots in reaction to the anarchist attacks – for example, the assassination of president Sadi Carnot – in the late 19th century. Society has, most fortunately, evolved since then.

The findings presented in Face aux Attentats include the conclusions of the REAT4 project, which you coordinated. What was your approach for conducting this research aimed at analysing the impact of terrorist attacks on French society?

G. T.: The project comprises several sections. The main one consists in analysing the content of the messages left in the spontaneous memorials at the sites of the attacks of 13 November, 2015, which were collected by the Paris municipal archives. It reveals that, from a social point of view, the reactions to such an event are not limited to a feeling of collective belonging but rather of kinship with the victims, everyone being more or less concerned. National belonging is only one factor among others, which include for example the fact of being familiar with the location of the attacks, of living or having lived nearby or in the city concerned, of knowing or not knowing people there, of being the same age or having the same sociological profile as the victims, etc. Some reacted to 13 November as rock music fans, parents or Muslims, and not merely as French citizens.

Rather than a society that responds to the attack ‘as one’, what we see taking shape is a plurality of social groups affected for various reasons, who together form a community of mourners with ill-defined borders. This is also what Romain Badouard demonstrates in his chapter devoted to social networks. After a terrorist attack, these become an arena of discussion that reveals conflicting values within society, possibly leading to the formation of counterpublics. Considering all of this, we must admit that French society today is much more pluralistic than we would like to think, although this does not necessarily imply that the social fabric is fraying.

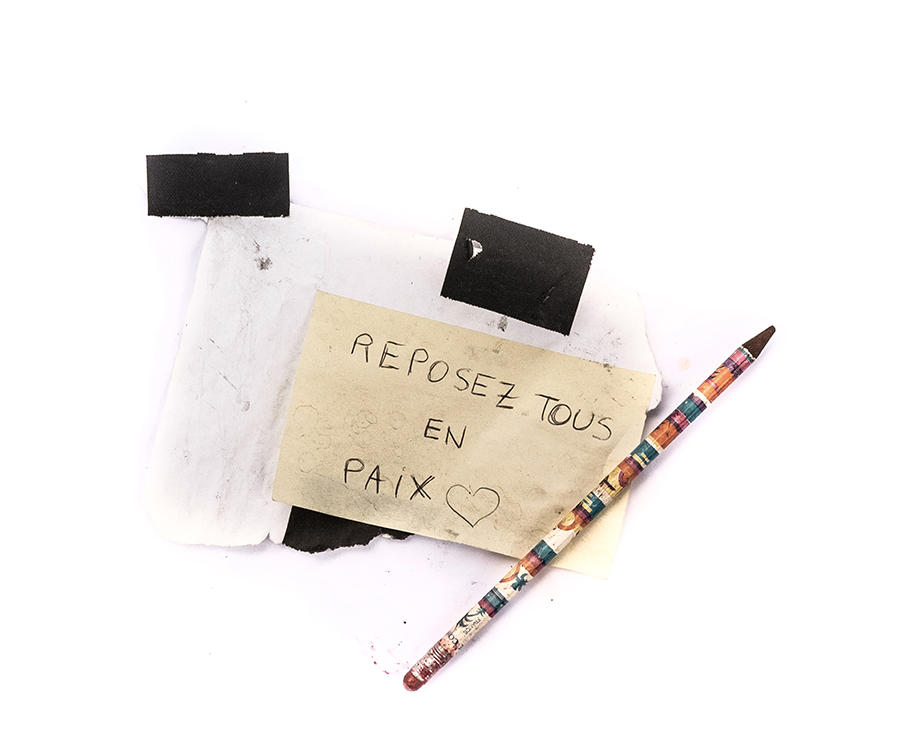

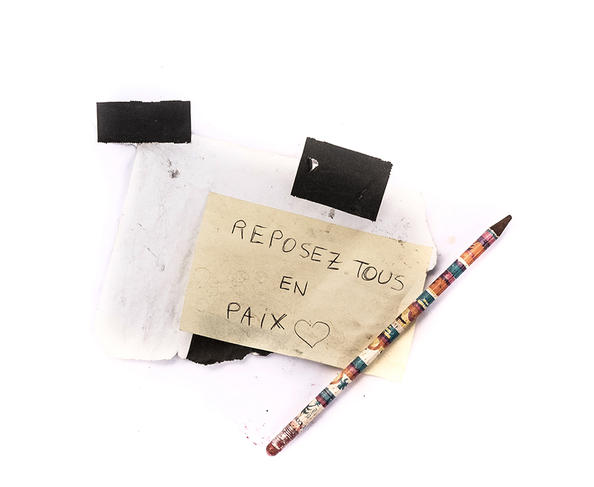

This part of your work has resulted in the publication of another book, entitled Les Mémoriaux du 13 Novembre (‘The Memorials of November 13’6), a project co-directed with the sociologist Sarah Gensburger. How did the idea come about to compile a study presenting – and at the same time analysing – the anonymous tributes to the victims of these attacks?

G. T.: The idea arose from a project in which I participated while preparing my thesis: El Archivo del Duelo, conducted by researchers from the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC), the equivalent in Spain of the CNRS, after the terrorist attacks that struck Madrid on 11 March, 2004. But we went even further, combining an analysis of the content collected from the memorials with an on-site study of the shrines and their publics. In parallel, we reflected on how they could be used for future generations. To complete this book, the only one of its kind, illustrated with more than 400 photographs, we worked closely with the Archives de Paris. One chapter is also devoted to the condolence books opened by the city hall of the 11th district after the attacks, which the historian Hélène Frouard studied as part of a specific project, also funded by the CNRS. It is a source of utmost importance for understanding the impact of the event on a more local but no less essential scale.

- 1. Face aux Attentats, Florence Faucher and Gérome Truc (directors). PUF, “La Vie des Idées” collection. https://www.puf.com/content/Face_aux_attentats

- 2. Laboratoire de Psychologie Sociale et Cognitive (CNRS / Université Clermont Auvergne).

- 3. Terrified. How anti-Muslim fringe organizations became mainstream, Princeton University Press, 2015.

- 4. La Réaction sociale aux attentats: sociographie, archives et mémoire: https://reat.hypotheses.org/le-projet-reat

Explore more

Author

After first studying biology, Grégory Fléchet graduated with a master of science journalism. His areas of interest include ecology, the environment and health. From Saint-Etienne, he moved to Paris in 2007, where he now works as a freelance journalist.