You are here

"Memory is a cardinal value of modern democratic societies"

Sadly, terrorism is now part of our lives, permeating and shaping society. How can this ‘total social fact’ be defined, given that a terrorist act constitutes a tragedy for the entire community?

Henry Rousso:1There is no international legal definition of terrorism, due to the disagreements among United Nations member countries on the subject. Indeed, the diversity of the goals, ideologies and targets of the organisations described as ‘terrorist’ (a label that most of them disclaim, whether rightly or wrongly), these entities’ different operating modes, and the multiple political, social and religious contexts in which they operate all make it difficult to arrive at a universal definition of a constantly-evolving phenomenon.

Nonetheless, most terrorist acts have certain criteria in common, starting with deliberate recourse to a form of extreme violence inducing disproportionate effects and resulting in the destruction of lives and infrastructure. Similarly, terrorism – a term synonymous with the rejection of national and international laws in the name of an alternative ‘legitimacy’ – most often aims to intimidate or disrupt a system in place (a government, a society, a human or political group) in an effort to force it to acknowledge certain claims, or even to destroy it. Such a brutal, unpredictable event, triggered by usually clandestine organised groups (even though the act itself can be a ‘lone wolf’ attack), also seeks to impact public opinion and incite collective fear.

One of the characteristics of terrorism is to impede rational thinking, at least in the moment, leaving the targets helpless in the face of a brutality that seems incomprehensible because it is so profoundly unjust.

We consistently commemorate some of the major collective traumas that have marked our history, as with the future Museum and Memorial of Terrorism (MMT). What is the root of this memorial fervour?

H. R.: ‘Memory’ is a cardinal value of modern democratic societies, since about 50 years ago. Our need to remember has overridden the will to forget, which was advocated in the past as a means of encouraging reconciliation after a civil war or other conflict. Retracing the past used to be forbidden, which would seem unacceptable to us today. The anamnesis2 of the Holocaust that took place more than two generations after the end of the war, as well as that of the Vichy period and the Algerian War (both of which ended with amnesty decrees followed by a phase of amnesia), have obviously played a central role in France in the rise of this contemporary culture of memory – which extends on a planetary scale to other subjects, such as slavery and colonialism.

This desire to recognise the failures and crimes committed during those tragic periods, and in particular the urge to denounce the impunity of the perpetrators, explains our current willingness to take retrospective action on the past, to ‘correct’ it and better manage its consequences. Still, this does not mean that remembering the past necessarily prevents us from repeating it. Moreover, the role of the victims has changed considerably in recent years, especially in legal procedures. The figure of the hero has gradually faded, replaced by that of the victim.

Are there other sites in the world comparable to the future French memorial-museum?

H. R.: There are a great many memorials dedicated to the victims of terrorism, in the form of plaques, squares, gardens, street names, sculptural monuments… However, very few – only about half a dozen – offer a museum in parallel, and our commission has visited nearly all of them.

The first one of this type is in Oklahoma City (United States), inaugurated in April 2000 to commemorate an attack by the extreme right on a federal building on 19 April, 1995, taking the lives of 168 persons. In New York, the National September 11 Memorial Museum, underneath the former site of the World Trade Center twin towers, is most impressive, and interesting. It demonstrates the need for spatial and symbolic continuity between the memorial and the museum, and served as a model for us.

I should also mention the Tribute Museum, a few blocks from Ground Zero, which is much less spectacular and seems to be on the verge of closing; the 22 July Centre in Oslo, in homage to the victims of the attack in the capital and the Utoya Island massacre in 2011; and the Victims of Terrorism Memorial Centre that recently opened in Vitoria-Gasteiz, in the Basque region of Spain.

Nearly all of the memorial-museums outside of France focus on a specific attack and stand on the actual location of the ‘monster event’ – to use an expression coined by the French historian Pierre Nora. Will this be the case with the French project?

H. R.: No. Our project is not about one single attack, nor about a specific form of terrorism (anarchist, nationalist, third-worldist, independentist, anti-Semitic, extreme left, extreme right, Islamist, etc.), nor even about one particular country. It addresses all terrorist acts committed on French territory as well as those outside of France whose victims include French citizens, starting from 15 September, 1974, the date of the Drugstore Publicis attack on Boulevard Saint Germain in Paris.3

That terrorist strike, which killed two people and wounded 34, was the first deadly blind attack (targeting anonymous passers-by) committed on French soil after the end of the Algerian War. Also in 1974, France began attributing the National Medal of Recognition to victims of terrorism. In all, since the end of the 1960s, terrorism has claimed the lives of more than 800 French people (450 in France, affecting more than 400 communities of all sizes, plus 350 in other countries), making France the European nation that has paid the heaviest toll.

But the memorial-museum also has an international dimension, since modern-day terrorism is increasingly globalised, and it seeks to achieve a form of universalism in the name of moral equivalency among all victims.

Regarding its location, the choice fell on the former École de Plein Air (open air school) in the Paris suburb of Suresnes, on Mont-Valérien…

H. R.: It’s a listed historical monument, built in the 1930s for the benefit of chronically ill children. This exceptional building, surrounded by remarkable grounds but in need of renovation, is doubly symbolic, evoking resilience and care for the most vulnerable as well as the Résistance: the site adjoins the Mémorial de la France Combattante, a monument to the French fighters of World War II. The MMT is founded on a policy concerning the victims of terrorism and is intended as an act of cultural resistance against the brutality of terrorist actions, regardless of their origin.

The memorial part of the project will include the inscription of the names of all French citizens who have died in terrorist attacks in the past 50 years. Why is it so important to name the victims?

H. R.: In today’s mass society, we must never trivialise the victims of these attacks by reducing them to figures, to abstract statistics. It is essential to give life to their memory, restoring their identities and personalising each individual life destroyed by violence. In the words of the philosopher Vladimir Jankélévitch, a memorial 'brings out of the dark and the mists, by calling them by name, the countless anonymous ghosts annihilated by their executioners. To name these pale shadows is to bring them into the light of day.'

Of course, making as precise and exhaustive a list as possible of the victims, inscribing their names on a wall or other surface, perhaps displaying portraits, providing biographical information and excerpts of testimonies, broadcasting vocal accounts… All of this will be done, and is already being done in cooperation with the victims’ families and loved ones, under supervision by the appropriate legal and administrative authorities.

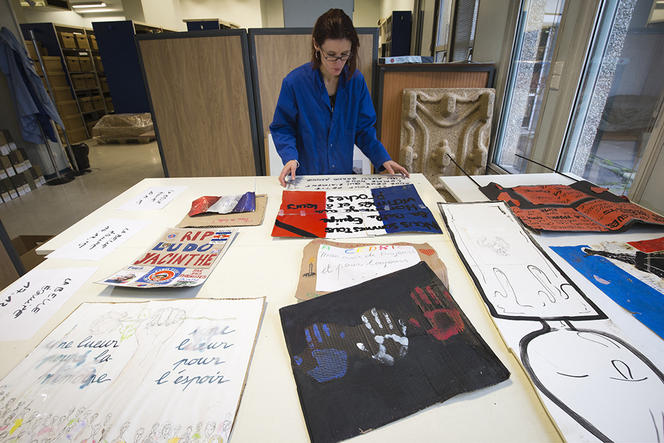

What kind of objects will be exhibited in the museum section?

H. R.: We are amassing a specific collection for the MMT. It will include objects contributed by victims’ associations or survivors themselves (clothing, telephones, children’s toys…), as well as artefacts from the site of the attack (drawings, candles, stuffed animals…) bearing witness to public expression of compassion. One of the key original aspects of the collection will be the inclusion of exhibits from closed legal proceedings. I hope that we will be able to obtain excerpts of filmed records from terrorism trials. We are also gathering institutional objects from police departments, material from private archives, whether printed, audiovisual or digital, plus artistic, literary and musical works, some of which will be especially designed for the site.

How will you avoid lapsing into voyeurism when exhibiting material remnants of the attacks?

H. R.: A terrorist attack is an act of war in a time of peace. Consequently, we must make people aware of its extreme violence and the subsequent risks that it poses to the national community (disruption of the social fabric, rejection of others, discrimination, disinformation, radicalisation). Nevertheless, we have no intention of following in the steps of terrorists, one of whose favourite weapons is to make a big show of violence in order to incite fear and draw public attention to their actions. We draw a clear-cut line between the euphemising of violence and sensationalism. We try to take the right distance, showing what a terrorist act is, while ensuring full respect for the victims, and calling upon visitors’ sensitivity, humanity and intelligence.

Another sensitive point: the place that should be given to the perpetrators of the attacks. Should the memorial merely mention their names or show their faces, at the risk of offering them the legacy that they were seeking and transforming the museum into a ‘pilgrimage site’ for other extremists?

H. R.: It goes without saying that there will be nothing even remotely resembling a glorification of the perpetrators and organisers of terrorist acts. But you can’t create a museum of the history of Nazism without mentioning Hitler by name or showing images of him. At the Oslo museum, for example, Anders Behring Breivik, the neo-Nazi murderer responsible for the attack that claimed 77 lives on Utoya Island in 2011, is shown almost exclusively as a defendant during his trial. The question that arises is 'how.'

The memorial-museum will be not only a place for exhibitions and paying homage, but also for research, education, prevention…

H. R.: Our goal is to make it a crossroads for dialogue and reflection on what terrorism, in all its forms and all around the world, has been since the French Revolution, and what it is today.

We will provide support for terrorism-related research, making the collections available, organising seminars, offering access to a database now being compiled on the attacks in France, funding scholarships for master’s degrees, doctorates and post-doctorate studies, hosting researchers in residence… The research projects can involve all disciplines (history, law, sociology, philosophy, anthropology, the neurosciences, etc.) and cover topics like the causes and consequences of political violence, the legal qualification of terrorist attacks, the status of the victims, individual and collective memory, post-traumatic stress, the role of mass media in the depiction and ‘monsterisation’ of terrorist acts…

What would be the point of acknowledgment without knowledge? We must offer people, especially the young, the keys to a better understanding of this process of hatred – backed by a long history that is not well understood due to the shock generated by each terrorist attack – and help them overcome the fear that it provokes. This will be, once again, a form of resistance against terrorism.

Isn’t it premature to be turning the history of terrorist attacks – in other words a history that is far from over – into the subject of a museum?

H. R.: It would simply be meaningless to wait for the end of a phenomenon that has been with us for years, and that we’ll probably have to put up with for a long time to come. The question calls to mind the debate on whether it is possible to write a history that’s always in the making, one that would be forever ‘unfinished’, therefore preventing historians from ‘taking a step back’. The Institut d’Histoire du Temps Présent, of which I have been a member nearly since its founding (1980) and which I headed for more than ten years (1994-2005), has demonstrated the legitimacy and value of this approach, formerly deemed dubious and even rejected outright due to the lack of distance from the facts being studied. We have developed theoretical and practical tools for writing this type of history. Lastly, it would be paradoxical for our society, which honours victims of older tragedies, to refuse to grant the same consideration to the more recent victims of terrorism.

Would you define the future memorial-museum as a place geared, despite it all, towards hope?

H. R.: Yes, because it will showcase the many examples of rescues, help, heroism and sympathy that take place with every attack, all those actions that stand as messages of hope. Similarly, it will celebrate all who strive to prevent terrorist attacks. And it will uphold the fundamental values of citizenship: freedom of expression, freedom of religion, equal rights, tolerance, and openness to the world.

- 1. The historian Henry Rousso is a CNRS research professor emeritus and the former director of the IHTP (Institute of History of Present Time – CNRS / Université Vincennes-Saint-Denis).

- 2. Recovery of repressed memories by individuals or populations.

- 3. Terrorist attack attributed by the French judiciary to the Venezuelan Ilich Ramirez Sanchez, aka Carlos, who was active in “anti-imperialist” terrorism in the 1970 and 1980s.

Explore more

Author

Philippe Testard-Vaillant is a journalist. He lives and works in south-eastern France. He has also authored and co-authored several books, including Le Guide du Paris savant (Paris: Belin) and Mon corps, la première merveille du monde (Paris: JC Lattès).