You are here

Digital Technology Becomes Central to Life in Confinement

The current confinement period is highlighting the essential place that digital tools have in our lives and the organisation of our societies. Mobile phones, computers, tablets… All of these connected devices play a determining role in how people deal with this unusual situation, enabling them to stay in contact with loved ones, pursue their professional activities, remote-manage everyday practical issues, maintain interactions between teachers and schoolchildren, stay abreast of the news, and access entertainment such as films, television series and video games. Of course, they were already commonly used before confinement, but for many of us this complete reorganisation of daily life has made our digital companions more important than ever.

This is so true that, as soon as the confinement order was announced, many began to wonder whether the online networks and service providers would have the capacity to handle the load increase and uphold their usual quality of service. In fact, certain platforms have decided to downgrade their standards in order to reduce bandwidth consumption. Generally, these reactions and this concern – among many others – oscillate between two indissociable questions. On the one hand, what would we do without digital technology in such a situation? And on the other hand, to what point does it encourage instructions to “carry on”?

Naturally, it is too soon to describe in detail all the uses of these devices in the exceptional context of confinement, and in particular to know whether today’s situation will give rise to new practices. But it is a very safe bet that any already widespread habits will intensify. In this area, the studies previously conducted by sociologists on the use of digital technology in private life, especially within the household, are a precious source of information.

An intensification of uses

It is important here to recall one of the key findings of this research: online practices, especially on the social networks, are closely intertwined with offline uses. For example, teenagers rely on these platforms to prolong their interactions with their peers when they are apart. They use apps like WhatsApp, Instagram and Messenger mostly to keep in touch with friends whom they usually see at school, during extracurricular activities or in their neighbourhood. These communication tools provide a continuity between the times they spend together and apart, especially when they are at home with their families, and can be more “conversational” (long exchanges on an occasional basis) or more “connected” (frequent or continuous) in nature.

It goes without saying that under the current circumstances, and not only for teenagers, the online and conventional telephone networks fulfil a crucial function, by maintaining essential social contacts between people who are separated, whether momentarily or for the duration of the confinement.

Another point to bear in mind is that while many of us are accustomed to using digital devices, there are still groups and individuals who have trouble, or even great difficulty, handling them. It is true that digital technology has become commonplace since the mid-2000s, with 86% of the French population having Internet access at home by 2019. However, certain social categories are disproportionately represented in the remaining 14%, including 60% of non-college graduates and 65% of seniors above 70, who also more often live alone. On average, the larger the household, the more likely it is to have an Internet connection, with a reception quality that depends mainly on the geographical zone (Crédoc, 2019). However, beyond these material considerations, the studies underline the extent to which practices, equipment, software and platforms vary according to users’ sociodemographic profiles. People’s online lives and habits are extremely varied, depending on factors that include social category (Pasquier, 2018).

A third element to be emphasised is that confinement does not automatically mean isolation or solitude. We have not all become hikikomori (a Japanese term for voluntary recluses) overnight, cutting ourselves off from all “offline” social life!

Sociological surveys have shown that the uses made of digital devices are very closely linked to the context – logically, the same is true in a “confined” situation. The issues involved in communication, information and activities, online or otherwise, can be quite different depending on whether the person concerned is living alone, as part of a couple, with or without children, as a single parent, etc.

The balance between remote exchanges and direct personal interactions within households (which themselves cover a wide range of sizes) is no doubt the most important question in a confinement situation. In certain cases, isolation can be the greatest, most acute problem, and in others a dreamed-of but unreachable perspective, a temporary respite from the presence of others. In households with multiple online equipment, the way communication devices are distributed in the space and the negotiation of rules governing their individual and collective use have, since long before the current crisis, been an indication of how successfully “privacy thresholds” and allowances for exchanges with the outside world are managed within the family home.

Tensions between private, professional and educational activities

Examining the use of digital devices in a period of confinement means looking into the interrelations between online and home life (especially in households comprising several persons). The advent of real-time communication tools for home use (the first being the landline telephone) raised a question: how can the rules governing the collective life of individuals living under the same roof be reconciled with the existence of systems enabling them to connect with people outside the home? Until what time in the evening is it acceptable to call a friend or family member? Can smartphones be used while the family is playing a game, relaxing together or sharing a meal?

Such questions proliferated when communication devices were individualised and acquired a professional or educational purpose: should children be allowed to interact on social networks in the evening, under the pretext of needing them to do their homework? When and how much should one pursue remote professional activities on weekends or while on holiday? Since last 16 March, when the confinement order went into effect in France, these issues have become even more topical, not only in the private sphere, but also in at least two other interconnected areas: that of educational practices for the sake of “pedagogical continuity” and that of professional activities and exchanges in the context of “remote working”.

Confinement has turned the family home into a venue for all types of educational and school activities. Previously called upon only to supervise homework and monitor academic results via virtual learning environments (VLEs), parents are now encouraged, or even obliged, to help their children study using the systems implemented by their teachers.

This requires not only managing schedules for children and their parents (or tutors), but also acquiring the necessary technical skills (often involving unfamiliar technologies and interfaces) and finding the intellectual resources to help children in their schoolwork and their interactions with teachers. This could mean, for example, defining set times to be devoted to study, having the courage to ask questions, finding forms that are considered acceptable for soliciting and replying to teachers, etc.

Lastly, those engaged in more or less intensive forms of distance working are faced with various challenges. Other than the fact that not all aspects of professional life are easily replicable via digital channels (the management of everyday interactions, spontaneous exchanges to settle simple questions, hierarchical relations, task control…), they must rethink their daily schedules and the management of online exchanges to coordinate their professional and personal activities. While the two have always overlapped, the issues surrounding the more or less specific principles that regulate such overlap are now of particular relevance.

Can weekends and “downtime” be maintained? Is it possible to disconnect with impunity? And if so, in what forms? Do the usual expectations in terms of responsiveness and availability remain unchanged? It seems indisputable that the spillover of professional responsibilities into the private sphere and into domestic life has increased tremendously since the enactment of the confinement order. But is it total and unlimited?

Changing habits and perceptions

The confinement period is disrupting, or at least calling into question, more or less well-regulated procedures and established habits. It is reasonable to think that the current situation will lead to changes in the rules that govern online as well as offline life. Between the need to shield moments of family togetherness against external solicitations and the necessity to deal with an exceptional situation, there is no doubt that the balance is being shifted or recreated. One might wonder about the long-term consequences (extending beyond the crisis itself) of the habits that will be formed and then permanently adopted during the weeks of confinement. Will individuals and families become more accepting of communication tools? Or, on the contrary, will they learn to do without them and be more cautious about their overuse? It is too early to say, but in any case, the answers to these questions are likely to vary according to the social, family and professional contexts.

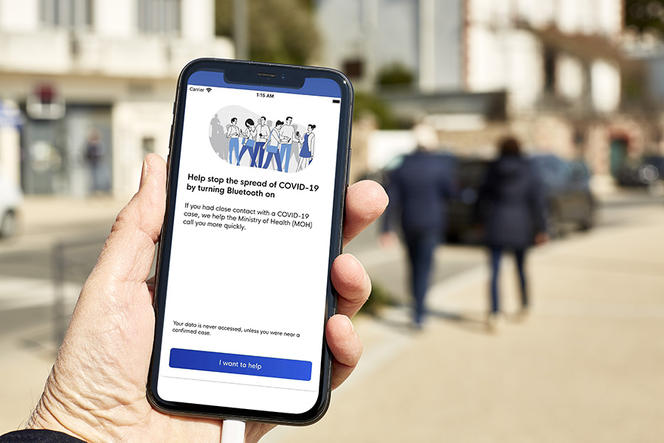

The growing importance of the role of digital activity during this period also challenges certain practices and promises, e.g. online shopping procedures that require a long chain of mechanisms and participants (ending with the delivery workers), making them more visible. These uncertainties also encompass controversies that go beyond technical aspects or the reliability of the systems involved. They extend to social, moral and ethical issues in which the geolocalisation of individuals in the “post-crisis” context is already a focal point, among others, in terms of personal freedom. From this point of view, digital factors are good indicators of social ones, due to existing inequalities in skills, equipment and modes of use, and also because technical mechanisms are linked to societal choices.

Lastly, it should be noted that confinement is probably made easier (at least relatively) in certain ways by the presence of digital devices. Without them, it would be much more difficult, not to say impossible, to partially compensate for the closing of schools and many businesses. Remote communication techniques are seen as resources for ensuring pedagogical continuity, as well as for maintaining essential management and administrative operations. From this perspective, this is a crisis presumed to be partly surmountable thanks to digital technology, even if this poses a new problem – that of harmoniously accommodating all of the activities (work, education, leisure, personal relations) that are now concentrated in a single place, occurring all at once, and no longer delegated to external services (schools, workplaces, etc.).

At the same time, digital tools are clearly showing their limits. They cannot replace all forms of interaction, dialogue and activity. Without even mentioning manufacturing, industrial and agricultural operations (in which they play an ever-greater role, even though remote communication remains less central to the production processes), digital technologies can only provide part of the educational content, daily exchanges in the workplace, or the pleasures of socialising with friends. And therein lies an essential lesson: they allow us to do many things, but not everything. Confinement is demonstrating that digital devices enable certain forms of continuity without being a solution or substitute for every aspect of life. Our societies tend to amalgamate digital and non-digital practices. To hope or believe that only one of the two could suffice to sustain a thriving society is totally illusory.

The points of view, opinions, and analyses published in this article are solely those of the author They do not in any way constitute a statement of position by the CNRS.

Further reading

- Julie Baillet, Patricia Croutte and Victor Prieur, “Baromètre du Numérique 2019. Enquête sur la diffusion des technologies de l’information et de la communication dans la société française en 2019”, Crédoc, November 2019. - Jean-Samuel Beuscart, Éric Dagiral and Sylvain Parasie, Sociologie d’Internet, Paris, Armand Colin, 2019. - Christian Licoppe, “Sociability and Communication Technology Two Modes of Maintaining Interpersonal Relations in the Context of Mobile Communications”, Réseaux, vol. 112-113, n°2, 2002, p. 172-210. - Martin Olivier and Éric Dagiral, L’Ordinaire d’Internet. Le Web dans nos pratiques et relations sociales, Armand Colin, 2016. - Dominique Pasquier, L’Internet des familles modestes. Enquête dans la France rurale, Presse des Mines, 2018. - Anne-Sylvie Pharabod, “Territoires et seuils de l’intimité familiale. Un regard ethnographique sur les objets multimédias et leurs usages dans quelques foyers franciliens”, Réseaux, vol. 123, n°1, 2004, p. 85-117.