You are here

Resistance in Ukraine is also digital

The Russian invasion of Ukraine, which began on 24 February, is also a war "of" and "by" digital technology. It has had a considerable impact on the cyberspace of both countries, due to drastic modifications to Internet regulations in Russia, as well as international sanctions which, among other things, prompted many digital companies to leave the country. In Ukraine, physical infrastructure has of course been severely damaged by military operations. Massive cyberattacks against government services on both sides were initiated by citizens, hackers, and state agents, while disinformation campaigns led by the Kremlin have flooded Russian social media.

Cutting off the Russian Internet from the rest of the world

While the war in Ukraine has shined a spotlight on these various developments, it should be noted that they are longstanding dynamics that the ResisTIC project has been analysing over the past four years. Since the 2010s the Russian authorities have been actively pursuing a strategy of digital sovereignty, in an effort to make the RuNet autonomous through new laws countering foreign influence. Another example of this policy is the Sovereign Internet Law passed in 2019 to protect the country from cyberattacks, or the “anti-Apple” law enforced in 2020 with a view to pre-downloading a host of Russian-produced applications on smartphones sold in Russia.

Furthermore, one of the Russian government's stated objectives is the ability, “if necessary”, to physically isolate the Russian Internet from the rest of the world, especially through two key measures. The first is the creation of its own version of the Domain Name System (DNS), in order to continue operating if links to servers located abroad are cut off.

The second requires Internet service providers (ISP) to show that they can direct Internet traffic exclusively towards exchange points controlled by the government, so that only data exchanged between Russians reaches its destination.

Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter slowed down or blocked

Over the last decade, every effort has been made to expand the scope of the Roskomnadzor (RKN), the federal government's communications control body. It is now involved in areas as diverse as the monitoring of online content, the right to block websites, and their registering, which has considerably increased its possibilities for censorship. This has been made possible by an important infrastructure-related lever for controlling the Russian Internet, the Tehnicheskiye Sredstva Protivostoyaniya Ugrozam (TSPU), which can be translated as “technical means for countering threats”.

The RKN can considerably slow or partially block the most popular social media in Russia. Russian anti-war activists were thus cut off from the primary foreign information services. Others will soon follow, as the new deep packet inspection (DPI) system – organised by the TSPU and installed on the majority of Russian networks – is currently being used to slow or block Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter, as well as to block independent media. The goal, of course, is to control narratives of the ongoing war, which the Russian government still refuses to name as such.

The conflict has also introduced new risks. Ukrainian citizens and Russian anti-war activists are both subject to the same threat, which is very specific to the war, namely partial or total Internet outages. In the case of Ukraine, these connectivity disruptions are primarily caused by physical damage to optical cables or relay antennas resulting from military operations. On the Russian side, these interruptions are orchestrated from above, most often by the RKN via the TSPU system.

The ever-increasing legal and technical constraints weighing on the Russian Internet over the last decade have sparked resistance and adaptation by Russian Internet users, which the current situation has brought to the forefront by emphasizing similar strategies developed by Ukrainians.

For instance, despite the poor quality of its encryption, the secure messaging service Telegram – supposed to be “unblockable” – has become the primary communication tool for Russians and Ukrainians since 24 February 2022. It is used to spread more or less independent information, as well as first-hand video and photo documentation of the war. It is also the main service used by Ukrainians to coordinate in emergency situations, as well as by Russian activists to organise anti-war actions and to synchronise support for arrested activists.

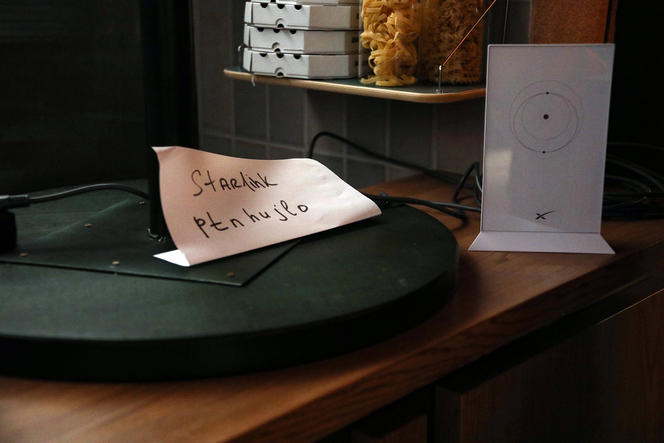

DIY and brainpower bring the Internet into bunkers

This new context has also led citizens of both countries to find reliable alternatives when the “conventional” Internet is not working. The prospect of being totally or partially disconnected has prompted users to rely on “old” protocols or tools such as text messages and regular telephone calls, as well as emails. Ukrainians call and text their loved ones staying in bomb shelters for days on end without Internet access, while Ukrainian ISPs are working to bring the Net into bunkers through “DIY” and flexibility that has been a feature of the Ukrainian Internet1 for a long time.

Opposition media in Russia has returned to “traditional” distribution lists to share information on the war, as their websites have officially been blocked. For the majority of people living in a war context, digital security is less of a priority than connectivity: it is better to have unsecured communication than no communication at all. However, groups of users with more advanced technical skills have initiated digital “migrations”, and are advocating wider use of decentralised encrypted messaging services such as Briar, Matrix, and Delta Chat. Russians and Ukrainians who oppose this war, both in principle and in their everyday practices, are using the same technologies to protect themselves from very similar enemies. They share the same vision of a digital world in which freedom of information is guaranteed, and the right to privacy is protected.

The views, opinions and analyses published in this column are the sole responsibility of their author(s). In no way do they reflect the position of the CNRS.

- 1. Read the article “How Ukraine's Internet Can Fend Off Russian Attacks” published in the magazine Wired on 1 March 2022.