You are here

Spyware in mobile games

Candy Crush, Pokémon Go, Clash of Clans, Roblox… The list goes on. Mobile games have enjoyed great success among users. How important have they become in recent years?

Pierre Laperdrix:1 The industry has indeed grown tremendously, with increasing spending on mobile games and more and more players. In 2021, it was estimated that the latter totalled nearly 2.6 billion across the globe, generating revenues of $93.2 billion. For the first time ever, the revenues of games on mobiles this year surpassed those on PCs and consoles put together. The trend was amplified during the lockdown, as many people did not necessarily have gaming consoles or computers at home, and used what they had at hand to entertain themselves!

What is the economic model of these games, and what role does tracking play?

P. L.: There are multiple ways to monetise a mobile game. The first is online advertising, in which the game’s developer or publisher receives a little money for each advertisement presented to the player. Today this is the most common method, as 95% of games on Google Play Store are free, and therefore indirectly financed by such ads. There are also microtransaction systems in which a few euros are paid to unlock items or new levels in the game. In addition, subscriptions such as the ‘Battle Pass’ give access to additional content for a few months. And finally, there’s the purchase of the game by its users.

Today a large part of the Internet is financed by online advertising. To have the greatest impact – the most likely to lead to a purchase – it must be as targeted as possible. A huge industry thus emerged to profile each user as accurately as possible, and to then present them with advertising that best matches their centres of interest or consumption habits. Spyware collects as much data as possible thereon: what one does on the Internet, what games they play, their geographic location, etc. This information is sometimes sold to third-party companies to earn more income. This advertising ecosystem is gigantic, with thousands of businesses collecting and sharing profiles, including GAFAM as well as more local enterprises such as Criteo in France.

You conducted a study on the presence and functioning of different trackers in mobile games. How did you proceed?

P. L.: We used Android telephones to conduct the study on games available in the Google Play Store. We downloaded all of the free ones from the AndroZoo database, which is maintained by the University of Luxembourg. For paid games, we used the free trial from the Google Play Pass catalogue. This provided us with a database of 6,751 games, including 396 paid ones. We then turned to the online service Exodus, an analysis tool that shows which spyware is contained by an application, in order to study the games on our list.

You noted that trackers are not distributed in the same manner in free games and paid ones.

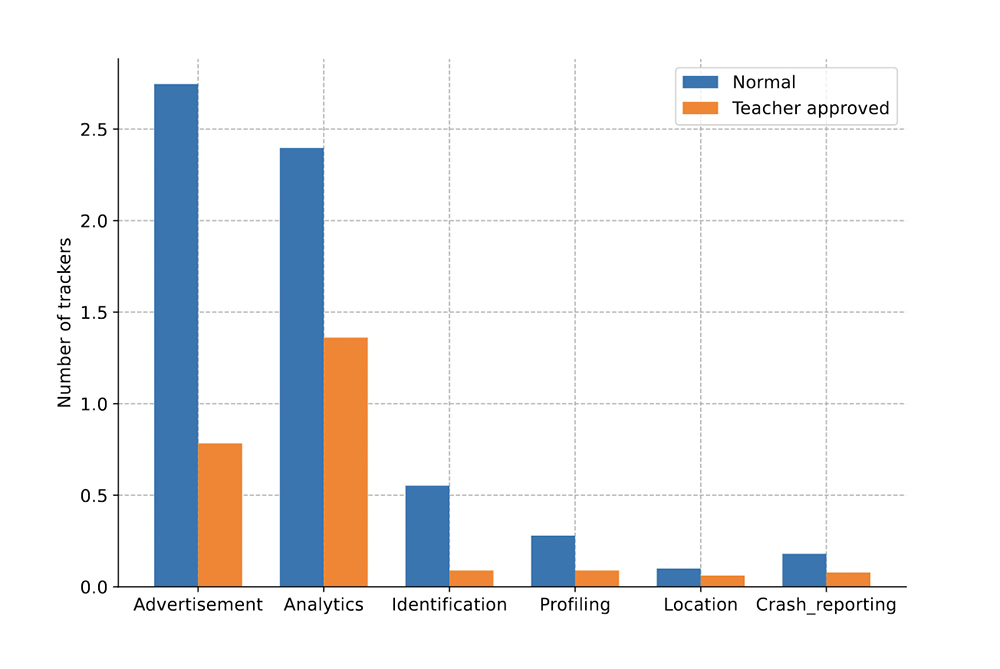

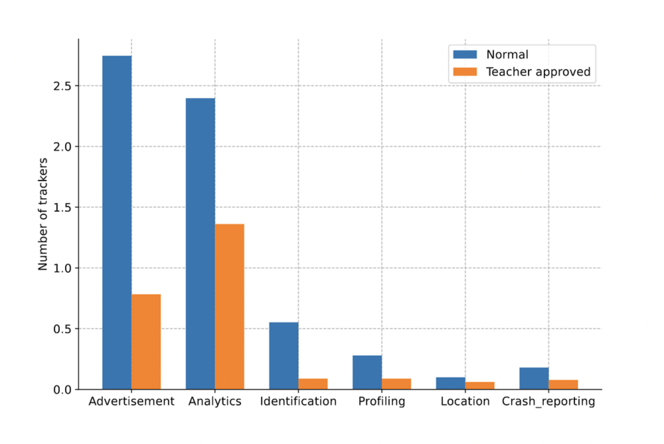

P. L.: In our study, 87% of free games had at least one spyware, compared with 65% of paid ones. Even in the latter, there is no guarantee that you won’t be tracked. It is important to understand that there are multiple types of tracking. Ad trackers aim to gather information regarding users for advertising purposes, while analytics spyware shows how the application is used (for example if the player needs more or less time to complete a particular level). This of course involves collecting data, but it is not connected to the user’s identity. Free games generally include both ad and analytics trackers, while paid games, which contain five times less advertising, mostly integrate analytics spyware.

Does the quantity of trackers also change according to the category of the game?

P. L.: Yes. The games with the most trackers are those in the ‘Casual’ category in the Play Store. They consist in short and simple games, such as Candy Crush or Clash Royale. We believe this is because their users tend to install many similar applications and play them for a few minutes to determine whether they want to carry on – before uninstalling many of them. Including many trackers thus allows for gathering as much information as possible in a short period of time, even if the app is used for ten minutes and then removed.

On the contrary, an application on which one spends hours over several months will have much more time to collect data. Educational games are those with the fewest trackers, but they nonetheless have them, with an average of 2.12, as opposed to 6.1 in free games. It is important to note that not everything depends on the number of trackers, as a single one can collect an enormous amount of information on its own, and share it with millions of companies.

Is it possible to know what data is shared, and with whom?

P. L.: No, all of this is very opaque. For example, I have no idea whether the location data on Pokémon Go is used simply to know where to find the game’s creatures, or whether this information is also shared with other partners. We have no clue whether a company gathers such material to exchange it with another firm or with three thousand. Even since the enforcement of the GDPR2 – which requires businesses to be more transparent regarding what they collect and the partners to whom they communicate this intelligence –, it is still very difficult to control.

What risks does this entail for users, their privacy, and more generally for society? What excesses should we be worried about?

P. L.: Since we don’t know what data is recorded and exchanged between different companies, we are unaware of the impact this can have on our lives. It could be minor if the information collected is minimal, but it can also be very disturbing if it is highly personal or precise, and could directly lead back to you as a person. For example, if you connect to an application using your Facebook account, it is possible to link what is happening in the game with your online profile, which contains your last name, first name, telephone number, and sometimes even your network of friends, the various Facebook pages you follow, and the country where you are, among other things.

So indeed, there are risks! While most advertising simply tries to get you to make a purchase, there have been excesses during political elections, for instance with the Cambridge Analytica scandal,3 where electoral ads were placed on Facebook to influence voting during the 2016 presidential campaign in the United States. It can therefore have fairly serious consequences, but it hardly ever happens. Some people are also afraid of leaks, but those are also very rare. It is important to remember that everyone is tracked on the Internet today. As an ‘ordinary’ citizen, we are a drop in an ocean of data gathered on the Internet.

How can we guard against such dangers?

P. L.: I believe a first step needs to be taken in our society, and that is to make people aware of these issues. Perhaps they will engage in more prudent behaviour. But it is truly the responsibility of platforms to implement protection systems, because we cannot place this burden on users! I am optimistic for the future because for a number of years now we have seen legislative changes in Europe, as well as greater awareness on the part of large companies. In 2021, Apple added App Tracking Transparency (ATT) to its iPhones, which systematically asks users opening a new application on iOS whether they accept being tracked. Previously this was the case by default, and one had to explicitly refuse tracking, which is still true on Android. For several months now, a summary on Google Play Store indicates the different types of data collected for each game. It offers a two-line overview of what really happens – unlike the usual terms and conditions, which are endless, and that nobody reads. Despite all this, there is still no mechanism or alternative operating system that could give access to the same game without being tracked.

- 1. Pierre Laperdrix is a CNRS researcher at the Research Centre in Computer Science, Signal and Automatics of Lille (CRIStAL – CNRS / Centrale Lille Institut / Université de Lille).

- 2. The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), adopted by the European Parliament in April 2016, governs the processing of personal data in the European Union. It reinforced information and transparency requirements towards individuals in connection with the processing of their personal data.

- 3. https://time.com/5197255/facebook-cambridge-analytica-donald-trump-ads-d...