You are here

Notre Dame: restoring eternity

On 15 April 2019, the whole world watched helplessly as Notre-Dame burned. Where were you when you heard the news?

Livio De Luca.1 I remember I was in the train, I had just left Paris. When I received my wife’s message with the news, I was in shock. I remember walking past the cathedral on my way to the train station a few hours earlier. I followed the news nonstop until late that night. I immediately thought about the fire’s potential consequences on the building.

At the time, I directed the Models and Simulations for Architecture and Heritage Laboratory2 in Marseille. My colleagues and I were concerned, we wondered if there was something we could do. The very next day the Ministry of Culture asked me about the availability of digital data on the cathedral before the fire. I soon became involved.

You were initially an architect. What led you to work on the digitisation of heritage?

L. D. L. When I began my architecture studies in Italy, I quickly became fascinated by what information technology could provide in this field. I am from the generation born with computers, and so I have always viewed scientific disciplines in this context of digital transition, which is technological as well as methodological. Wanting to expand my knowledge in information technology in order to combine it with architecture, I came to France to complete a Master’s and then a PhD in computer engineering, ultimately obtaining an authorisation to supervise research in information technology. During this specialisation, I continued my interest in historical constructions. By working in heritage science, I discovered a whole world encompassing over twenty disciplines studying the same object, with hybrid profiles combining knowledge in architecture, archaeology, engineering, physics, and materials chemistry. An interdisciplinary approach is central to my work, not just as scientific practice, but also as a subject of study itself.

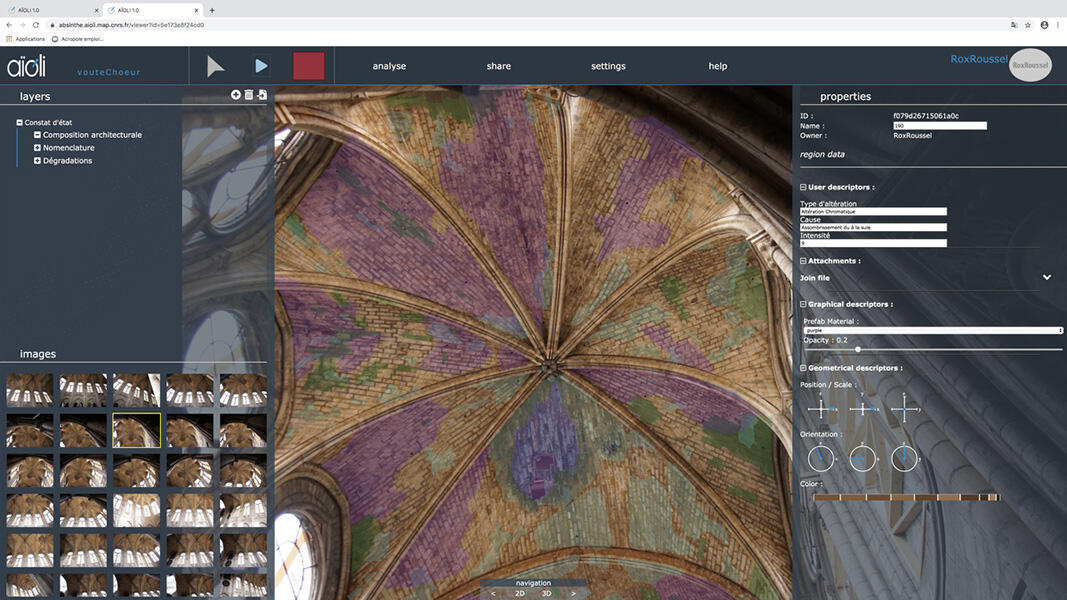

Over the last twenty years, I have experimented with the potential of 3D digitisation and information systems for numerous monuments in France and abroad, the bridge of Avignon in particular. I have also worked on the representation of knowledge. A building can be approached from multiple perspectives: each discipline and actor has a different way of describing it. In my laboratory we created Aïoli, a 3D semantic annotation platform for the collaborative documentation of heritage objects. We completed the first prototype in 2019, right before the Notre-Dame fire.

How did the scientific community mobilise around the cathedral, and what role did you play?

L. D. L. After the fire, a multitude of researchers spontaneously came forward, making their expertise available for the cathedral’s restoration. One hundred and seventy-five scientists worked on this project! In September 2019, the Ministry of Culture and the CNRS implemented a scientific effort spanning nine thematic working groups: wood and framework, metal, stained glass, stone and mortar, monumental décor, structures, acoustics, digital data, and emotions and mobilisation connected to the cathedral. I am the coordinator for the digital working group, which includes 12 laboratories and 40 researchers and engineers in France, along with collaborations abroad. With this group I developed the project for a digital twin of Notre-Dame. More specifically, it is a system that includes exhaustive data and knowledge of the various scientific fields connected to the monument.

How does this system function?

L. D. L. On the technological level, it is a platform accessible on the Internet that connects multiple software programs in order to manage the entire data lifecycle, from ingestion to long-term conservation. It is collaborative and allows for the semantic enrichment of data on multiple levels. With Aïoli, each user–in our case the scientists taking part in the effort–can create a new project simply by uploading photographs onto the platform, which are processed by the server and spatialised in 3D. The user then creates description duplicates that they can annotate. The user can view specific areas of the cathedral on the platform, for instance by clicking on an arch represented in 3D, which is linked to a series of photographs that include annotations from the different researchers working on the project. For instance, the user can find observations made by architects indicating that a particular section should be cleaned or repaired, or from a chemist indicating that a sample was taken from a material in 2000, and providing precise data from its analysis in the laboratory.

The information gradually accumulates, and we arrive at a layering of knowledge for the same object across different temporalities: before the fire, after the fire, during the different phases of restoration, after restoration. Today there are 13,000 annotations on the platform, and a multitude of users can add new data over time. It is a multi-temporal memorisation tool, which evolves as information is added. It is an extraordinarily rich object.

Did you encounter difficulties during the project?

L. D. L. In the beginning, we imagined that everyone would spontaneously use the platform, but that was not the case, for it did not necessarily meet immediate needs. Some researchers preferred concentrating on their work and integrating data later, once their research was finished. And that is understandable! Grasping that a common interest had to be built around this project, we changed approach by focusing on “scientific trajectories,” subjects on which the working groups collaborated. In this manner, the production of data responded to a specific scientific issue. Today we have ten trajectories, such as the creation of a complete digital diagnostic of the cathedral’s state of health after the fire, the availability of all knowledge on the framework before the fire, and analysis of traces of polychromy on the western façade. Another issue was the conflicting temporalities of the two efforts. The limited timeframe of the restoration effort provided a sense of urgency to the scientific effort. Researchers tend to think over the long term, but we sometimes had to produce data for a specific action, and provide quick answers. If we did not always have time to conduct experiments during the restoration, we could do so later.

What were the platform’s initial contributions?

L. D. L. Our work enabled the creation of anastyloses, which is to say block-by-block reconstructions of the destroyed sections of the monument. The platform helped us identify hundreds of the cathedral’s elements that had collapsed, to find where they had fallen, and to put them back in their original place. To do so, we based ourselves on laser scans made by the historian Andrew Tallon between 2006 and 2012–he passed away in 2018–as well as photographs taken before the fire. We also used photographs documenting efforts to recover the collapsed remains, in addition to 3D digitisations we had created ourselves.

By analysing all of these images, we obtained representations of multiple temporal states, allowing us to determine with certainty the origin of the remains in relation to the original structures. This made it possible to reconstruct the oculus–a round opening at the top of the vault–and to find the location for 80% of the stones from the transverse arch of the nave. Arch stones are hand-carved blocks, each with different dimensions—it was a major challenge. Our method also helped find the location for many of the burned beams from the framework recovered after the fire, especially those made of oak, the oldest ones from the roof structure over the choir. The trees used to build it were felled in 1185.

What are the next avenues for exploration, the questions that remain unanswered?

L. D. L. On the digital side, we are reflecting on the platform’s terminological component. Many texts have been produced based on annotations provided by users. We are beginning to work with the Opentheso software, which structures specialised vocabulary. Our goal is to calculate and represent occurrences, as well as to identify key terms, those that are more connected to others. The objective is to map this galaxy of connections between multiple objects of knowledge, and to connect them to the material object. The same object is viewed and interpreted differently depending on the specialists, who have different thought processes, and sometimes use different vocabulary to define it. What framework can we establish amid this range of views and knowledge? It is an open question.

With respect to other studies currently underway, numerous aspects remain unexplored. I am thinking, for example, of Notre-Dame’s rood screen, a major archaeological discovery that occurred during the restoration effort. A rood screen is a decorated enclosure that separates the choir from the cathedral nave. Built around 1230, it was dismantled in the early eighteenth century. The excavations conducted by the French National Institute for Preventive Archaeological Research revealed over 1,000 fragments, including hundreds presenting polychromy dating from the thirteenth century. This discovery raises numerous questions regarding its construction, evolution, and destruction, combining aspects relating to materials, production techniques, and pigment analysis. Multiple scientists will collaborate to study the screen, understand its composition, and reconstruct it.

As the restoration effort comes to an end, what will become of all this digital data and combined knowledge?

L. D. L. Research on the cathedral will not stop with the end of restoration: a permanent scientific effort (thematic network to study monumental heritage) was put in place. As a result, we will continue to enrich the platform over time, and hope to make this data accessible to a wide audience as part of an open science model. We therefore have to reflect on its implementation, as some data can be more sensitive. We are also working with the future museum dedicated to the cathedral, which will be located in l’Hôtel-Dieu in Paris, so that this data is interconnected with the collections presented to the public. The principle will also be applied to other projects, notably connecting with a large-scale programme: the creation of a European cloud for cultural heritage. This project, which will proceed over the next five years, will provide an opportunity to transmit the methods developed during the scientific effort connected to Notre-Dame. But it will be much more important!

It will not be enough to simply provide the tools we developed: we should also transmit methodological aspects, along with the very important social dimension of such a system. This platform took life thanks to a common attachment to the cathedral, shared objectives, and a collaborative logic. In our misfortune, we had a piece of luck: the fire made the cathedral into a unique object of engagement for the scientific community, a common denominator for a large body of knowledge. It is a major first. In the years to come, I think this experience will be central to the French contribution to heritage science.