You are here

Shelved Inventions

In keeping with the policy of support for inventions, every object was not only photographable, but also had to be photographed. Far from being motivated by artistic ambitions, these photographs are in fact utilitarian in nature. Although the photographers are never credited, the name of the inventor is consistently mentioned, and sometimes that of the person who commissioned the image. The images are almost always given a title, that of the invention. Whether still or moving, the image is entirely in the service of the invention.

Of the hundreds of inventions systematically photographed beginning in 1917, how many actually resulted in mass-produced everyday objects? How many contributed to a major scientific discovery? The history of this policy for inventions produced in this context is complex, and characterized by hesitation, failure, and a lack of success. Many projects were shelved, for varying reasons. In this respect the Direction des inventions served as a kind of laboratory. It brought together individuals from different backgrounds in pursuit of common goals. They conducted experiments and tests, and were not troubled if things didn’t work. They would fail better next time, to use Samuel Beckett's famous phrase.

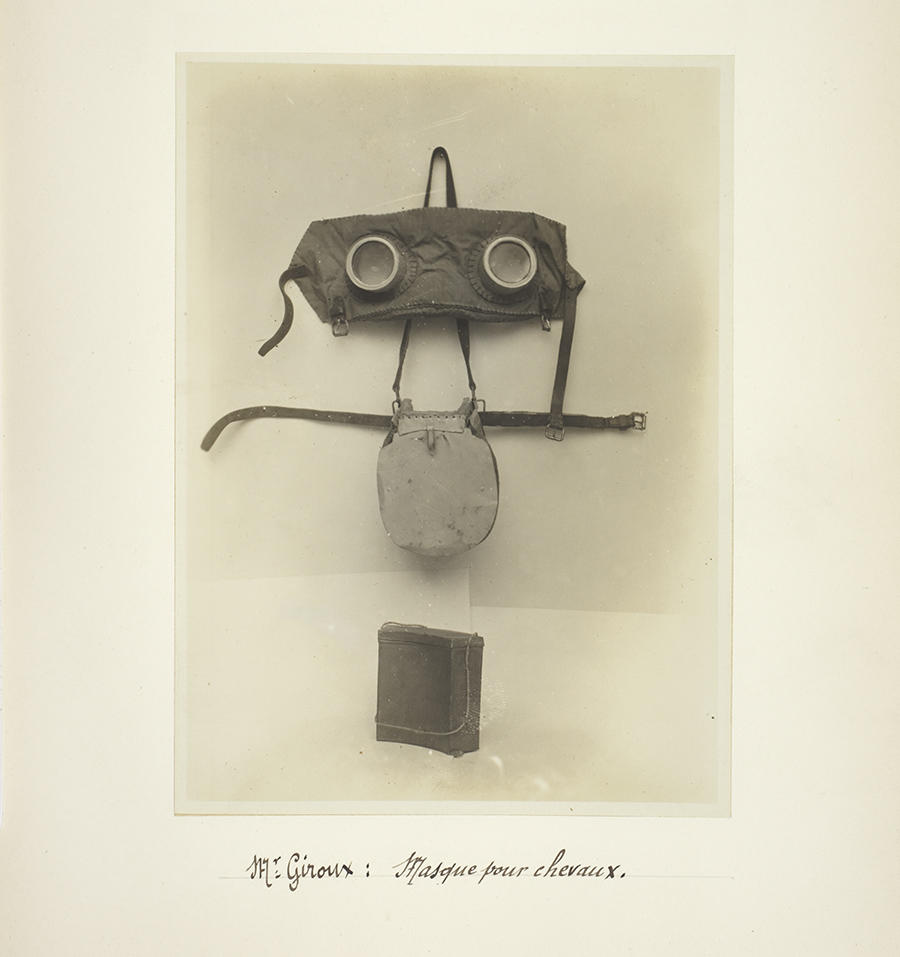

An unconvincing gas mask for horses

The horse gas mask proposed by the associate Giroux in 1918 is a good example of a miss. Beginning in the spring of 1915, both the horses that drew loads and the mules that carried machine guns shared the fate of combatants. They had to contend with the effects of gas attacks, which included suffocation from chlorine derivatives and burns from vesicant gas. The Giroux mask was one of the various prototypes evaluated in this context. Deemed too heavy and insufficiently airtight, the model failed to convince.

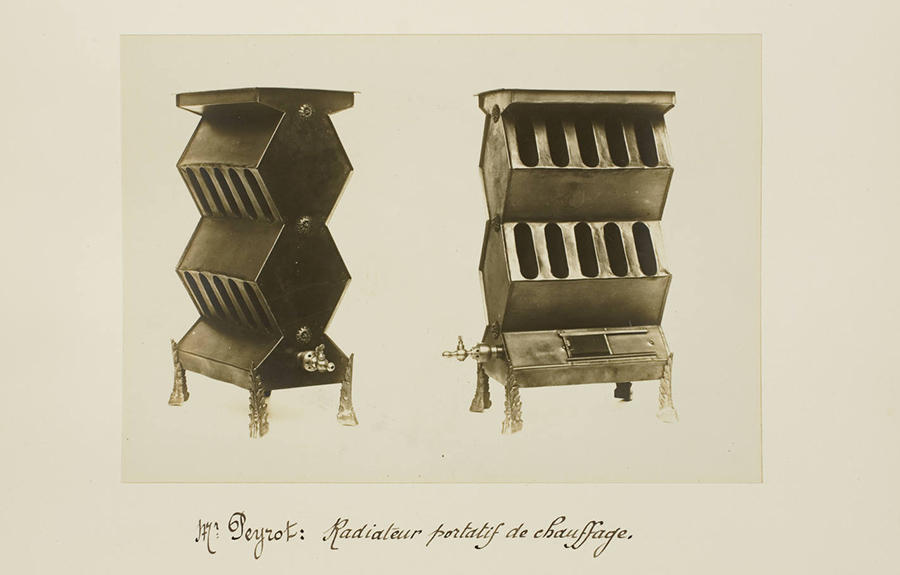

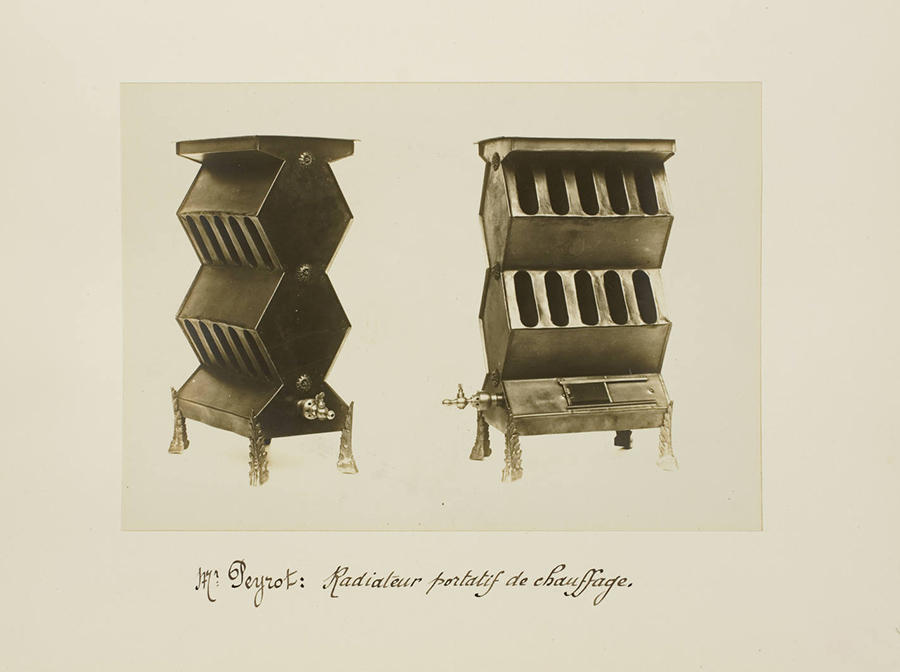

Cold reception for portable heating

The portable radiator designed by Peyrot met with still less favour among the experts at the Direction des inventions, with the report clearly stating that there is "nothing to retain." This invention even revealed a lack of knowledge regarding the very principle behind the radiator. This faulty radiator nevertheless touched on one of the major concerns of the war, combatting and preparing for the cold. The enemy was far from the only adversity encountered by French troops. Living conditions in the trenches made each day a struggle, especially in winter when blankets and jackets were the only way of keeping warm. This radiator also had the advantage of being portable, which was one of the features sought by the Commission supérieure des inventions (Inventions Commission).

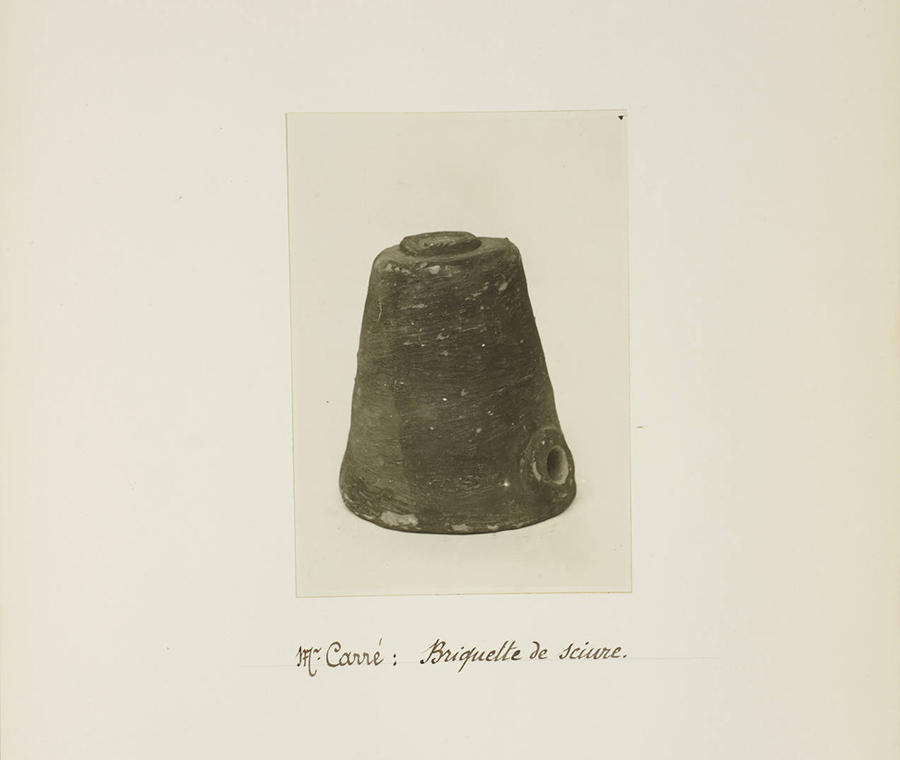

Sawdust briquette, case closed

Reticence on the part of the inventor could also be a reason for abandoning a project. This was notably the case for Monsieur Carré's Sawdust briquette. While it was easy to guess that it was a cluster of sawdust meant to replace firewood, it was difficult to discern what made it distinctive: "As the inventor preferred not to provide any explanation to this effect, the project was abandoned," the invention report concludes.

It is a long road between an idea and an invention. There is much fumbling, wandering, and failed tests along the way. The inventions archive tells the story of this research as it unfolded over the years. In the words of Beckett2 : "Try. Fail. Try again. Fail again. Fail better"1

From 1 July to 22 September, the CNRS will present its archives at the Rencontres d’Arles, in the form of a major photography exhibit entitled “La saga des inventions. Du masque à gaz à la machine à laver - Les archives du CNRS” (The Saga of Inventions: From the Gas Mask to the Washing Machine–the Archives of the CNRS).

- 1. “Ever Tried. Ever Failed. No Matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better,” in Worstward Ho, Calder, 1983.