You are here

An Ultra-fast Saliva Test to Detect Covid-19

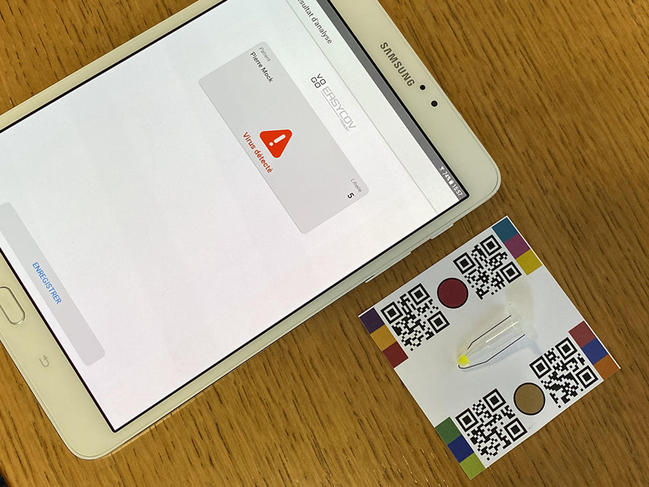

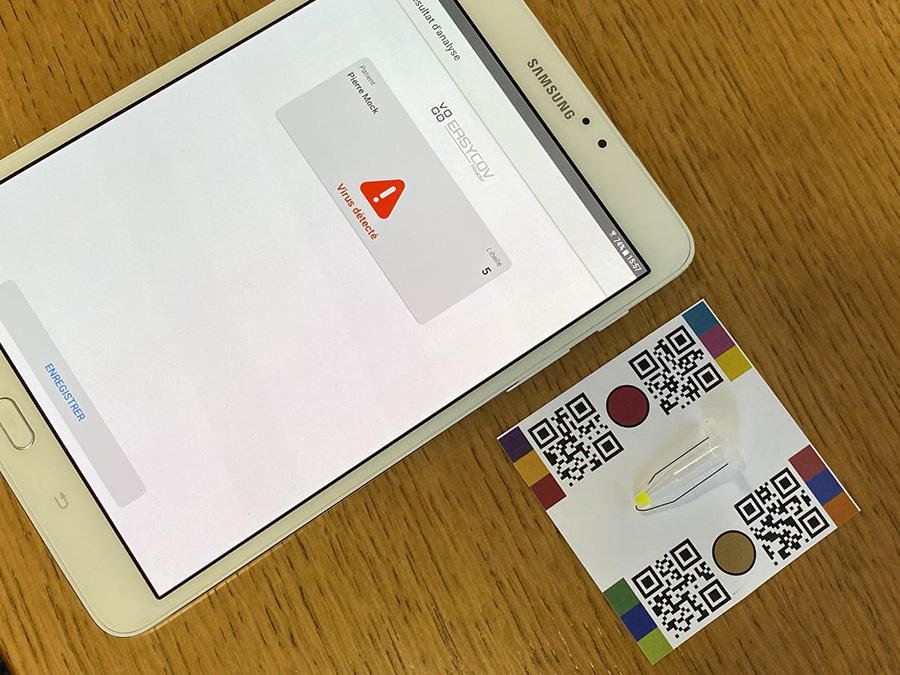

Is this the end of swabs thrust into the nasal cavities, robots that run for hours in medical testing laboratories and innumerable litres of reagent? Since 15 June, a revolutionary test has been able to diagnose in the field and (almost) immediately those patients who are suffering from Covid-19: called EasyCov, this portable system requires a few drops of saliva, a test tube and less than one hour of heating at 65° to produce a result. Another small reason for pride is that it has been developed by Sys2diag,1 a laboratory that associates scientists from the CNRS and from the companies Alcediag and SkillCell (Alcen Group), all led by the biologist Franck Molina. This test will accelerate and enable much broader coverage for the testing strategy recommended by the WHO since the start of the pandemic.

“Originally, Sys2diag did not specialise in viral detection,” explains Franck Molina. “Our core activity is the development of innovative diagnostic tools, and until now we have mostly worked in the field of psychiatry – on a test that can detect severe depression and the risk of self-harm – as well as on cellular machines, which are artificial cells that behave like small computers and are, for example, capable of detecting prediabetes in a patient’s urine specimen. But when the Covid epidemic started to accelerate in France and problems regarding tests and reagents were becoming evident, we decided that we ought to try something, based on the technologies and skills we had already developed.” So just before lockdown, when everyone in the laboratory was preparing to work from home, the team decided to initiate research on a saliva test.

“The idea was to produce a simple and easy-to-use method which could avoid the purchase of large machines that consume a great deal of reagent,” recounts Franck Molina. “We also wanted to find another way of looking for the virus than at the back of the nose – a procedure that can be painful for the patient and unsafe for the healthcare worker because it is uncomfortable and may trigger a sneeze. The question then was where to find the virus in large quantities, apart from in nasal secretions. The answer was: in the saliva. This was a risky choice and we are the only ones in the world to have made it, because saliva, which is full of enzymes, bacteria and cells, is known to be an important biological disruptor.”

Like the standard tests, EasyCov searches for the RNA of the virus – which does not of course contain any DNA – and therefore requires a host to transcribe its RNA into DNA and then reproduce. However, the technological choice made by Sys2Diag to achieve this was radically different. “The tests used by medical laboratories, called RT-PCR, function in three stages and successive cycles at different temperatures,” details Franck Molina. “First of all, they extract the RNA from the virus; they then transcribe it into DNA, which is amplified until there is a sufficient quantity to produce a reading. Our system relies on quite an old but little known technology called “RT-LAMP” which can do everything at once: the enzymes we use work simultaneously and all procedures are completed at the same time, at a single operating temperature of 65°C.”

“This is cutting-edge biochemistry,” admits the scientist, as a period of two to three years – rather than two to three months – is usually necessary to produce a marketable product. “We have had to overcome all sorts of problems to achieve this,” he adds. “But the most difficult thing was to obtain the reagents for our procedures. We ordered them from around Europe and they tricked in…” There were also some chilling moments, such as the week in April when all the tests performed by the laboratory suddenly produced positive results! “We realised afterwards that it was the reagent we had received from one of our suppliers that was itself contaminated by the virus, but at the time it really undermined our confidence.”

One thing is certain: the team would not have been able to achieve their goal without help from the entire ecosystem. “When we ran out of reagents, other laboratories in Montpellier (southern France) opened their cupboards and supplied us. The Occitanie Regional Council pre-ordered several thousand tests, even though we were not yet certain that it would be successful one day. As for the CNRS regional delegation, they made every effort to help us, drawing up contracts overnight to obtain urgent supplies of the attenuated virus.” And all this was happening while everyone, including the Sys2diag teams, was locked down at home.

“Initially, I was the only one coming to the laboratory, for videoconferences,” Franck Molina goes on. “I am in fact one of the twelve members of the Covid-19 research committee (CARE) that advises the French government on tests, vaccines and therapies. All other team members were working remotely and looking after orders for reagents, contracts and thousands of other things. Then one scientist joined me, then two, then three, until there were ten of us in the lab. We ordered meals to eat at our desks, because none of us had the time to go shopping!”

Yet Franck Molina is convinced that the key to the success of EasyCov was the public-private partnership from which he benefited: “To develop and industrialise a test in just three months, inventing something in the lab was not enough, we had to include clinical and industrial aspects very rapidly. When you have all three, you can move on quickly and make it!” The clinical tests were performed in April and May on 133 patients at Montpellier University Hospital, while the industrial partner, SkillCell, was making arrangements to launch production as soon as possible. “They trusted us, even though nothing had yet been validated.”

Today, 200,000 kits are being produced each week and sold in France via the Enovie group of medical testing laboratories. Although it has only just entered the market, EasyCov is already arousing interest among professional athletes, and Asian and South American countries are lined up to purchase it. “With a rapid field test that is four to five times less expensive than those currently available, you can test passengers before they board a plane or ship, for example, or envisage the regular testing of staff in residential care homes.” Its deployment among general practitioners, or the future development of a self-test that can be performed at home, now depend on the framework that will be set by the health authorities.

- 1. CNRS / PMB ALCEN.