You are here

Neanderthals were artists too

Neanderthals (Homo neanderthalensis), a now extinct species who lived in Europe until about 40,000 years ago, were long depicted in prehistory textbooks as uncouth, weak-minded, a primitive version of Homo sapiens, capable only of ensuring their material survival and lacking any intellectual skills or interest in art. However, a meticulous analysis of engravings discovered in a cave in the Loire valley in France has now shown “unambiguously” that they were made by our distant cousins.1

“We have dated these rock engravings to over 57,000 years ago, making them the oldest ever found in France. By way of comparison, the ones discovered in the French caves of Lascaux and Chauvet are respectively 21,000 and 36,000 years old,” says Guillaume Guérin, a researcher in prehistoric archaeology at the Geosciences Rennes laboratory2 and co-author of this work. “These engravings are exceptional, and confirm that Neanderthals rivalled Homo sapiens when it comes to cultural skills,” says Jacques Jaubert, a prehistorian at the PACEA laboratory,3 and co-author of the finding.

A chance discovery

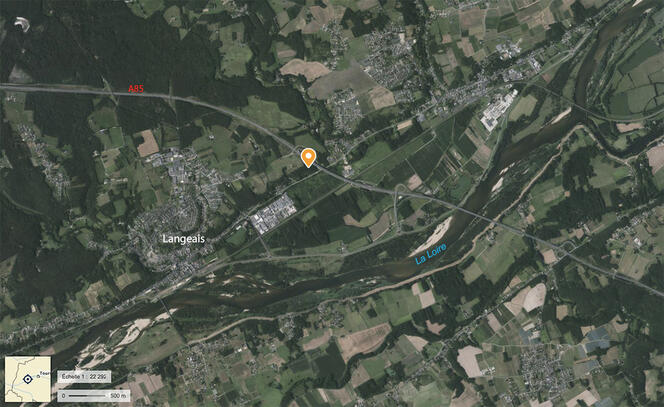

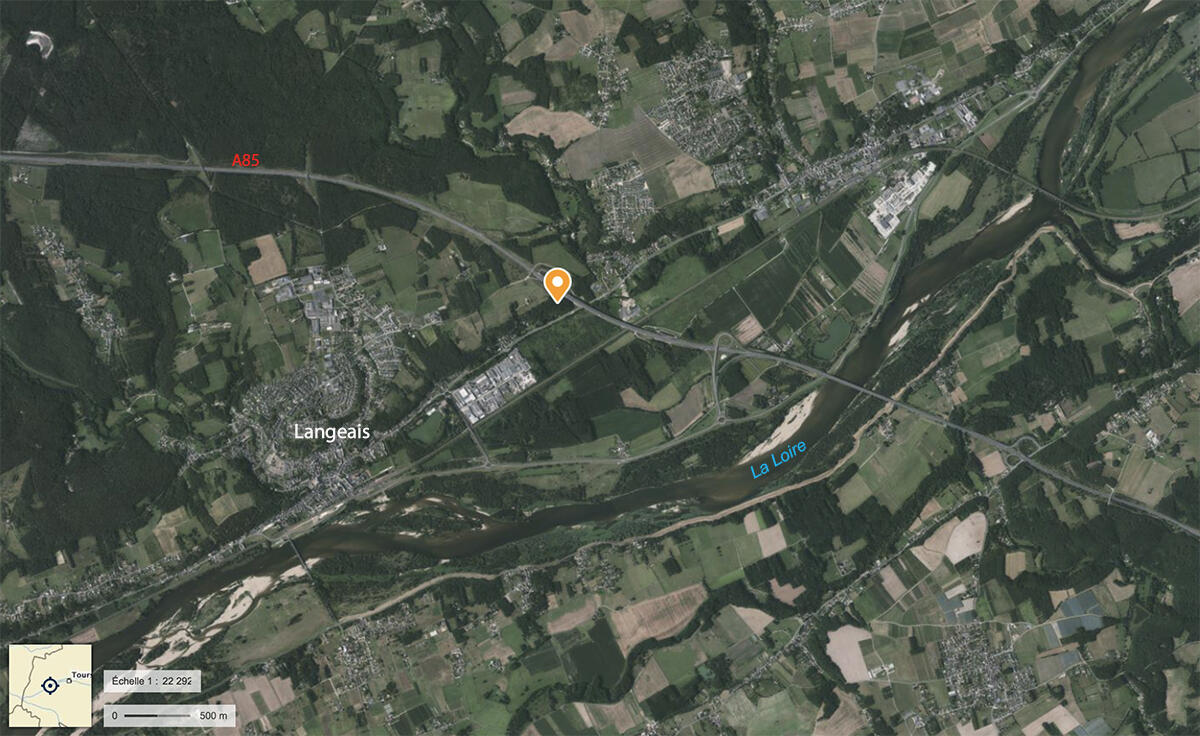

The engravings in question were found at the prehistoric site of La Roche-Cotard, in the Loire valley (central western France). The cave, which was listed as a historical monument in 2021, “might never have been discovered”, believes Jean-Claude Marquet, the coordinator of this recent work, and a visiting researcher at the LAT unit of the CITERES laboratory,4 and associate at the continental geohydrosystems (GEHCO) lab at Université de Tours.

This is because “the entrance to the cave, which is located on a hillside around 500 metres from the banks of the Loire, was long buried beneath 8 to 10 metres of sediment from the river and the plateau that overlooks it”.

However, in 1846, during the building of the railway line between Tours and Nantes, some 200 kilometres away, large amounts of sediment were extracted in the region, uncovering the entrance to the cave in the process. It was not until 1912 that François d'Achon, the owner of the park that was home to the cave, accidentally discovered it while searching for his dog, who had run into it.

When he excavated it, he discovered a succession of four chambers, as well as a multitude of bones from animals such as horses and bison, and around a hundred flint objects, including scrapers, points, and blades. Described in a short article in 1913,5 “the objects – which have unfortunately all been lost – were used to date the cave to the Neanderthal period”, Marquet explains.

Astonishingly, the 1913 paper made no mention of the engravings. It was not until 1976 that the archaeologist, who had learned about the existence of the cave,6 spotted them while directing new excavations there. However, for lack of a suitable dating technique and called away on other projects, he decided in 1978 to suspend exploration of the site, where he only resumed work thirty years later.

In 2015, he enlisted the help of around thirty French and European specialists in a wide range of disciplines such as cave art, geochronology, and geomorphology, with one precise aim in mind: to analyse, record and date the engravings.

“Undeniably intentional” creations

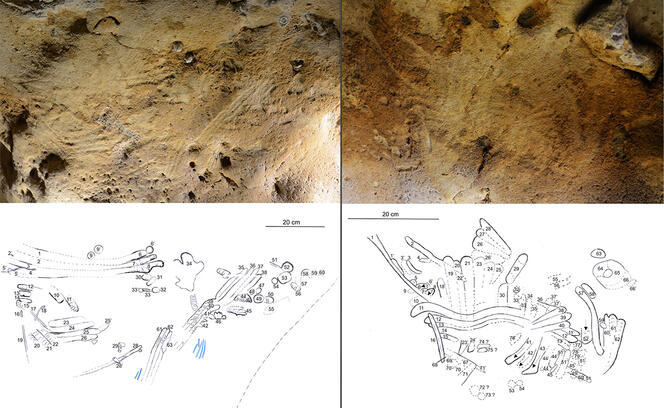

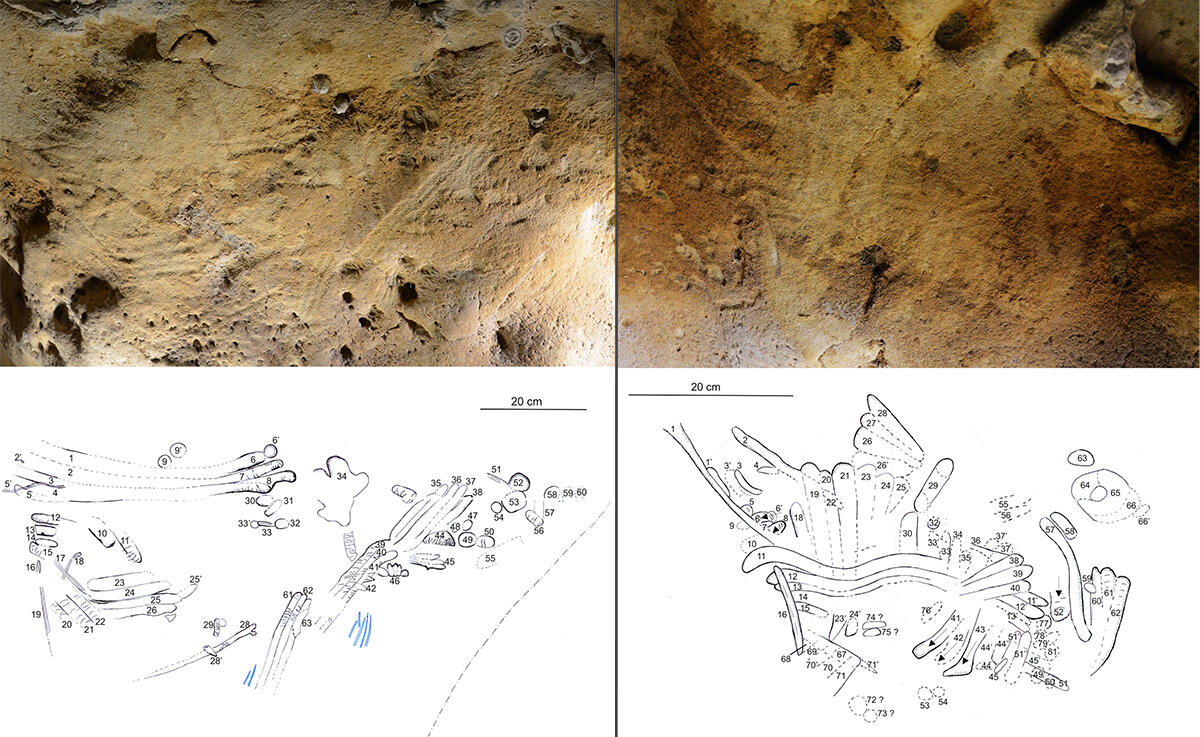

“Ever since the cave was opened in 1912, the outside air and the condensation-corrosion process have threatened the integrity of these traces,” Marquet explains. “So it was essential to describe and record them in order to preserve as accurate a record as possible.” To do so, the researchers used a multitude of techniques, including photography, high-resolution photogrammetry to digitally make a 3D reconstruction of each engraving, and reflectance transformation imaging to reveal features invisible to the naked eye.

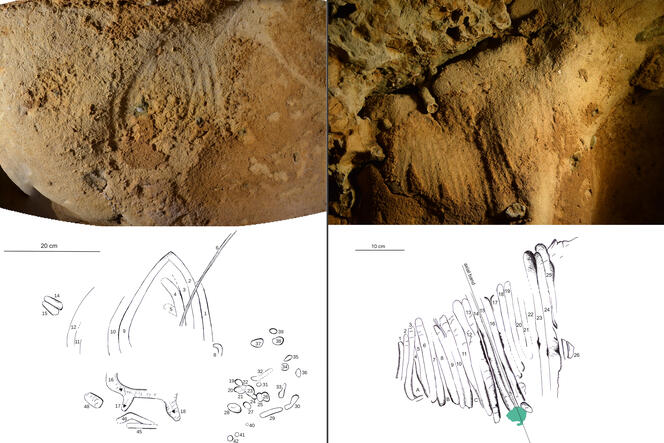

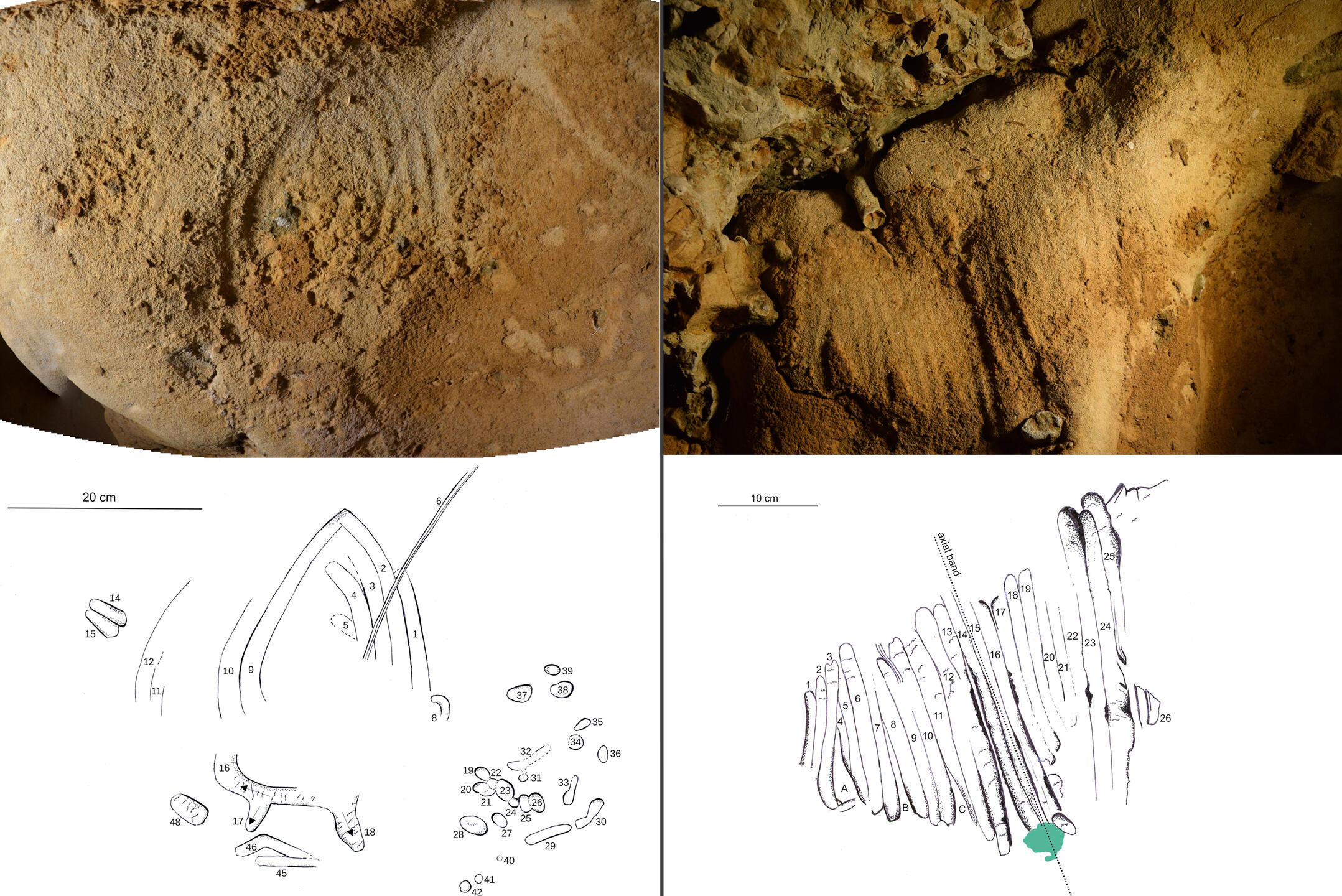

All in all, the team identified no fewer than eight panels, all located in the third room of the cave on the upper part of the wall, which is covered with a thin, brownish layer of chemically altered material.

As shown by an analysis of the geometry of the traces and by reproduction experiments on the wall of a neighbouring cavity, almost all the engravings were probably made with the finger. With one exception: “the ‘Rectangular Panel’, so named because it was carved on a rectangular-shaped projection of the wall, appears to have been done using a tool, possibly made of flint,” Marquet says.

The traces that are visible on entering the third chamber appear to succeed one another across the entire wall, ranging from the simplest to the most elaborate. Three of the panels stand out due to their more structured composition: the Wavy Panel, which includes – among other things – two long, undulating longitudinal tracings; the Circular Panel, the central part of which consists of curved traces forming an ogive; and the Triangular Panel, containing 25 parallel grooves. “The attention that appears to have been paid to the location, succession and layout of these engravings bears witness to an undeniably intentional creative process,” Marquet believes.

Optically Stimulated Luminescence dating

To date the engravings, the researchers were faced with a major obstacle. “None of the techniques normally available can be used on these tracings,” explains Guérin, who contributed to this part of the study. For instance, “Carbon-14 dating can only be applied to objects that were once living, such as bone and wood, while uranium-thorium dating , can only date engravings covered with a layer of calcite, and so on.” The researchers therefore had to take a roundabout way.

The team's starting point was based on a simple observation, namely that the discovery of flint tools in La Roche-Cotard indicates that, after it was occupied by prehistoric humans, the cavity was sealed off by sediments until the first excavations in the early twentieth century. Hence the experts’ decision to date the age of the cave's closure so as to get an approximate idea of the period when the engravings were made. Yet one question remained: couldn't the tracings be posterior to the opening of the cave in 1912? The researchers therefore compared them with other traces on the cave wall that were known to date from the 20th century, including marks made by excavation tools. They did this in particular by analysing the colours of the two types of tracing using an archaeologist's colour chart and a physical technique (a CM-600d spectrophotometer). Their idea paid off: “Our results show that the engravings are clearly not the work of Homo sapiens,” Marquet says.

In practice, to date the closure of the cave, the scientists collected 50 samples of the sediments that had blocked up the entrance. They analysed them using Optically Stimulated Luminescence (OSL) dating, which can determine the time when an object was buried. “This technique makes use of defects in the crystalline structure of minerals such as the quartz and feldspar present in the sediments. When crystals are exposed to the natural radioactivity in the soil, which is what happens when they are buried, the defects can trap electrons (negatively charged elementary particles –Editor's note). When the crystals are exposed to light from a laser or a LED (hence the term ‘optically stimulated’), the trapped electrons are released, and emit a photon . The intensity of the light emitted is directly proportional to the quantity of trapped electrons. Measuring this luminescence therefore makes it possible to estimate the time during which the sample was in the soil,” Guérin explains.

Helping to rehabilitate the Neanderthals

In the end, OSL placed the closure of the entrance at around 57,000 years ago. Two age determinations carried out on the main layer of silt from the Loire river that contributed to the closure show that the engravings could date back even further, to around 75,000 years ago. At that time, Homo sapiens had not yet arrived in Western Europe, the most commonly accepted date for this event being 45,000 years ago, which is why the scientists have come to the conclusion that the traces in La Roche-Cotard can only be the work of Neanderthals. “We don't know what these lines meant, and that's not surprising, since they are non-figurative productions . However, they are unambiguous examples of Neanderthal abstract drawings,” Jaubert says.

In fact, over the past two decades several studies have shown that Neanderthals exhibited sophisticated behaviours that point to modern cognitive abilities. In particular, in late 2020,7 a European team that included Guérin showed, for the first time in Europe, that a Neanderthal child had been carefully buried by its relatives some 41,000 years ago at La Ferrassie, in the southwestern French region of Dordogne, providing evidence that such behaviour was not an innovation specific to our species. “In line with this type of research, our work on the engravings at La Roche-Cotard is playing its part in helping to rehabilitate the Neanderthals,” Jaubert concludes.

- 1. “The earliest unambiguous Neanderthal engravings on cave walls: La Roche-Cotard, Loire Valley, France”, J.-C. Marquet et al., PLOS ONE, 21 juin 2023. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0286568(link is external)

- 2. CNRS / Université de Rennes.

- 3. De la Préhistoire à l'Actuel: Culture, Environnement et Anthropologie (CNRS / Université de Bordeaux / Ministère de la Culture).

- 4. Cités, Territorires, Environnement et Société (CNRS / Université de Tours).

- 5. “La Préhistoire en Touraine”, Éditions Presses Universitaires François Rabelais, 2011.

- 6. Ludovic Slimak et al. Sci Adv. 11 February 2022. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abj9496.

- 7. A. Balzeau et al. Sci Rep. 9 December, 2020. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-77611-z.

Explore more

Author

A freelance science journalist for ten years, Kheira Bettayeb specializes in the fields of medicine, biology, neuroscience, zoology, astronomy, physics and technology. She writes primarily for prominent national (France) magazines.