You are here

How Real are False Memories?

How can our memory play tricks on us?

Pascal Roullet:1 We are often convinced that our memories are consistent with reality but in fact, this is not always the case. Our memory does not function like a video camera that faithfully records everything that happens to us. As explained very clearly in the documentary “I think I remember therefore I am mistaken,”2 the information stored in our brains may be exaggerated, distorted or transformed. Even worse, some of our memories are completely invented—we call these “false memories.”

What are false memories?

P.R.: They are memories that we feel are completely true, but which are in fact created through the integration of imagined elements into factual memories. On occasion, such memories may have serious consequences. In the US for instance, hundreds of children convinced of the authenticity of their memories falsely accused their parents of pedophilia or physical abuse. Such was the case of the George Franklin affair, a father who was condemned to life without parole in 1990 following accusations of his daughter Eileen. He was acquitted six years later when it was proved that the “memories” of his daughter, which were inconsistent with DNA analysis, were in fact a combination of real memories and stories she had read in the media.

How are such false memories generated?

P.R.: We are all potentially capable of creating false memories through autosuggestion, which involves convincing ourselves that we have actually undergone experiences that were in reality false; or as a result of suggestions or directed questions from figures who embody authority, such as psychotherapists or police officers. In her studies, American psychologist Elizabeth Loftus, a highly-respected false memory expert, always started out with elements taken from true memories—based on eyewitness accounts of those close to a subject, photos, details published in the media, etc.— before adding new, but completely false elements.

And in more concrete terms?

P.R.: For example, she showed students who had all visited Disneyland in their childhood the picture of an advertisement for the theme park that included an image of Bugs Bunny. The following week, when she questioned them about their experiences, 35% said they remembered seeing Bugs Bunny while in Disneyland… even though Bugs Bunny actually belongs to Disney’s rival, Warner Brothers… More recently, two English psychologists managed to convince over 50% of the students they tested that they had committed… armed robbery! They achieved this by integrating this false memory into a fictitious narrative studded with true facts about the volunteers obtained from their parents.

What are the brain processes involved for creating false memories?

P.R.: As was demonstrated in mice by an American research team in 2013, false memories are created by the simultaneous activation of two neuronal networks: one associated with true memories, and the other containing the traces of false memories. Activation of these two networks ultimately results in the creation of a single network through a particular mechanism of memorization known as reconsolidation.

What is it?

P.R.: Let's first understand that when information is memorized, it is stabilized in the brain over the course of the 8 to 12 hours following acquisition. This process is known as consolidation, and requires extensive synthesis of proteins that enable the creation both of new connections between neurons and of new neuronal networks, and so on. However, this stabilization process is not definitive: when consolidated information is reactivated through recall, the neuronal network bearing its traces once again becomes malleable. In order to become re-stabilized, the memory must undergo another cerebral process also requiring protein synthesis: reconsolidation. If during this phase, in which the memory is fragile once more, we are exposed to a false element, the latter is integrated into the preceding consolidated memory. And here, a false memory is guaranteed.

Is it possible to erase certain false memories by acting on this process of consolidation?

P.R.: Yes. And this opens up major therapeutic horizons for certain disorders involving debilitating memories, such as phobias and the kind of traumatic memories seen in post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), a phenomenon that affects 17% of victims of disturbing events (accidents, rape, terrorist attacks, etc.) and which causes them to relive the event over and over. Promising initial experiments on PTSD have shown that if administered during reconsolidation, propranolol (a drug used for over 30 years to treat migraine and heart disorders) effectively reduces the emotional content of the memories, leading to cure in 70% of treated patients.

Is it possible to strengthen some of our memories, for example to treat the memory disorders inherent to Alzheimer’s disease?

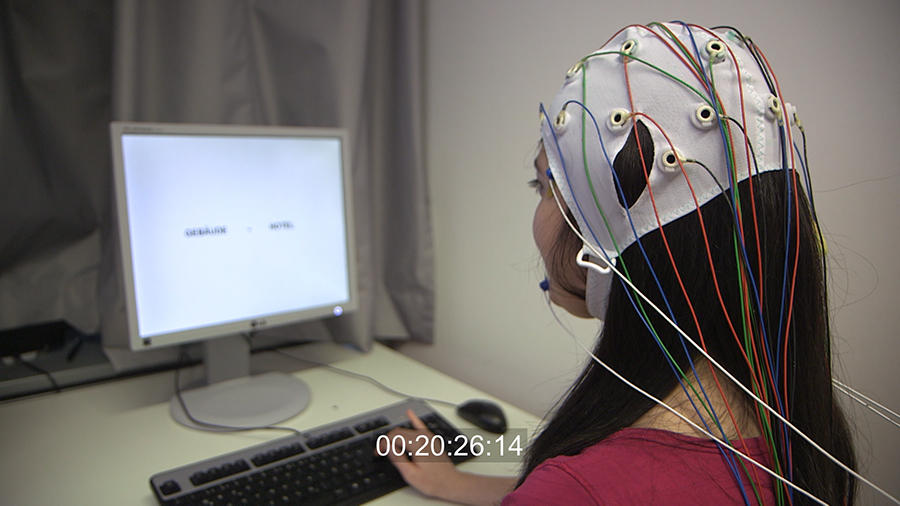

P.R.: Yes, this is also a possible avenue. For example, in 2013 a German research team showed that when volunteers were asked to memorize 80 word pairs before going to sleep, if specific sounds enabling artificial reinforcement of their brain waves were played to them during deep sleep, they remembered more word pairs (25 on average, versus 15 without reinforcement). Yet this experiment does not revolve around the modification of memories but rather concerns boosting the ability of memorization, which is in fact a different story.

- 1. Mécanismes neurobiologiques de la mémoire” (REMEMBeR) of the Centre de Recherche sur la Cognition Animale à Toulouse (CNRS / Université Paul Sabatier).

- 2. "Je me souviens donc je me trompe": http://www.arte.tv/guide/fr/064443-000-A/je-me-souviens-donc-je-me-trompe