You are here

When phytoplankton kills

Throughout the year 2020, over a thousand fishermen in Senegal were affected by a mysterious illness that caused severe acute dermatitis, characterised by inflammation and skin lesions, leading to considerable concern in the international community. Following a fresh outbreak in 2021, several scientific studies attempted to identify the causes, and the culprit was finally revealed in a paper published in early 20251. It turned out to be neither a bacterium nor an environmental pollutant but rather a tiny marine microalga, Vulcanodinium rugosum, which expresses a toxin called Portimin A that causes skin necrosis in humans.

Léana Gorse, a PhD student at the Institute of Pharmacology and Structural Biology (IPBS)2 and lead author of the study, explains the origin of the outbreak: "V. rugosum lodges in the fishermen's driftnets, where it becomes highly concentrated. When they handle their nets, they come into direct contact with the toxin, especially via their hands and eyes."

The episode is all the more worrying as it is far from being isolated. Cases of environmental toxins being released by microalgae are becoming increasingly frequent around the world.

In fact, this is what enabled Gorse and her colleagues to find an explanation for the outbreak that affected Senegal: "It all began with a misunderstanding. At the time, we were investigating another microalga on the Basque coast, where beaches were being closed every summer due to its proliferation. To better understand it, we contacted Philipp Hess, a colleague at IFREMER who specialises in the subject, and he provided us with samples of unknown toxins, some of which came from Senegalese boats. Together with Hess, we then compared these toxins to others produced by V. rugosum from Cienfuegos Bay, Cuba, where 60 bathers had suffered similar skin irritations a few years earlier. The toxin profiles matched perfectly."

The blues of blooms

All these microalgae, which, together with cyanobacteria, make up the phytoplankton, can form what are known as algal blooms. In the spring and summer – and even over a period of up to a year, in the case of Senegal – these aquatic species take advantage of optimal environmental conditions to multiply.

Although this is a natural phenomenon, its severity and the surge in harmful species in recent years are causing concern among scientists. In addition to their toxicity, the uncontrolled proliferation of certain species leads to the formation of an organic layer on the surface of the water that blocks out all light. Moreover, their biological decomposition causes a decrease in available oxygen, leaving a dead zone with very low oxygen levels in the aftermath.

Éric Fouilland, a CNRS senior researcher at the Marine Biodiversity, Exploitation and Conservation Unit (MARBEC)3, who studies, among other things, the ecology of toxic and non-toxic phytoplankton along the Mediterranean coastline, outlines the factors conducive to blooms: "The primary element is the massive presence of human-induced inorganic nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus, due to agriculture, industry and urban wastewater. The severity of the blooms is directly proportional to the amount of nutrients available."

A bloom therefore lasts until all the available nutrients have been completely used up. "The second factor is water temperature. These single-cell organisms thrive in temperatures of around 20-25 °C. And now, with water becoming warmer due to climate change, algae are flourishing increasingly early in the year," laments this microalga specialist.

Residence time

While algal blooms are pretty harmful in the sea, they can actually cause mass extinctions in lakes. In these confined environments, a third factor comes into play, in addition to higher nutrient concentrations and temperatures: residence time, i.e. the time it takes for water to be renewed. In the open sea, water is regularly replaced by the tides. However, "in lakes, residence time in summer becomes almost infinite", points out Alexandrine Pannard, a senior lecturer in the ecosystems, biodiversity, and evolution laboratory (ECOBIO) at the Université de Rennes4 in northwestern France.

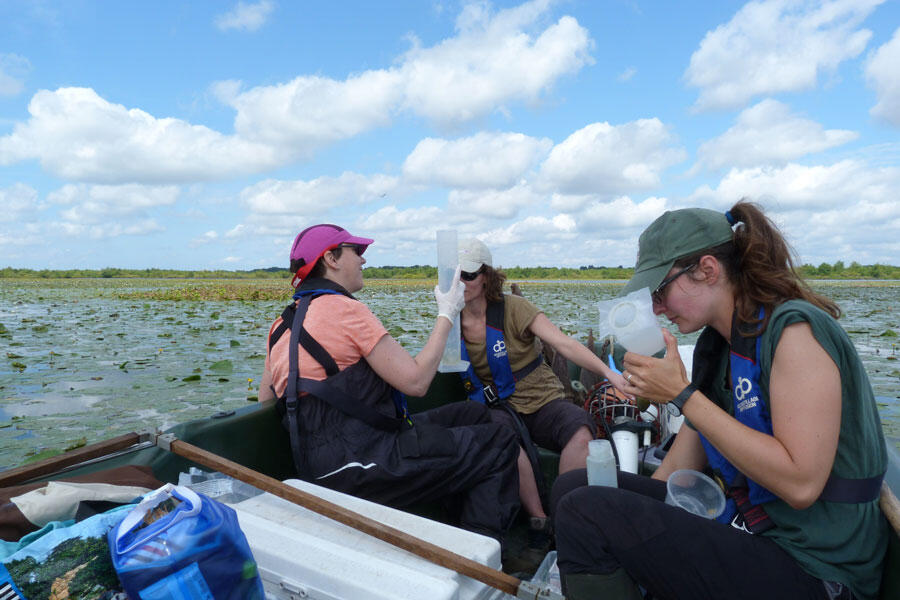

An expert in freshwater phytoplankton, she closely monitored the Lac de Grand-Lieu, a lake located in a nature reserve near Nantes (western France), for two years. The aim of her scientific project was to characterise, quantify and analyse the distribution of phytoplankton species in France's largest lowland lake (in winter), covering an area of 63 km².

As soon as she arrived, Pannard noticed that the Lac de Grand-Lieu boasted an unusual feature: the western third of the lake, which is sheltered from the wind, is home to a huge number of water lilies. By providing shade below the surface, they lower the temperature of the water by as much as 9 °C, as compared to that of open water, which can reach over 30 °C in summer.

The only organisms that thrive at such high heat are cyanobacteria, and as a result, repeated algal blooms affect two thirds of the lake every year, almost certainly leading to a massive decline in biodiversity. By contrast, in the water shaded by water lilies, all the other species of phytoplankton are doing very well. In other words, as Pannard explains, "if the lake loses its water lilies, which are currently showing signs of decline, it will lose another third of its biodiversity".

Blooming blooms

The human activities that define the Anthropocene epoch – especially intensive agriculture and industry – are playing a major role in the proliferation of algal blooms. Pannard points out that "the blooms are the result of anthropogenic activity on the banks of lakes and waterways". This is why lakes in Africa and Australia, where the effects of such activity are exacerbated by higher temperatures, are being impacted by blooms, whereas the cold, sparsely inhabited forest regions of Canada are spared.

At sea, international shipping also helps to spread microalgae beyond their usual habitats. This was one of the conclusions of the study on the disease affecting Senegalese fishermen. Étienne Meunier, a CNRS senior researcher at the IPBS, points to the role of ocean-going vessels in the transportation and dispersion of microalgae such as the Mediterranean species Vulcanodinium rugosum, recently enabling it to colonise open seas like those off the coast of Senegal.

Lastly, cyanobacteria produce dormant cells that build up in sediments after a bloom and can survive for several thousand years, until the warm temperatures in which they thrive return. "Today, we are paying the price for global warming," Pannard warns. "Even though there has been a reduction in nutrient inputs over the last thirty years or so, rising temperatures are causing more and more blooms."

As the Senegalese episode shows, humans are already being affected, with sometimes indirect health impacts. "In the absence of oxygen, some bacteria break down sulfate, a chemical compound naturally present in seawater, releasing hydrogen sulfide, which is foul-smelling, and even toxic at high levels," says Fouilland.

He also mentions the case of oysters which, "when contaminated with toxins from phytoplankton, even though they themselves may not necessarily be harmed, can cause poisoning in humans when consumed".

These health effects go hand in hand with economic losses. In Australia, algal blooms in lakes are decimating entire herds of livestock that drink water from them. In France, the partial closure of beaches on the Basque coast at the peak of the summer season is affecting local tourism. As for Senegal, Meunier points out that "the fishermen, who are highly dependent on their activity, were severely struck by the closure of certain marine areas while the bloom lasted".

Preventing algal blooms

How then can we protect ourselves against the increasingly harmful effects of ever more frequent blooms? On a practical level, Pannard advocates filling shallow lakes, mostly created for recreational purposes (primarily fishing), as they are difficult to restore after a bloom, making it necessary to either remove the sediment or drain off all the water. She believes that "a network of very small ponds one or two metres wide, better protected from the effects of algal proliferation, is more resilient than murky lakes silted up by a series of blooms".

With regard to seas and oceans, Fouilland calls for a reduction in urban development and anthropogenic pressure along coastlines, although there is a downside: "To prevent an excess of algal blooms, we should stop discharging nutrients into the sea. However, this will deplete the marine environment, and inevitably impact the productivity of fisheries and aquaculture, since phytoplankton lie at the base of the ocean's food chains."

A solution might however emerge from an unexpected quarter. The study which Gorse and Meunier took part in highlighted the fact that part of the population – including some Senegalese fishermen – carried a genetic mutation making them resistant to Portimin A, the harmful toxin released by the Vulcanodinium rugosum killer algae.

Gorse sees a glimmer of hope: "It's a form of human adaptation to this new environmental pressure." In the future, mutations selected by the climatic and microbial environment might perhaps make us more resistant to increasingly severe attacks.

See also

Comprendre le phénomène des marées vertes (in French)

Océans, que reste-t-il à découvrir ? (in French)

La dégradation des algues, enjeu majeur du cycle du carbone (in French)