You are here

Understanding vertigo

Vertigo is a relatively common condition, where patients have the feeling that their body is in motion or everything is spinning around them. However, it can be very disabling when it becomes chronic. Nearly 300,000 people in France are affected by these disorders, which are often caused by damage to the vestibular system.

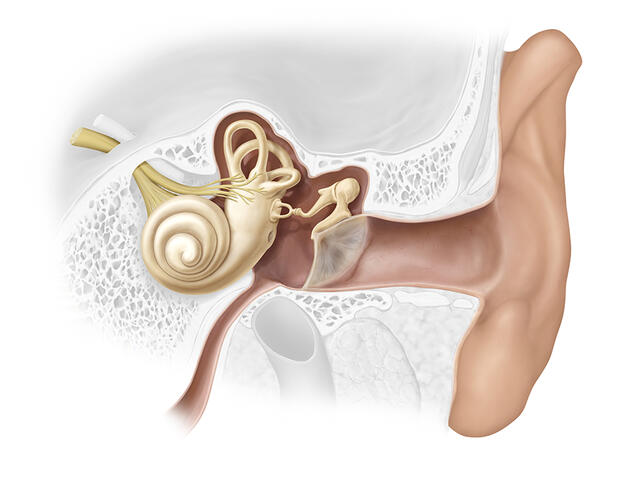

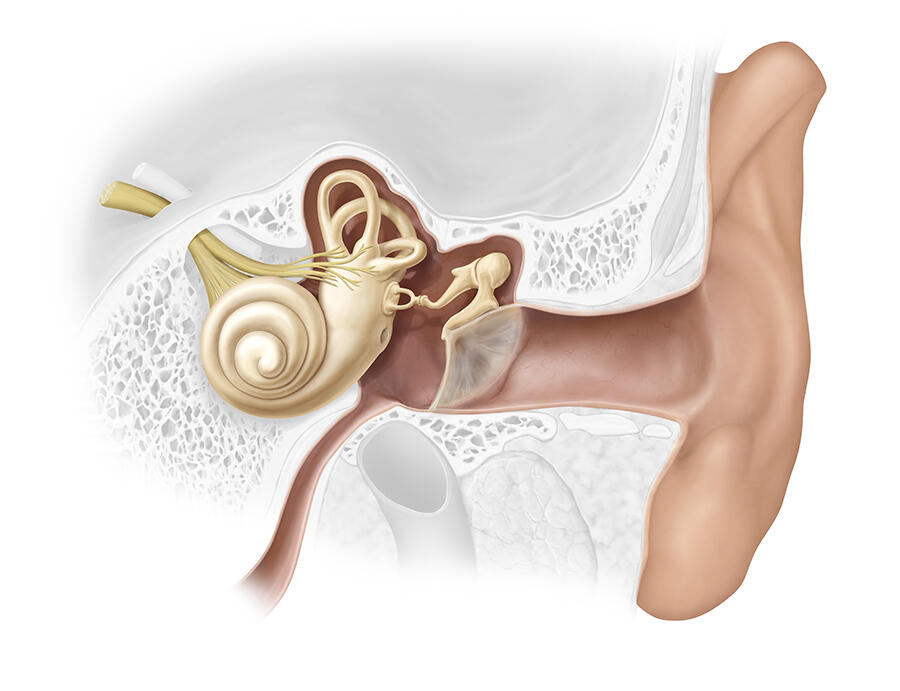

Lodged in the inner ear and protected by a very thick bony carapace (the temporal bone), the vestibular system is a highly sensitive and highly perfected sensory system. It informs the brain of all micro-movements and micro-accelerations of the head. It encodes different parameters, such as the amplitude and frequency of movements. These binary codes are then transmitted via vestibular nerve fibres to the cerebral trunk, cerebellum and brain where the information is used for a broad range of functions, including postural reflexes and balance, as well as gaze stabilisation, or orientation and perception of the body in space.

An illusion of body movement

This suggests that in this case, vertigo does not only mean fleeting dizziness or the feeling that the ground gives way under our feet when looking down into an empty space. “Strictly speaking, vertigo is an illusion of movement of the body and/or the environment around you. It gives the impression that the body, or objects around it, are spinning, moving or shifting,” explains Christophe Lopez, a neuroscientist in the Laboratory of Cognitive Neuroscience (LNC)1 and scientific coordinator of the Vestiself project supported by the French National Research Agency, which is studying the links between the vestibular system and body awareness. “There are several types of illusory movement: a spinning sensation similar to being on a merry-go-round, or a feeling of translation that can give patients the impression they are falling or floating in a room”, he adds.

Christian Chabbert, LNC researcher and founder of the Vertige research group, emphasises that other disorders are frequently associated, thus hampering everyday life: “Someone with vertigo may experience loss of balance, falls and loss of spatial memory.” Christophe Lopez also explains that “the vestibular system is not solely involved in actions that are in fact reflexes, such as standing up. It also plays a part in much more complicated situations, and affects representations of space, the body and sense of self. And because it enables coding of the body’s orientation and gives us sensory information so that we can locate ourselves in space, memorise journeys, etc., it contributes to spatial navigation in general”.

The neuroscientist points out that “the vestibular system also produces information that allows a representation of the body, its size, length or volume. Astronauts who live under weightless conditions in space, lose the gravity-related functions of their inner ear, and may have the impression that their body is longer or shorter than it actually is” .

Such phenomena are seen in the clinic: when the vestibular system is dysfunctional, the inner ear will tell the brain that things are turning, while other sensory sensors (sight, touch, etc.) “state” the contrary. The way in which people experience their bodies is therefore affected. For example, they may have the feeling that their neck is lengthening. They may also be faced with mixed reference points, become disoriented and no longer be able to tell top from bottom or left from right.

Psychiatric and hormonal comorbidities

These sensory disturbances are often seen in conjunction with dizziness and nausea, as well as difficulties fixing the gaze during movement. “Vertigo is a type of invisible disability which causes considerable distress to sufferers,” comments Christophe Lopez. This has been borne out by recent studies that have demonstrated the intimate links between vertigo/vestibular disorders and mental health.

“Anxiety and vertigo are very closely linked. Firstly, people with vertigo may develop anxio-depressive syndrome, particularly when they start to worry about going out, not wishing to be seen as they stumble or fall if an episode occurs in the street. Secondly, the symptoms of anxio-depressive syndromes may include vertigo, instability, etc.” explains Christophe Lopez.

“We have been able to document the link between consulting for vertigo and suffering from psychiatric comorbidities. For example, as well as having a greater chance of being afflicted with anxio-depressive syndrome, those who seek medical advice are more likely than others to have a higher score for depersonalisation, which is a dissociative disorder. So there is a combination of both psychological and otoneurological factors.” These recent discoveries are reassuring for patients who have long been classified as “psychiatric”, even though their problems are the result of a sensory disorder.

The intricate relationships between the vestibular system and the rest of the body are indeed far from just affecting mental health. “Studies have recently demonstrated that the vestibular system is also involved in regulating the hormonal system, bone density, food intake and sleep,” explains Christian Chabbert, who is actually working on hormonal issues. “Our team has observed a comorbidity between vertigo and altered hormonal status (notably during the premenstrual period, in early pregnancy or during the premenopause) as well as diabetes and hypothyroidism,” reveals the scientist.

“Quite surprisingly, we have discovered the presence of hormone receptors in the inner ear. One current area of research aims to elucidate the relationships between vertigo and hormones. We are starting a multicentre clinical study designed to identify the blood biomarkers associated with acute episodes of vertigo, which may in the future improve the diagnosis of this condition and its causes. During the study, hormone assays will be performed in patients during an episode and then a month later.”

A clearer understanding of the links between vertigo and the menopause, or between vertigo and diabetes, will help to improve the way patients are managed through the introduction of targeted solutions.

From identifying the causes to rehabilitation

Today, the management of patients remains lengthy and not always satisfactory. “Obviously, the treatment of vertigo depends first and foremost on its causes,” explains Pierre Denise, hospital practitioner at the CHU University Hospital of Caen (northwestern France), a physiopathologist specialising in balance and vertigo. And it is clear that these causes are numerous: “Vertigo can be triggered by all sorts of damage affecting sensors in the inner ear, the vestibular nerve and/or many regions of the brain that process information coming from the inner ear,” details Christophe Lopez.

This damage may be due to a variety of factors: a mini-stroke affecting the inner ear or vestibular regions; Menière’s disease – which corresponds to changes in the pressure of the fluids within the inner ear; neuritis – an inflammation of the vestibular nerve caused by a viral infection; a tumour on the vestibular nerve (neurinoma); a stroke; epilepsy or trauma (e.g. a fall causing a fracture to the bone surrounding the inner ear).

To this long list should be added the ingestion of so-called “ototoxic” substances that are found in certain pharmaceutical products such as antibiotics or anti-tumour agents, foods such as manioc, or even alcohol: “When consumed excessively, alcohol can give the impression that the the world is spinning around you. Indeed, it acts directly in the inner ear where it modifies the properties of the fluids it contains,” notes Christophe Lopez.

In many cases though, treating or removing the cause is not enough to alleviate the vertigo. “If the cause has been treated but recovery is insufficient and the vertigo persists, vestibular rehabilitation by a specialised physiotherapist remains the treatment of choice,” explains Pierre Denise. During rehabilitation, “the patient’s central nervous system is reorganised in order to recover its balance capacities based on other sensory modalities: proprioception, vision, skin sensitivity, or visceroception” , he adds. “For example, it involves the use of a rotating armchair or visual stimulations.”

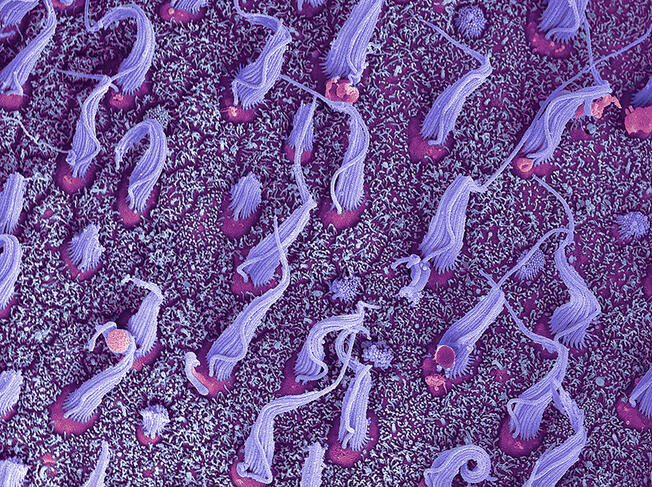

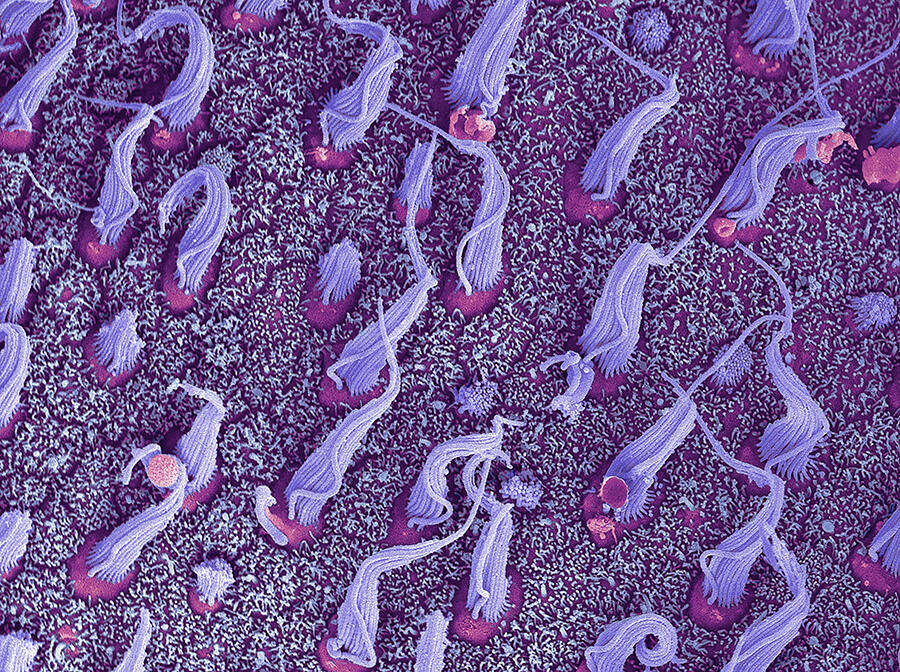

Pierre Denise points out that “there are also other very recent therapies that include methods to help the regeneration of sensory cells in the vestibular system – ciliated cells – when these have been damaged”. For his part, Christophe Lopez indicates that “some people may find it helpful to consult, particularly since psychiatrists have developed some behavioural and cognitive therapy techniques which appear to be useful in some patients”.

Clues from astronauts

Studying how the a lack of gravity affects the vestibular system of astronauts living under weightless conditions offers another recent lead for improving the management of patients with vertigo of vestibular origin, as well as those suffering from bilateral vestibulopathy – i.e. vestibular damage on both sides. “These patients do not suffer from vertigo but from a lack of balance when walking, particularly in the dark, with their eyes closed or when rising from/walking on uneven, soft or precarious ground. They are also affected by oscillopsia resulting from ocular instability associated with head movements. To these characteristic symptoms should be added sleep, orientation or memory disorders and anxiety,” Pierre Denise explains.

Through a citizen science approach, the physiologist and his team are collaborating with the AFVB French idiopathic bilateral vestibulopathy association in order to better understand this pathology and to evaluate the efficacy of manoeuvres and training to improve symptoms. “We also hope that what we have learned from astronauts might serve to improve the management of sufferers,” he concludes. Who knows whether new treatments for vertigo and balance disorders of vestibular origin won’t one day come from the stars? ♦

- 1. CNRS / Aix-Marseille Université.