You are here

Memorising the passing of time

In human cognition, episodic memory is the conscious memory that allows us to recall past events, or what we refer to as “recollections”. It answers the questions “what”, “with whom”, “where” and “when”, and thus places these recollections within a temporality. It is the neurobiological foundations of this episodic memory that the team at the Brain and Cognition Research Centre (CERCO)1 investigated, in collaboration with the Netherlands Institute for Neuroscience. The scientists focused in particular on the following question: does the human brain contain neurons that process time-related information, like those found in the hippocampus of rodents?

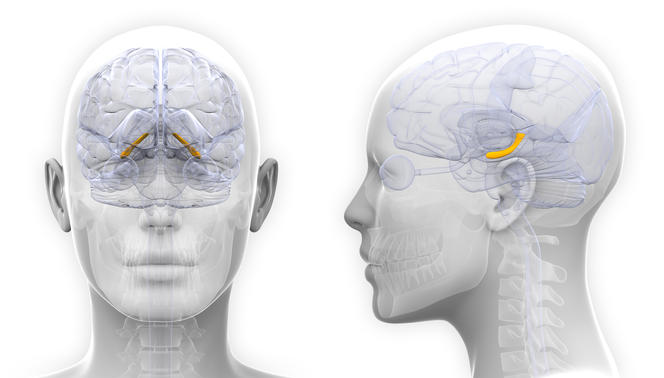

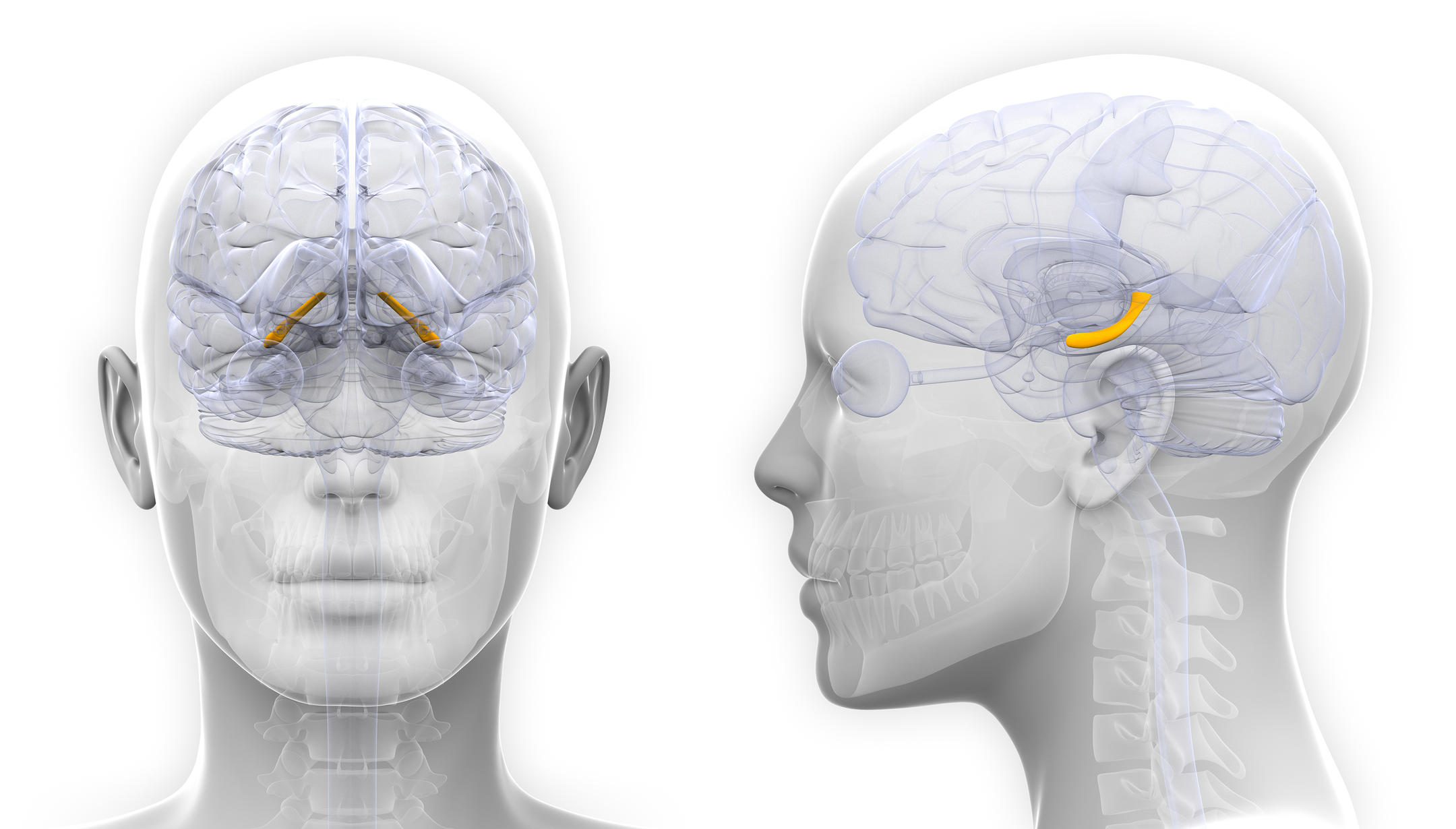

The hippocampus deciphered

The hippocampus is a brain region that belongs to the limbic system, the structure that manages most human behaviours and emotions. It is also involved in the formation of long-term memory, and the spatial memory used for orientation. It is actually one of the first structures to be impacted by Alzheimer’s disease, thus explaining the memory and orientation disorders affecting these patients.

The first link between it and memory was established in the mid-20th century when a neurosurgeon and a professor of neurology removed the hippocampus from an individual suffering from severe epilepsy. However, following the surgical procedure, the patient was affected by a new disorder: selective amnesia. He was no longer able to create new memories and had lost the most recent.

Neurobiological studies conducted in rodents subsequently showed that some neurons in the hippocampus deal specifically with time-related information and particularly with changes to situation over time. These neurons function throughout a given action, thus encoding its duration. Other studies also established that rodents with lesions affecting the hippocampus were unable to succeed in completing tasks that required them to remember the order in which they had smelt particular odours.

Understanding human temporal memory

Memorising past events entails establishing a temporal connection between the specific actions of an experience. The brain must thus accurately represent the order of events as a function of the time that has elapsed. The neurons that analyse time in the hippocampus may thus play a crucial role in this temporal organisation of human memory.

In order to have a better insight into the involvement of the human hippocampus in temporal memorisation, the neurobiologist Leila Reddy and her colleagues at the CERCO carried out two experiments at Amsterdam University Medical Center. They called on patients with severe epilepsy and in whose brains doctors had implanted electrodes in preparation for a neurosurgical procedure. “To carry out these experiments, we needed to record data from isolated neurons in the human brain, which requires electrodes to have been implanted in the brain to record neuronal activity,” the researcher explains. “This is a very invasive procedure which, for obvious ethical reasons, we could never have conducted in humans just for the purposes of our study. The subjects we selected were therefore patients in whom electrodes had previously been implanted for strictly medical reasons.”

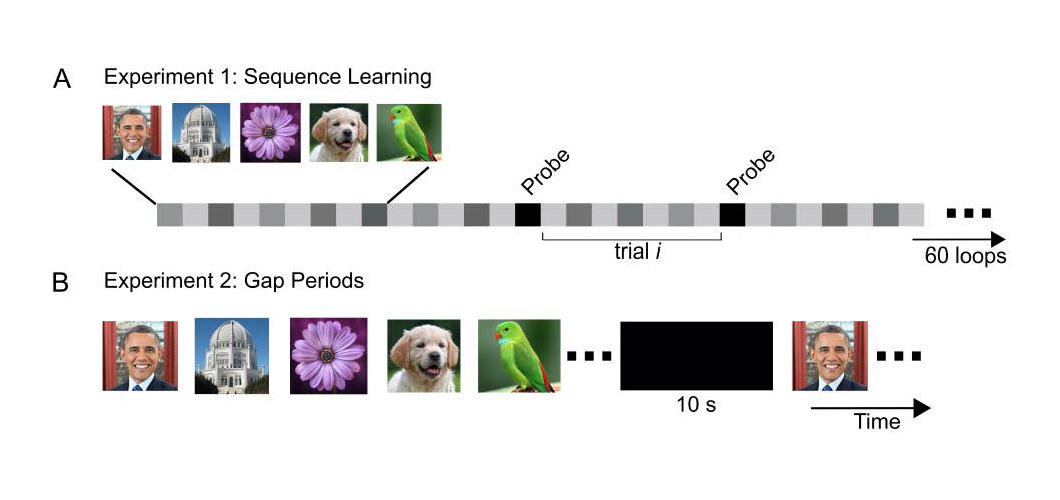

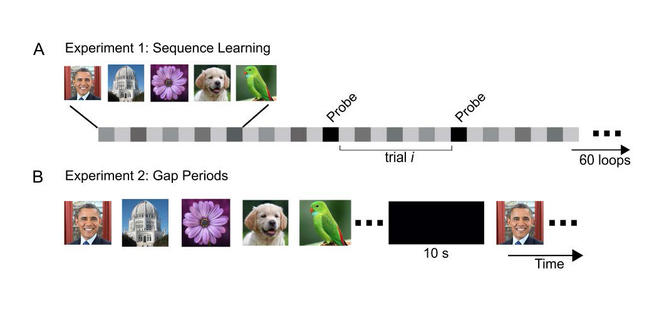

During the first experiment, participants were asked to watch a screen projecting a series of images they had to memorise, together with the order of their appearance. The second experiment, performed in different patients, was identical except that between two series of images, the research team inserted a black screen for a short period. The aim was to determine which neurons were activated individually during these intervals devoid of temporal information. The specific activities of 429 neurons in the hippocampus were thus recorded during the first trial, as opposed to 96 neurons during the second.

The results confirmed the presence of so-called “temporal” neurons in the human hippocampus. During the two experimental sessions, the activity of around 30% of the hippocampal neurons was modulated by time during the learning period of the sequence (128 out of 429 neurons in experiment 1 and 26 out of 96 during experiment 2). The second test showed that these neurons could also encode time in the absence of temporal information. While 13 temporal neurons were only activated when presented with an image (learning phase), three continued to be active when the black screen was shown. Thus the number and type of temporal neurons mobilised varied according to the demands of the task.

Hippocampal neurons therefore possess considerable flexibility in terms of their operating mode. “We do indeed know that some of these neurons are able to encode other dimensions of our actions, such as place or time, etc., but we do not yet know how they operate. This remains an open question which might be answered by studying a larger number of neurons, notably in a healthy brain,” notes Reddy. “Nevertheless, the discovery of temporal neurons in the human brain constitutes a major advance in our understanding of the perception of time.”

- 1. CNRS / Université Toulouse III - Paul Sabatier.