You are here

Making Sense of the Sense of Smell

When paying attention to the odors around us, we sometimes find ourselves flooded with memories and sensations. Nearly everyone has experienced that feeling, which can be quite intense. Behind the images and sounds that we perceive, a complex neurobiological process is at play: the transformation of a molecule into an emotional response.

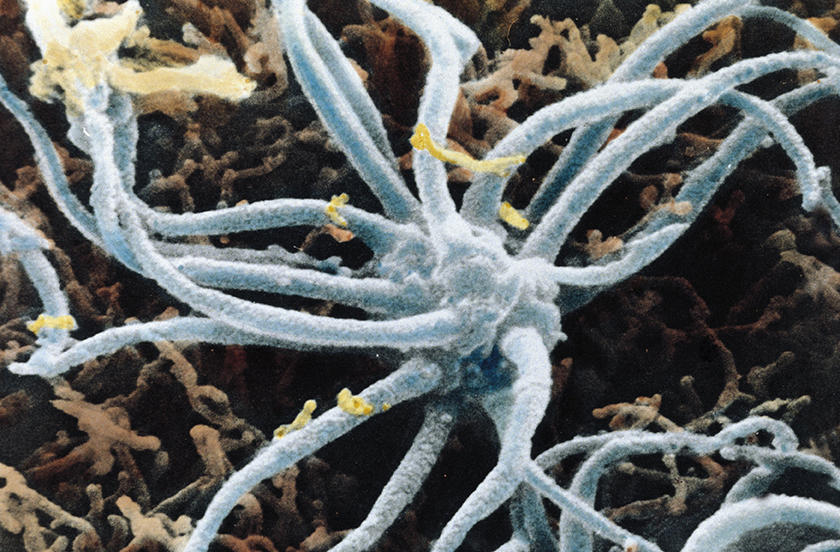

The source of any olfactory stimulus is a compound volatile enough to travel through the air and hydrophilic enough to penetrate the mucus of the nasal cavity, where it can be detected by the neuronal cilia. While colors are transcoded by three types of so-called “cone” receptor cells in the retina, odors are captured by no fewer than 400 receptors in the neurons at the back of the nasal cavity. And since one receptor can recognize several molecules and one molecule can activate several receptors, the possible combinations are nearly endless.

“Detecting an odor is like distinguishing a musical chord played on an organ with 400 keys,” explains Jérôme Golebiowski, a professor at the ICN1 and co-director of the GDR O3 Odorants- Scents-Olfaction transdisciplinary research group. “The olfactory system is so wonderfully complex that the number of possible ‘chords’ is virtually infinite.”

A mental representation

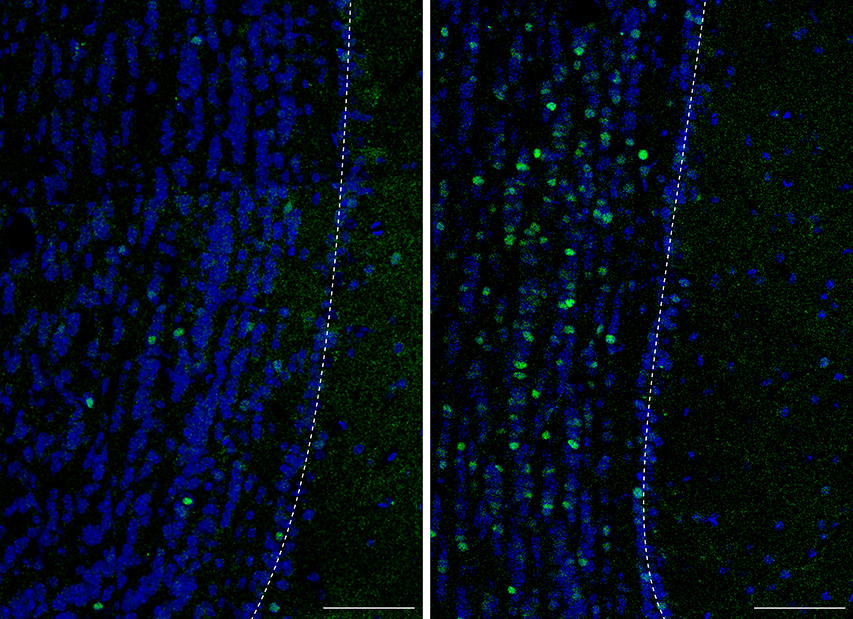

It takes a brain for a molecule to become an odor. According to Pierre-Marie Lledo, co-director of the Genes, Synapses and Cognition laboratory,2 the human brain creates olfactory “maps” based on the combination of receptors activated by a given molecule. These maps serve as a kind of QR code that allows us to associate each chemical stimulus with a mental representation, i.e. an odor. This representation is malleable and can evolve depending on each individual’s experience and culture.

As Golebiowski points out, “The first thing that we perceive in an odor, before any rational response, is its emotional aspect: I like it or I don't like it.” Odors can awaken such clear, intense memories and feelings because they activate parts of the brain that are closely related to the regions involved in emotions: the orbitofrontal cortex, which is associated with decision-making and reward-seeking, and the amygdala, which plays a role in functions like fear, pleasure and memory.

Certain reactions to odors are a matter of survival and have probably been selected by evolution, for example to prevent us from eating spoiled food. “Bad odors are correlated with a particular type of receptors that detect amine compounds like putrescine and cadaverine, which are present in decomposing organic matter,” Golebiowski adds. “These receptors are hard-wired with our aversion mechanisms.”

Yet the repellant or attractive nature of certain odors can also arise from cultural conditioning. One example is preserved eggs, a Chinese delicacy that smells “rotten” to Westerners, whereas most Asians are disgusted by the smell of ripe Camembert cheese.

Sniffing out diseases

Odors have been recognized as possible indicators of danger or pathologies since ancient times. In the 5th century BC, Hippocrates noted how body odors could be modified by various diseases, a phenomenon that allows physicians to use their sense of smell as a diagnostic tool. Breath that smells like rotten eggs can be indicative of diabetes or a liver disorder. Some people are even sensitive to the smell of Parkinson’s disease. In fact, illness-related exhalations may precede clinical symptoms by several years, constituting a faint early signal that can nonetheless enable a diagnosis. Since early treatment is crucial for pathologies like cancer and Alzheimer’s, researchers are taking an increasing interest in odors.

When the human sense of smell is not keen enough, doctors have been relying on animals—with most encouraging results. In February 2017, a team from the Institut Curie presented the findings of “KDog” (link is external), a project aimed at testing the effectiveness of breast cancer screening using sniffer dogs. After six months of training, two Belgian shepherds “analyzed” a panel of 130 women volunteers, with asuccess rate of 100%!

Artificial noses

The next challenge for olfactory researchers is to perfect an electronic nose than can emulate the performance of an animal nose. In 2015, an Israeli company released the Sniffphone, a smartphone-linked device able to detect early-stage cancer by analyzing a patient’s breath. Other projects aim to create multipurpose electronic noses to identify a wide range of odors in complex mixtures. Potential applications range from the food industry to security to the detection of atmospheric pollutants.

Researchers at the ICN are studying how the olfactory system encodes chemical stimuli and interprets them as odors. The laboratory has developed a computerized nose, a bio-inspired digital simulation conceived to reproduce the behavior of 400 olfactory neurons. Virtual molecules are introduced into the system, which categorizes them as odors. “In terms of the diversity of olfactory receptors, everyone is different,” Golebiowski says. “We hope that our digital nose will allow us to understand how the brains of two individuals can generate a common representation of an odor while receiving different signals from the receptors. The ultimate goal is to predict the odor of a molecule based on its structure.”

Explore more

Author

Holding degrees from both the Bordeaux Institute of Journalism and the Efet photography school, Guillaume Garvanèse is a journalist and photographer, specialized in health and social issues. He has worked for the French group Moniteur.