You are here

Deep into Japanese Suburbs

Japan has a population of 120 million, twice that of France. Tokyo is home to 38 million inhabitants, which is five to six times more than the Greater Paris region. In what way is Japan’s urbanisation exemplary?

Cécile Asanuma-Brice:1 Japan’s urbanisation is not exemplary — it illustrates how a city is ‘produced’ according to capitalist logic. Tokyo has long been much larger than Paris geographically and far less polluted. For me though, it is the place where the ravages of the ‘global’ city are the most striking, in particular the disconnection from the natural world, which nonetheless is a pillar of Japanese culture. At first, I wanted to investigate public investment in housing and urban planning. Why does a country decide at a given moment to invest in its citizens’ dwellings — a highly personal asset after all? And yet such investments have been made by all of the countries that opted for capitalism, and its financial system, when they initiated the process of industrialisation. To put it simply, Europe’s upper classes wanted to prevent a new revolution by giving the working and middle classes access to a certain standard of living. In addition, the trauma of the major plague epidemics (in the Middle Ages, in the 19th century… — the last cases in France were reported in the late 18th century) still cast a shadow over Europe, and poverty was rampant, making it necessary to maintain a minimum of hygiene in cities. That was the primary motivation behind public housing. In Japan, the triggering events were the Great Kanto earthquake of 1923 and the Second World War. Given the extent of the damage — 465,000 homes destroyed in 1923 and 2,700,000 in World War II — an urgent solution was needed for rehousing the population.

What turns a city into a suburb?

C.A.B.: This is what my book2 is all about! My first question was whether I could use the word ‘suburb’ when talking about Japan. The French word banlieue is laden with connotations: the area, or lieu, where those who lived outside of town were subject to a tax called ban. None of that existed in Japan. The Japanese word for suburb is kôgai. It’s an in-between term to describe the city encroaching on the countryside and the countryside becoming urban. It also encompasses the meishos, or places where people went to enjoy visual or auditory landscapes like plum trees in bloom or the song of cicadas. It was a countryside near the city.

But were the processes at work the same in Tokyo and Paris?

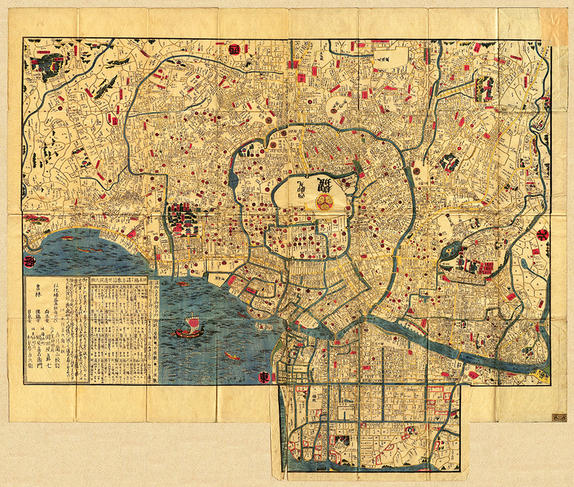

C.A.B.: They weren’t as different as one might think. First of all because Tokyo, like Paris, had walls — there was an ‘inside’ and an ‘outside’. By definition, there was nothing natural about the city. As soon as an emperor or a king settled in a given location, the upper class came to live nearby. All sources of pollution were subsequently moved aside, shielded from the wind, with the poor living in the outlying flood-risk zones and the middle class artisans stuck between the two. Paris and Tokyo were no exception. The two cities then developed in successive waves of urban planning that focused on providing housing for the workers and employees who were to drive the new economic system that many countries had chosen.

What effect did this have?

C.A.B.: Unlike Tokyo, Paris had ‘La Zone’, a strip of land surrounding the capital, where construction was banned. Although nothing could be built there, it ended up being occupied by allotments. When provincials came to Paris en masse in the hope of finding work, Parisians moved out, because the city was becoming overcrowded. The evolution was as follows: the people from Paris went out to the suburbs, built little sheds and planted vegetable gardens, which they visited on Sundays with the family. As this lifestyle developed, they brought in water, added an extra room, and eventually decided to live there full-time. That’s how the early suburban houses came into being, a trend that very quickly posed its own health problems, since at first there was no running water, electricity, etc. It was the Wild West: people cut down the trees and settled in. Soon, real-estate developers saw a godsend. They began buying and reselling plots of land that were not at all adapted for residential use. This triggered a planning impetus, which led to the development of public rail services. In Tokyo, the process was reversed. The pioneers of Japanese capitalism bought rail lines and extended them to the suburbs. They first installed parks, and parcelled out the land around their train stations to build houses for the middle class.

There is a 50-year gap between the industrialisation of Europe and Japan…

C.A.B.: Japan adopted the capitalist industrial system rather suddenly after the Meiji Restoration3 and the opening of the country to international trade in 1868. For that reason, looking at the transformation of the Japanese city is a quick way to gain insight into what happened in other industrialised countries over a longer period, given that development models were mostly imported from the West. At first they came from Europe, with the experiments initiated by manufacturers, like the garden cities of Ebenezer Howard4 or the Familistère in Guise, northern France,5 and Japanese envoys going to study working class housing in Europe in the early 20th century.

In Japan, the most successful achievement was no doubt Manjû Kôba, developed on this model by Ôhara Magosaburô in Kurashiki in the 1930s . It’s a perfect illustration of the ‘city in the countryside’, planned around an industry but conscious of its workers’ quality of life, seeking to provide education for them and their families, a balanced existence and general well-being. At that time, workers in Japan were housed in dormitories, which caused hygiene problems and made family life impossible. When he took over his father’s company, Magosaburô decided to change everything: he built houses to enable workers to have a family and live off the company, instead of the company living off them. This inversion is fundamental. Later models came from the United States — the New York World’s Fair of 1939 was a decisive influence. After World War II, when Japan was occupied by the US, it adopted the American model and all of the ideas of new capitalism. At the time, this was seen as highly beneficial for everyone.

What fundamental changes have resulted from Japan’s entering the industrial and then capitalist eras?

C.A.B.: Looking back at a century of history, space management radically changed before and after the entry into the capitalist era. Understanding urbanisation in Japan also means identifying the biases of ‘global’ urban planning methods and the way they destroy our relations with nature through the systematic concretisation of spaces, the selection of plant species, etc. As I explain in my book, the suburb has been totally reshaped by a desire for rationalisation arising from capitalist thought, with no connection to the place or to history. The urban fabric thus created, to meet the needs of the new economic system, has resulted in new cities that degenerate into dormitory towns. Ultimately, it has turned the city into an object — an industrialised object like any other, a desolate place with concrete surfaces everywhere, which no doubt contributes to global warming. The functionalisation of space, leading to its compartmentalisation, has also affected interpersonal relations. The suburbs offered space for the consumer society at affordable prices, which was consistent with the logic of the system. That’s where constructions were first erected artificially, rather like playing with Lego.

Could it be said that the Fukushima disaster, like the 1923 earthquake, is a milestone in the urbanisation processes?

C.A.B.: The earthquake of 1923 occurred in the Kanto region, a dense urban area, at noon, when people were preparing lunch. At the time, they used wood fires, and since the houses were made of wood, everything burned. The fires spread, and Tokyo and Yokohama were wiped off the map. I mention Fukushima in my book because on the Tohoku Coast, part of the seashore was built using the model of consumer society suburbs — with the idea, also adopted from the West, of considering the seaside a recreational site, a concept that is not shared by all cultures. In fact, if tidal waves were given a Japanese name, ‘tsunami’, it is because they regularly occur in Japan. People are familiar with them and, in principle, know how to use the space available to avoid damage.

However, tidal waves are not all that frequent, and the new urbanisation has erased previous generations’ warnings against occupying certain zones. The kind of urban dwellings that were built in the suburbs extended over the coastlines, pursuing Western criteria of a sea view, easy access to the beach, etc. As a result, suburban development has spread to places that should have been left free.

What was the response in terms of rehousing?

C.A.B.: Most of the people affected by the tsunami or the nuclear disaster were farmers who could have been relocated to vacant accommodation in the surrounding mountains. But rather than rehabilitating those dwellings — which would have made everyone happy because it would also have revived the villages —the preferred solution was to build temporary housing on-site, with no insulation, on parking lots. For those people used to living on large farms, these confined spaces meant that they could no longer be with their families, forcing them into a solitude that sometimes proved fatal.

What do you think could be the solution to the spiral you describe?

C.A.B.: I think that we have been addressing the wrong problem for years. A sprawling city is not ecologically more destructive than a high-density one if it is properly balanced and reincorporates local shops and services. It’s time to break away from functionalism and its associated rationality, which has proven ill-adapted to life’s needs. A living system needs to flourish in all its complexity. As a result, the answer to today’s urban problems is not to be found in the much-touted concept of ‘shrinking cities’. The economic logic behind the shrunken urban space and its wave of ever-denser collective housing has led, on the contrary, to the production of spaces that are extremely energy-hungry, ecologically unviable, detrimental to community relations, and a source of contradictions. The latter are mainly of two types: first, vacant housing proliferates in all metropolises, along with the number of homeless people; and second, the cities that do the most business have the worst housing (as in Hong Kong) because the financial pressure is so high. It is therefore essential to revert to an urban model in which nature and social ties play a central role.

To read (French):

Un Siècle de Banlieue Japonaise (A Century of Japanese Suburbs), C. Asanuma-Brice, Métis Presses, 2019, 256 p.

- 1. Cécile Asanuma-Brice is a visiting researcher at the CLERSÉ (Centre Lillois d’Études et de Recherches Sociologiques et Économiques - CNRS / Université de Lille) and at the Maison Franco-Japonaise research centre in Tokyo (CNRS).

- 2. Un Siècle de Banlieue Japonaise (A Century of Japanese Suburbs), C. Asanuma-Brice, Métis Presses, 2019, 256 p.

- 3. Name assumed by Emperor Mutsuhito when he ascended to the throne.

- 4. Ebenezer Howard (1850-1928), the British urban planner who founded the garden city movement.

- 5. The Familistère de Guise, a cooperative communal establishment developed between 1859 and 1884 by Jean-Baptiste André Godin (1817-1888) in Guise (northeastern France), based on the phalanstery of Charles Fourier (1772-1837).