You are here

Bringing the Chartres Manuscripts Back to Life

This is a labor of love that only genuine devotees of ancient books would have the patience to undertake: for more than ten years now, researchers at the IRHT,1 working in collaboration with the National Library of France (BNF), have been meticulously attempting to restore the medieval manuscripts of Chartres. Or at any rate, what remains of them, after the Americans accidentally bombed the center of Chartres on May 26, 1944, burning down the public library where the precious documents were kept.

"Of the 518 listed manuscripts, 45% were totally destroyed," says Dominique Poirel, a specialist in medieval Latin texts at the IRHT. "Those that survived have been reduced to tens of thousands of scattered fragments, since most of the bindings were burnt." Many are illegible due to the combined effect of the fire and of the water used by firefighters to put out the blaze. Some are completely blackened, or so worn that they have become transparent, while others are washed out and their ink faded.

A priceless medieval collection

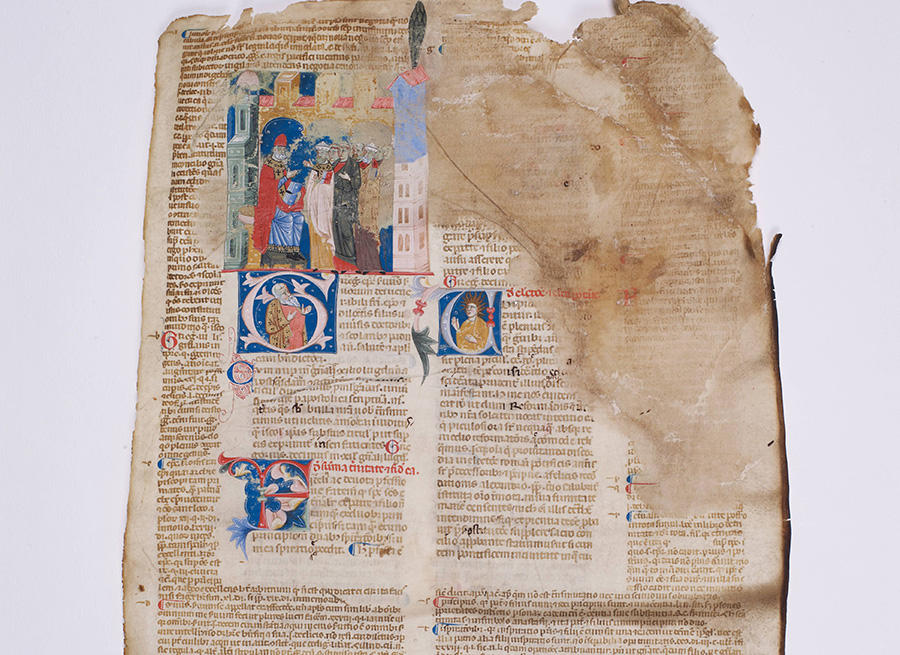

It was a huge loss for medievalists and historians, since the manuscripts formed a remarkable ensemble in more than one respect. "The collection comes from confiscations during the French Revolution, especially from two major sources: the chapter of Chartres cathedral and the Benedictine abbey of Saint-Père-en-Vallée," explains Claudia Rabel, a specialist in medieval iconography at the IRHT, who jointly with her colleague, heads the program for the virtual recovery of the ruined Chartres manuscripts. "In particular, it includes an exceptional number of Carolingian parchments from the eighth to tenth centuries."

The collection also bears witness to the fact that, in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, Chartres, with its famous School, was one of the leading centers of scholarship in Western Christianity. "The distinctive feature of the School of Chartres, represented by clerics such as Bernard and Thierry de Chartres, Gilbert de Poitiers and Guillaume de Conches, was to reconcile theology with the secular knowledge inherited from antiquity," says Poirel. "In particular, the School showed a genuine interest in the sciences and in medicine, and it attempted to reconcile data from the Bible with Greek science and philosophy." All this makes the manuscripts a priceless treasure, and one that it was imperative to recover.

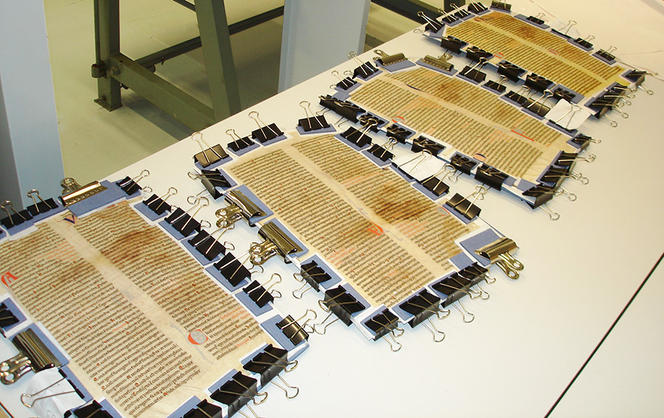

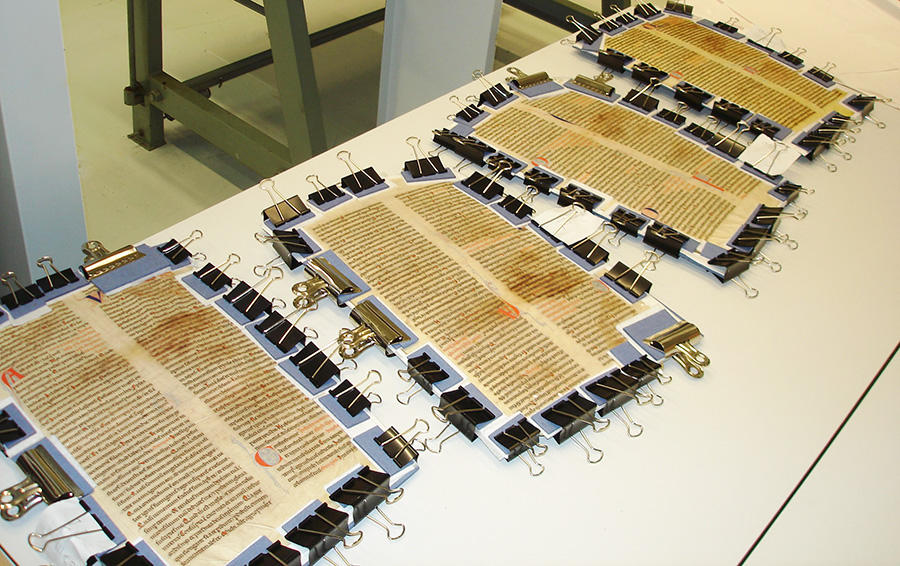

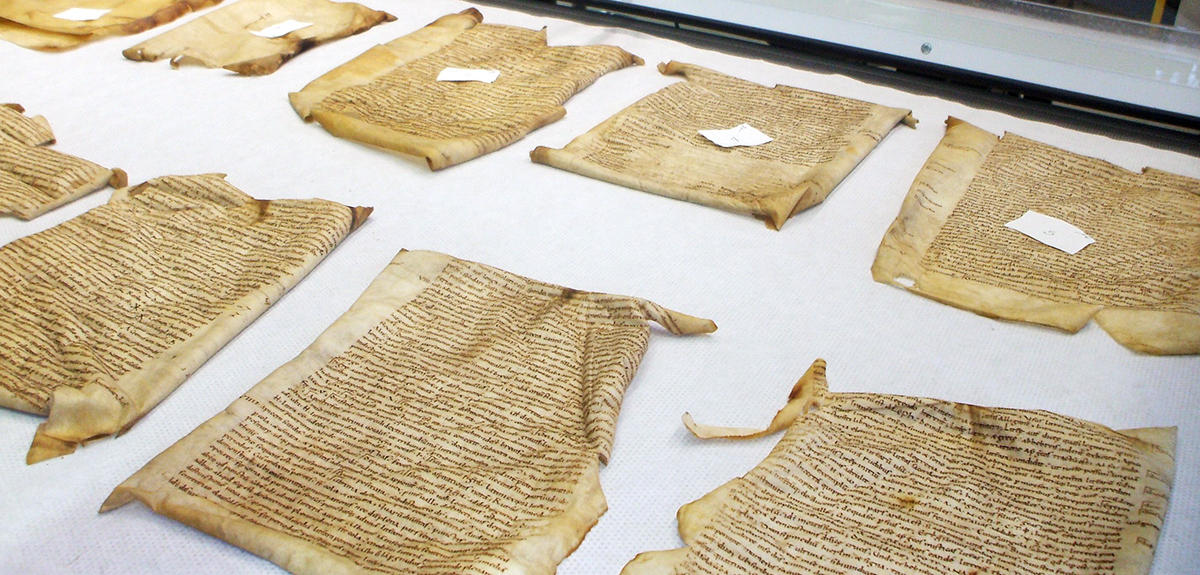

Softening up parchments

The recovery of the Chartres collection took place in several stages, beginning with a long, meticulous restoration phase, carried out from 2009 to 2012 at the National Library of France's workshops in Bussy-Saint-Georges (near Paris). "Most of the manuscripts are made up of sheets of parchment, in other words of skin, that were badly damaged by the heat of the fire, which warped and hardened them," Poirel explains. The National Library's humidification chamber was used to soften them and restore their flexibility, before moving on to the next stage, digitization. The thousands of photos of the fragments, whether restored or not, were then made available online on the Virtual Library of Medieval Manuscripts (BVMM), an open-access website.

Another challenging project that directly involves the IRHT's researchers is to identify which documents the loose sheets belong to and put them back in order, even though most of the page numbers were destroyed by the fire. "Fortunately for us, a catalog dating from the late nineteenth century lists the Chartres manuscripts. Some of them were even microfilmed before the Second World War," says Rabel. "To date, 33 of the 161 digitized medieval texts have been put in order, while 14 of them have already undergone detailed scientific study.”

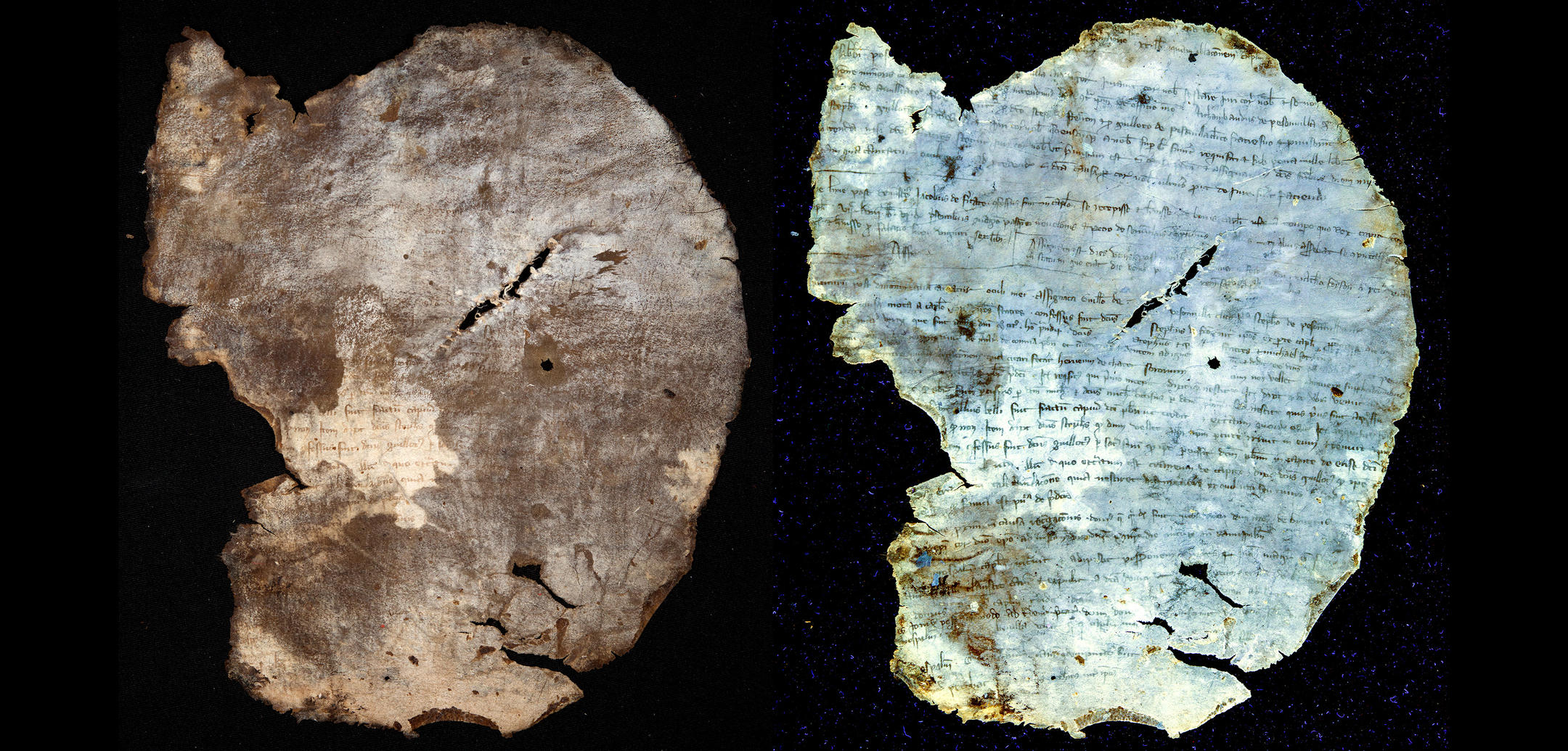

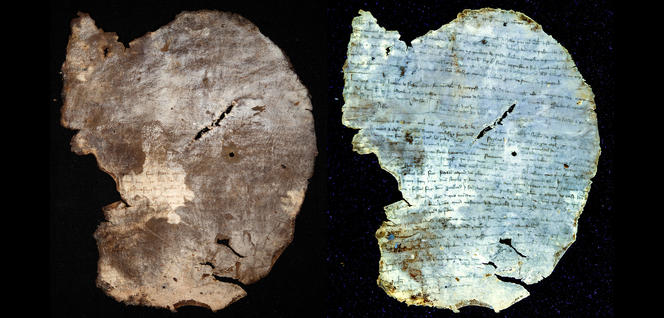

Reading with ultraviolet rays

A major hurdle however remained to be overcome: that of deciphering the pages made illegible by fire and water. Although the human eye is incapable of doing this, an innovative image processing technique developed by the Center for Research on Preservation (CRC)2 has solved the problem. The principle is based on illuminating the manuscript and taking photographs across the light spectrum, at all wavelengths from ultraviolet to infrared, to determine which ones are the most suitable for reading black ink on a blackened parchment, or for deciphering an almost translucent document. "So far, the best results for the Chartres manuscripts have been obtained with ultraviolet light," Rabel explains. Specialists and non-specialists alike will soon be able to enjoy some of these spectacular 'before and after' images on the website of the Virtual Library of Medieval Manuscripts.

The digitized Chartres manuscripts can be consulted on the website of the program 'À la recherche des manuscrits de Chartres' and on that of the Virtual Library of Medieval Manuscripts.