You are here

The end of the death penalty marked a sharp turn in French history

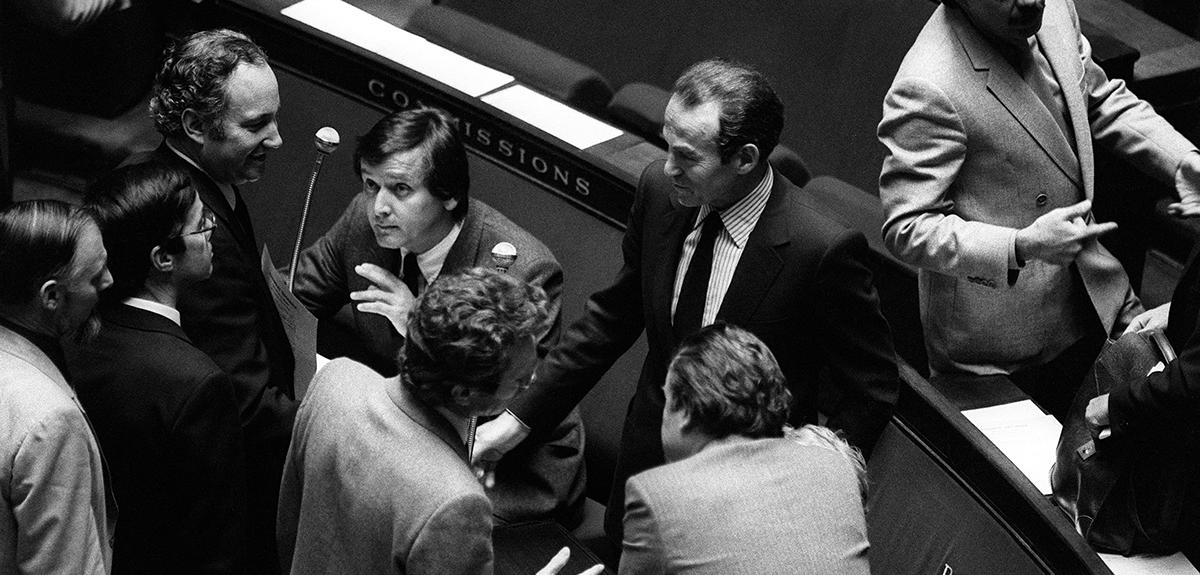

Article 1. The death penalty is abolished. Announced in the Journal Officiel (French official journal) on 10 October, 1981, law n°81-908 condemned capital punishment to oblivion, making France the 35th country to abolish it. After severing several thousand necks over two centuries, the guillotine was decommissioned, largely due to the efforts of Robert Badinter, Minister of Justice of the socialist government under Prime Minister Pierre Mauroy (1981-1986). In a now-famous speech before the National Assembly on 17 September, 1981, this lawyer and ardent defender “of a certain conception of man and justice” proclaimed: “Tomorrow, thanks to you, French justice will no longer be a justice that kills. Tomorrow, thanks to you, there will no longer be, to our common shame, stealthy executions, at dawn, under the black canopy, in the prisons of France.”

Adopted counter to popular sentiment (at a time when 63% of French citizens were in favour of the guillotine) but part of the agenda of the newly-elected left-wing majority, the abolition of capital punishment stood as the culmination of a struggle that had inflamed the political arena and public opinion at several points in history (1791, 1848, 1908). Is there any turning back? Since 1981, dozens of requests to reinstate the death penalty have been filed in the National Assembly, and according to a recent survey, 55% of the country’s population would approve.1 “The abolition was enshrined in the Constitution in 2007, and France has ratified Protocols 6 and 13 of the European Convention on Human Rights, as well as the Second Optional Protocol to the United Nations International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights,” notes Serge Dauchy, director of the CHJ2 in Lille (northern France). “In order to restore capital punishment, we would have to revise the Constitution, withdraw from the European Union and renege on some of our international commitments.” Not to mention the fact that all of the studies conducted by criminologists have concluded that there is no link between the death penalty and the evolution of criminality.

Public authority and legitimate violence

Still, rewinding the very long film of the history of the ultimate punishment shows that most societies, until recent times, included it in their criminal legislation. For thousands of years, with virtually no exceptions, all public authorities that claimed a monopoly on legitimate violence, and thus outlawed any recourse to private vengeance, reserved the right to impose death as a sanction for the crimes that they deemed most detrimental to the social, moral, religious or political order. And all of these powers had to address the same questions. How can capital punishment be used to protect society against its most dangerous enemies, uphold the state’s authority and deter future delinquency? Which is the best method of execution? Should it be public in order to make an impression? Should women and children be put to death in the same way as men? And so on.

In the late Middle Ages (12th-15th century), with the re-emergence of Roman criminal law, the rise of monarchical centralisation and royal justice gradually replacing feudal justice, “punishing those who resisted the established order seemed to be a growing necessity,” explains Tanguy Le Marc’hadour of the CHJ. The idea took root that criminals should redeem their crimes by personal sacrifice, and that the greater the offence, the more its perpetrator should suffer. Punishable by death were homicide, arson, the burning of harvests, theft, rape, kidnapping, counterfeiting of currency and religious relapse (for a Christian, the fact of re-espousing a previously renounced heresy).

As for the methods, hanging – a simple process – was the most common, far ahead of quartering, drowning, beheading with a sword, burning at the stake, scalding or burying alive… But contrary to common belief, “the death penalty was not excessively applied in the Middle Ages”, Le Marc’hadour specifies. “Legal sources show that between the 13th and 16th centuries, judges sought to gather as much irrefutable evidence as possible that the defendants had indeed committed the crimes they had been accused of. And the most common punishment, for those found guilty, was banishment – from their city, province or kingdom, for a long period or for life.” This solution allowed society to rid itself of undesirable individuals without having to physically eliminate them.

Closed trials, public executions

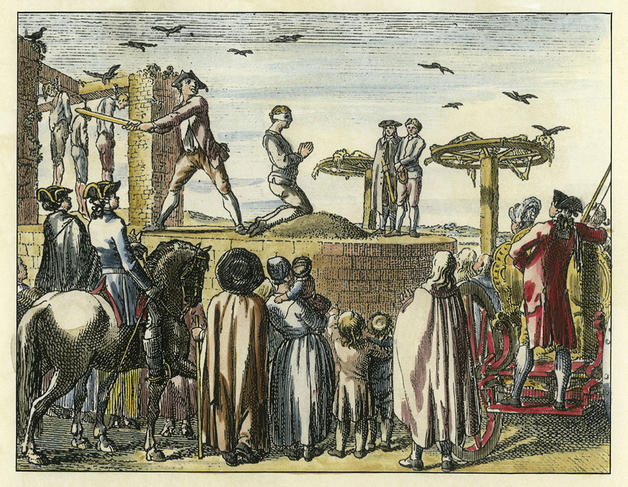

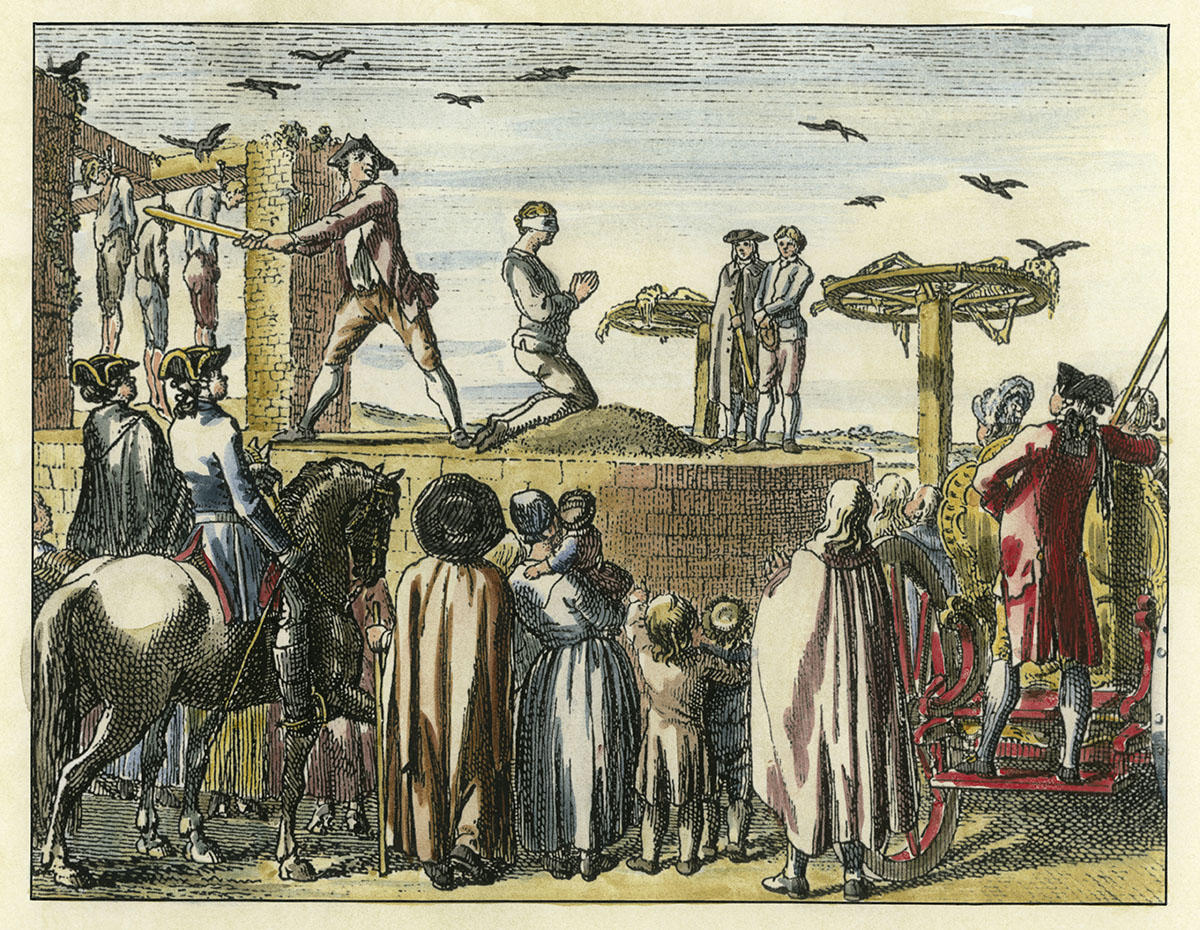

In the 16th century, interreligious strife plunged France into chaos, and in the early 17th century the war on heresy and witchcraft led to a sharp rise in the number of executions. Imposed by King Francis I in order to “instil fear, terror and an example,” the torture of the wheel, a form of public execution in which the prisoner’s limbs and ribs were broken with an iron bar, was increasingly used to punish perpetrators of the most serious crimes.

From the wheel to the galley

“Under the Ancien Régime, all punishments were for public viewing,” Le Marc’hadour recounts. “No one could imagine a crime being sanctioned ‘out of sight’. Trials were held behind closed doors, but the sentence was staged out in the open, to demonstrate the state’s power over the bodies of its prisoners and make a cautionary example of them. By the same token, it was important for convicts under a death sentence to suffer physically, thus making their execution the expression of public retribution, even though the verdicts very often included a secret clause (called the retentum) specifying that the executioner was to kill the convict before or during the process. As a result, the torture of the wheel was nearly always inflicted on a dead body.” The main point was that the onlookers did not know.

Did the French courts of the 18th century make extensive use of the death sentence? Apparently not. In the 1780s, the Parliament of Paris,3 whose jurisdiction extended north to Boulogne sur Mer and south to Lyon, handed down a total of some 50 death sentences per year, and the Parliament of Flanders, which ruled over a territory roughly equivalent to the current Nord region, fewer than three. “The monarchy encouraged the courts to send criminals to the galleys rather than the wheel,” Le Marc’hadour says. “In the entire kingdom, between 400 and 500 prisoners were sentenced to galley service each year. In this way, the justice system offered the navy a population of convicts who, if not serving in actual combat, provided much-needed additional manpower for the country’s main naval shipyards. This change of paradigm came in response to an economic necessity.”

The Enlightenment and the legality of crimes

Of equal importance is the Enlightenment, which questioned the very principle of capital punishment, and whose rationalist and humanist ideas spread across Europe. In a book entitled On Crimes and Punishments, published anonymously in Livorno, Italy, in 1764, a 26-year-old Italian marquis named Cesare Beccaria became the first author to assert that the death penalty was “neither useful nor necessary”, had never “made mankind better”, and prevented rectification of miscarriages of justice. A veritable reference manual for enlightened sovereigns, the pamphlet proposed “perpetual slavery” (life imprisonment) as a substitute. Won over, Grand Duke Peter Leopold abolished capital punishment in the central western Italian region of Tuscany in 1786. A world first!

On the French side of the Alps, Beccaria’s ideas appealed to Diderot, D’Alembert, Voltaire, and many of the revolutionaries. The latter, in the criminal code that they adopted in September 1791, the first of its kind in France, embraced “the principle of the legality of crimes”, according to which every penal sentence must be based on a specific law, and also abolished all forms of torture with the exception of the amputation of the right hand for parricide. “However, this met with resistance, especially from public opinion, that was too strong for the abolitionists to succeed,” recounts Bruno Dubois, also of the CHJ. Capital punishment was maintained by the early revolutionary government, the Constituent Assembly, albeit for a reduced number of crimes (32, as opposed to some 100 at the end of the Ancien Régime), and decapitation by guillotine was adopted as a method of execution, to spare those sentenced to death from having to endure suffering as horrendous as it was unnecessary.

A later government, the Convention, made the leap. On the 4th of Brumaire, Year IV (the revolutionary calendar designation for 25 October, 1795), weary of the ravages of the “Patriotic Razor” under the Reign of Terror, the parliament declared that “starting from the day of the general proclamation of peace, the death penalty would be abolished in the French Republic”. However, by the time peace was restored in 1802, Napoleon had come to power. As both the bearer and destroyer of the Revolution, the emperor was not in favour of abolition. The highly repressive, so-called “iron” criminal code introduced in 1810 listed 36 crimes punishable by death. And the subsequent Restoration of the monarchy was hardly less severe: nearly 3,800 death sentences were handed down between 1816 and 1830 – almost one per working day.

Abolition as a public issue

Later, under the impetus of François Guizot, one of the leading ministers of the July Monarchy, “the law of April 1832 eliminated capital punishment for nine types of offences, including the burning of buildings, ships, boats, stores, etc.”, Dubois recounts. “Inspired by the doctrine that one should punish ‘neither more than is fair, nor more than is necessary’, the same law limited the death penalty to crimes against persons (homicides) and introduced the concept of mitigating circumstances, which considerably reduced the number of death sentences and thus of executions. Similarly, in 1848 the provisional government of the Second Republic, led by the poet and politician Lamartine, abolished capital punishment for political crimes.” This was one more step towards the total abolition that the famous French writer Victor Hugo (1802-1885) relentlessly advocated, arguing that “wherever the ultimate sentence is rare, civilisation reigns”.

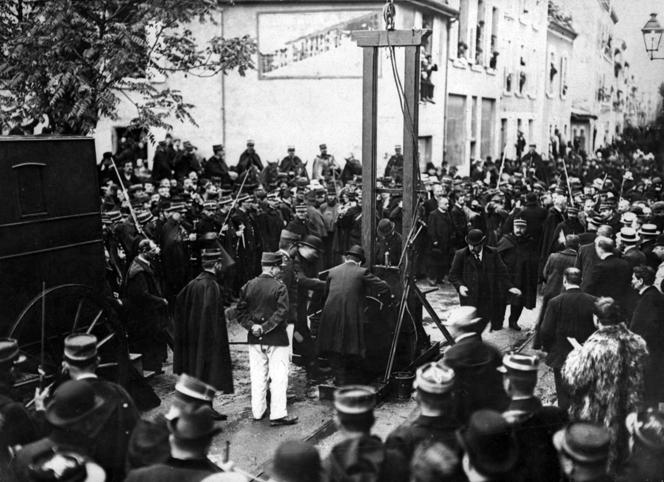

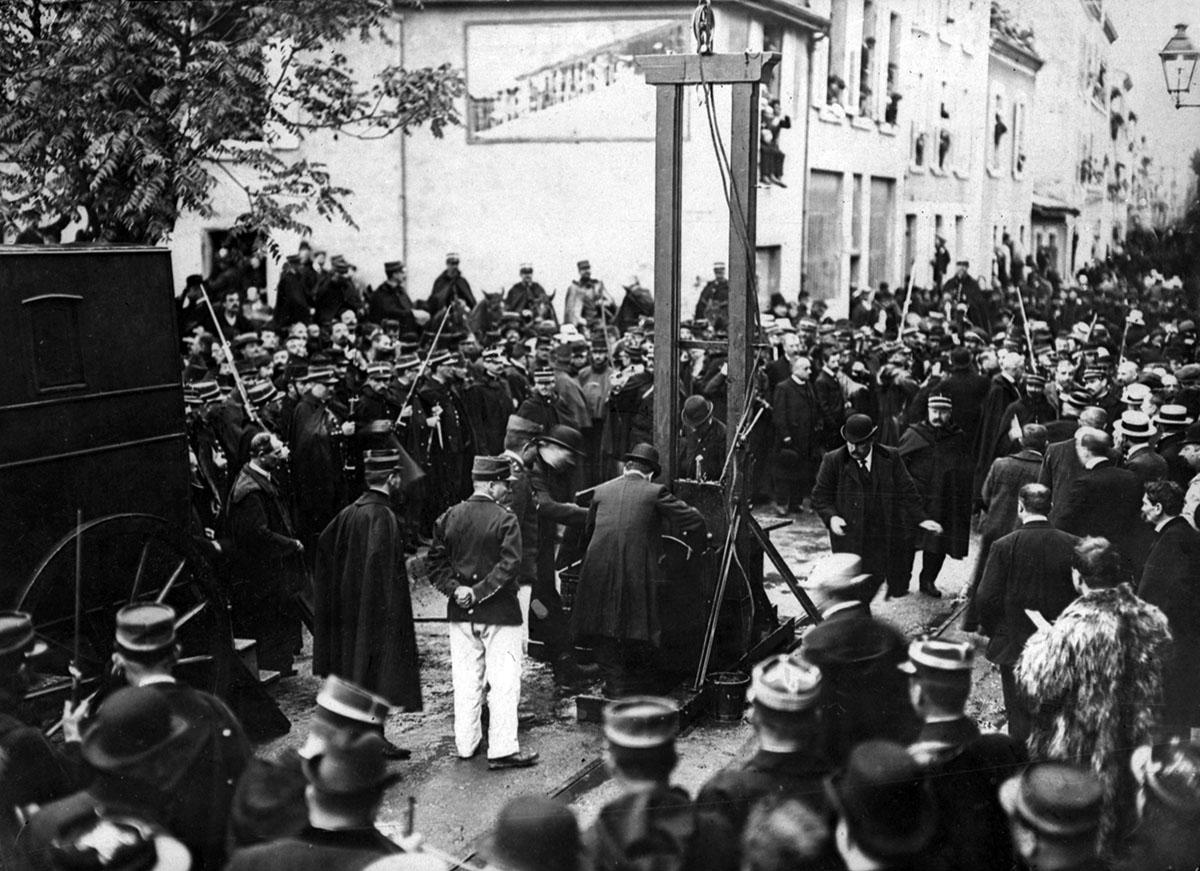

“In the 19th century the suppression of capital punishment became a subject of public debate, a social issue,” Dubois says. The abolitionists’ legal-philosophical arguments included the atrocity of the process, its ineffectiveness as a deterrent, the bad example set by a government that kills its prisoners, thus encouraging bloodshed, and the impossible rectification of miscarriages of justice. Meanwhile, the anti-abolitionists stressed the exemplary nature of the punishment, the rising crime rates, the existence of irredeemable criminals and the population’s demands for law and order. The presidents of the Third Republic (1870-1940) made broad use of their power of pardons and commutations, with the exception of the first chief executive, Adolphe Thiers. From 1872 onwards, in an effort to downplay the pageantry and avoid inciting violent impulses, the guillotine was no longer erected high on a scaffold but on the ground, and executions were held earlier and earlier in the morning, in secluded locations.

A surge in support of capital punishment

The Radicals’ legislative victory in 1906 gave the abolitionist cause a tremendous boost. After Portugal (1867) and Italy (1890) – “non-democratic countries where public opinion carried less weight than in France”, according to Le Marc’hadour – France at last seemed ready for abolition.

However, in the middle of the parliamentary debates, the murder in Paris of 11-year-old Marthe Erbelding by Albert Soleilland sparked outrage, unleashing a torrent of pro-capital punishment articles in the tabloid press, especially when President Armand Fallières, a fervent abolitionist, commuted the death sentence. On 8 December, 1908, the repeal backed by the Minister of Justice Aristide Briand, socialist parliament member Jean Jaurès and Council President the equivalent of today’s prime minister Georges Clémenceau was rejected by a vote of 330 to 201.

There were no further parliamentary votes on abolition until 1981. The left’s time in opposition, the First World War, the crimes of the Occupation, the purge after the Liberation and the upheavals of decolonisation all pushed the debate further from the spotlight. Still, over the years, the number of death sentences continued to drop, slowly but steadily, and public executions were increasingly considered barbaric. France’s last public decapitation, of the serial killer Eugène Weidmann, took place in Versailles (near Paris) on 17 June, 1939. From then on, the guillotine was kept out of sight behind prison walls. But abolition was still a long way away.

Victory of the abolitionists

Championed by human rights associations, international organisations and the Council of Europe, the abolitionist cause has now prevailed in every European country except Belarus. On a global scale, more than two-thirds of the world’s countries have abolished the death penalty in practice (the punishment is still legal but no longer applied) or reserve it for war crimes and military courts. But in terms of worldwide population, two out of three people still live under its threat.

According to the grim statistics of the NGO Amnesty International, 657 executions were carried out in 2019 in 20 countries, with China, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Iraq and Egypt topping the list. “Nonetheless, we note a downward trend,” Serge Dauchy reports. “Capital punishment is increasingly marginalised.” This is the case for example in the United States: although Donald Trump presided over more federal executions than any of his modern-day predecessors (13 in all), his successor Joe Biden has promised to “eliminate the death penalty at the federal level, and incentivise states to follow the federal government’s example”. On 24 March of this year, Virginia thus became the first southern state to abolish the ultimate punishment.

- 1. IPSOS / Sopra Steria survey for Le Monde, conducted online on 1-3 September, 2020 with 1,030 respondents aged 18 and over.

- 2. Centre d’Histoire Judiciaire (CNRS / Université de Lille).

- 3. During the Ancien Régime, the Parliaments administered justice in the name of the king, most often on appeal but also for cases of first instance.

Explore more

Author

Philippe Testard-Vaillant is a journalist. He lives and works in south-eastern France. He has also authored and co-authored several books, including Le Guide du Paris savant (Paris: Belin) and Mon corps, la première merveille du monde (Paris: JC Lattès).