You are here

Innovation and emotion form part of heritage preservation

3D printing, new imaging methods, multidimensional digitisation of objects and monuments… Researchers, professionals and political figures gathered at the Louvre museum and the Bibliothèque Nationale de France on 15 and 16 March to discuss the latest developments in the heritage sciences, including analysis and preservation. Entitled “A Heritage for the Future, a Science for Heritage”, the colloquium was hosted by the FSP heritage sciences foundation under the auspices of the French presidency of the Council of the European Union.1

Digital technology, now an indispensable ally

According to Livio de Luca, director of the Models and Simulations for Architecture and Heritage (MAP)2 research unit, the event took place at a turning point, marked by the confluence of two major evolutions in the heritage sciences. First, scientific research is no longer an individual pursuit in which isolated experts examine an object or a collection with no outside assistance. “Today the mechanism of knowledge production is collaborative and even participative,” he says.

Secondly, “For the first time, digital techniques are truly considered a full-fledged, separate area of research in the heritage sciences,” the scientist reports. His statement is borne out by the progress made in the digitisation of the architectural heritage. “We started with texts, then images, and now we’ve moved on to digitising three-dimensional forms,” he explains.

“Today we can go beyond visual appearance,” De Luca adds. “Digitisation has become a multidimensional ecosystem making it possible to associate a heritage object with all of the pertinent scientific knowledge and data available.” Chemical composition, ultraviolet imaging and microtopography, as well as archaeological, iconographic, historical and literary information: the thousand and one facets of an artefact are now integrated into its digital model.

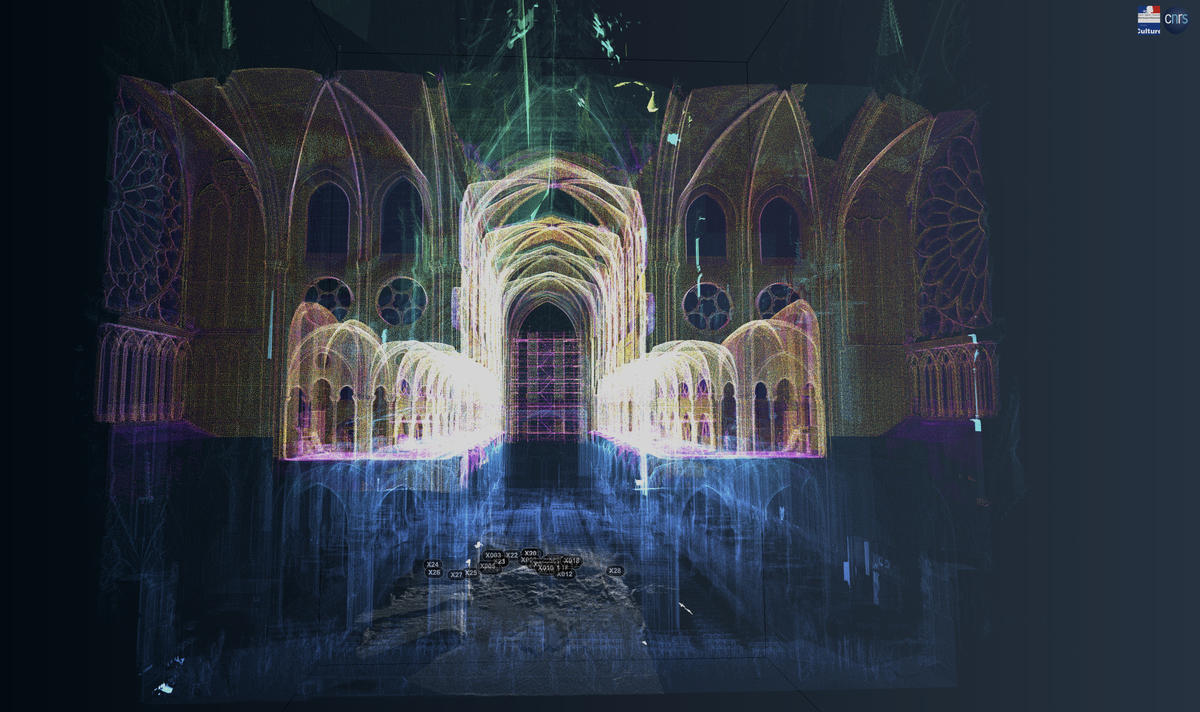

A high-profile example of this evolution, discussed in depth at the symposium, is the Notre Dame de Paris renovation project, for which digitisation is revealing its full potential. Coordinated by De Luca, the “digital data task force” is creating a digital ecosystem incorporating everything that is known about Notre Dame, including the findings of the 170 researchers of all disciplines who are participating in the project. “Along with the reconstruction, we are building a cathedral of data and knowledge,” De Luca says.

This digital “hypercathedral” makes it possible to “expand the realm of possibilities” by cross-referencing perspectives that would not otherwise intersect. At the same time, it is a precious tool for the rehabilitation of the “bricks and mortar” Notre Dame. For example, the accurate reconstruction of the vaults and roof structure could not proceed without the mass of data gathered before the fire.

Emotion and civic indignation

Digitisation also plays an important role in the public’s relationship to heritage, which is why various innovative mediation solutions were presented at the forum. A roundtable was held on virtual museum tours, digital tablets and QR codes for on-site visits, and using the social networks to enrich the heritage experience. Other forms of mediation between the public and cultural heritage were also discussed. Contemporary art, for example, seeks to offer fresh viewpoints on familiar objects. However, its success is far from guaranteed – the ethnologist Sylvie Sagnes, a researcher at the Heritage: Culture/s, Patrimony/-ies, Creation/s laboratory3 presented a case study that sheds light on the problematic interaction between heritage and artistic creation.

In 2018, to celebrate the 20th anniversary of the listing of the mediaeval citadel of Carcassonne (southwestern France) as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, the CMN French national monument centre commissioned a large-scale work from the Swiss artist Felice Varini, who painted concentric yellow circles on the town’s ramparts. The work met with outrage among the local residents, who launched petitions and even carried out acts of sabotage.

Sagnes wanted to understand their reaction. “The inhabitants of Carcassonne are very fond of the mediaeval enclave, but feel dispossessed from it because of the mass tourism it attracts,” the researcher explained. “In their eyes, Varini’s work came across as graffiti, defacing the only part of the city that was left to them: the view of the walls.” In other words, as soon as a cherished heritage symbol is perverted, a community, city or country suddenly rises up in reaction. This is what anthropologists call “a patrimonial emotion”: feelings of outrage and indignation that can trigger a popular uprising to defend a heritage.

“These reactions are a way of claiming the right to one’s historical legacy, and even an affirmation of a patrimonial democracy,” Sagnes asserts. This type of emotional response emerged when Notre Dame went up in flames. The researcher is a member of the Notre Dame scientific project, working with a group that is analysing the anguish that was so widely felt during the fire. “Through an online questionnaire, we’re trying to codify the memories of people who feel an attachment to the cathedral, in order to understand the impulses behind the emotional reactions to 15 April, 2019.”

Ukraine on everyone’s mind

In the days before the symposium, the situation in Ukraine was on everyone’s mind – the humanitarian crisis first of all, but also the threat to the vast cultural heritage of a country under bombardment. Already, UNESCO drew attention to United Nations Security Council Resolution 2347, which condemns the destruction of religious sites and objects, as well as the looting and trafficking of cultural property. “There is an element of tragedy in heritage,” Sagnes comments. “During periods of crisis and violence we become keenly aware of its fragility, and that’s when we realise that it’s the very foundation of identity.”

With the disaster unfolding in Ukraine, the digitisation of cultural property takes on new significance. “In countries at war, like Syria for example, expeditious digitisation campaigns have been carried out using drones and other 3D acquisition methods. The goal is to collect and store as much data as possible in order to preserve the memory of the object,” De Luca reports. “In this respect, some Ukrainian and Czech colleagues have performed remarkable research work for the purpose of creating 3D reconstructions of monuments and buildings based on photos taken by tourists.” In this unexpected way, the Paris symposium was tinged with a sense of urgency, passion and mobilisation.

- 1. The event was organised by the FSP (Fondation des Sciences du Patrimoine) with the backing of the European Commission and in partnership with the French Ministry of Culture, the CNRS and the universities of Paris-Saclay and Cergy Paris.

- 2. CNRS / French Ministry of Culture.

- 3. CNRS / CY Cergy Paris Université / French Ministry of Culture.