You are here

The Middle Ages brought Epicurus out of the underworld

The image handed down to us of the Greek philosopher Epicurus (341-270 BC), is that of a man with a zest for life who lives in endless pursuit of all earthly pleasures. Is this an accurate depiction of the ‘real’ Epicurus?

Aurélien Robert:1 No – it is a caricature whose history I am trying to retrace. The ethical principles upheld by Epicurus actually leaned towards a rather radical form of asceticism. Pleasure, in the eyes of this ancient philosopher, is indeed a reliable guide for finding one’s way in life, but that doesn’t mean pursuing all pleasures blindly. The wise must learn to content themselves with the fulfillment of their vital needs (eating, drinking, sleeping, etc.). Consequently, Epicurean morality is by no means an injunction to engage in lust and debauchery. It defines happiness as a state made possible by the absence of torments for the soul and ailments for the body. Moreover, Epicurus did not deny the existence of the gods. He simply asked that they be imagined as untroubled, entirely peaceful and indifferent to human affairs, and that mankind take them as models. To achieve happiness, he said, one should live ‘like a god among men’ – in other words leading a life free of anxieties related to fear and death, ruled instead by a quest for moderate, lasting pleasures.

When did he become seen as an impious, immoral, compulsive pleasure-seeker?

A.R.: The third-century Greek author Diogenes Laërtius reported that Epicurus was already vilified in his own lifetime. Yet such disparagement escalated in the second century. At the time, Epicureans were still active in the easternmost regions of the Roman Empire, where the first Christian communities had settled. In Asia Minor (today’s Turkey), Syria, Palestine and Egypt, Epicurean schools were in territorial and intellectual competition with Christian groups. In response to the persecution they were suffering, the early Christians submitted written apologies of their faith to the highest Roman dignitaries, including the emperor himself, arguing that their beliefs and practices were no more incompatible with Roman mores than those of their pagan adversaries, the Epicureans in particular. To serve their own cause, they gradually fabricated the image of Epicureans as atheists, hedonists and, for the first time, heretics. Ultimately, Christianity won the upper hand with the conversion of Emperor Constantine in the fourth century.

How is it that in the West, Christian anti-Epicureanism flourished in the Middle Ages even though the Epicureans had totally disappeared by then?

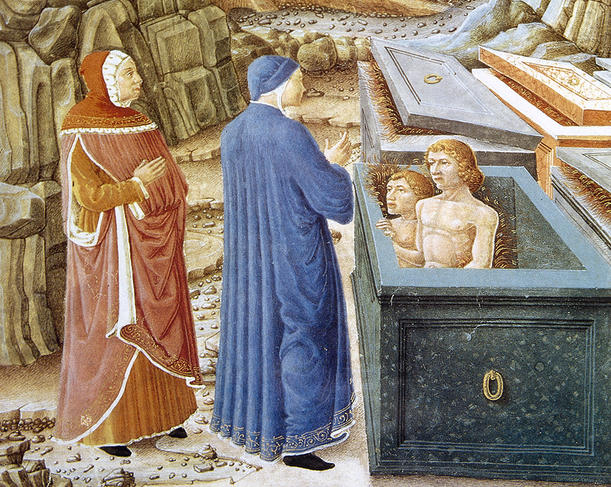

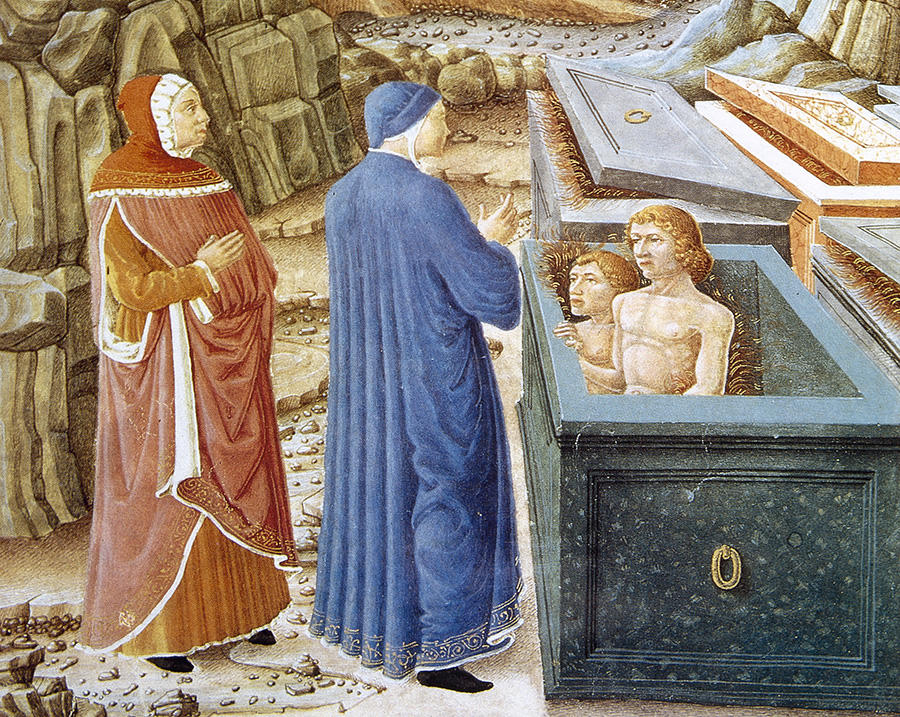

A.R.: My hypothesis is that many medieval theologians, for evangelical purposes, used the image – completely fictional – of the Epicurean enslaved by desire and living as though God did not exist. In other words, the gluttonous, hard-drinking character, totally devoted to pleasure in defiance of religion and thus destined to burn in Hell, served as a bogeyman conjured up in sermons in order to strike terror into the hearts of the faithful and prevent the emergence of heresies. To that end, they associated the ultra-negative image of the Epicurean with well-known Biblical figures. For example, to turn Epicurus into an atheist, they evoked the ‘fool’ of Psalm 52 who says in his heart, ‘There is no God’. In the early 14th century, Dante’s Divine Comedy also contributed to this anti-Epicurean rhetoric by making Epicurus the only ancient Greek philosopher present in the Sixth Circle of Hell, reserved for heretics.

That said, your essay shows that the rehabilitation of Epicurus dates from the Middle Ages, and not from the Renaissance, contrary to a still widely held belief…

A.R.: Indeed. For nearly 100 years it has been endlessly repeated that the chance rediscovery in the early 15th century, by an Italian humanist named Poggio Bracciolini, of De Rerum Natura (On the Nature of Things), a text by Lucretius from the first century BC containing an overview of Epicurean philosophy, enabled the return to grace of the Greek hedonist on the philosophical scene. This thesis is a myth. As paradoxical as it may seem, it was the Middle Ages that brought Epicurus out of the underworld, which quite simply went unnoticed until now due to the focus on texts (sermons, theological treatises, poems, etc.) that stigmatised Epicureans.

A close look at the medieval documentation on Epicureanism in all its facets shows that, starting in the 12th century, philosophers like Pierre Abélard, his follower John Salisbury or the learned Englishman William of Malmesbury, praised the excellence of Epicurus’ ideas, especially in the realm of ethics. In addition, the early 13th century saw the proliferation of collections of ‘Lives of the Philosophers’, some of which presented him as a model of morality, including for Christians. In my work I show that the clerics of the Middle Ages contradicted thaemselves. Although perfectly aware of the substance of Epicurus’ philosophy, they discussed it only within their own elite circles, while deliberately propagating a false image of Epicureans to the public, as a simple but effective fear tactic.

In your opinion, what would be Epicurus’ attitude towards the Covid-19 epidemic we are enduring?

A.R.: Since the health crisis has deprived us of a number of pleasures, making us unhappy, he would no doubt encourage us to reflect on our need for the joys and blessings that are now inaccessible, and to make the most of those that we still have. The man who founded his school outside the walls of Athens, and who advocated a secluded existence among friends, far from public affairs, would probably be a champion of today’s ‘neo-rurals’, eager to flee the locked-down cities!

Bibliography

Épicure aux Enfers. Hérésie, athéisme et hédonisme au Moyen Âge, Aurélien Robert, Fayard, 2021.

- 1. Aurélien Robert is a philosopher and CNRS research professor at the SPHERE laboratory (CNRS / Université de Paris). He was awarded the 2019 CNRS Bronze Medal for his body of work.

Explore more

Author

Philippe Testard-Vaillant is a journalist. He lives and works in south-eastern France. He has also authored and co-authored several books, including Le Guide du Paris savant (Paris: Belin) and Mon corps, la première merveille du monde (Paris: JC Lattès).