You are here

Latin graffiti are precious witnesses of the past

In the 7th century, at the dawn of the Muslim conquests, Greek was the language commonly used throughout the Byzantine Empire. In the eastern Mediterranean, Latin writing disappeared from the graphic landscape – but not completely. Gradually, until the Ottoman expansion in the 16th century, pilgrims, traders and crusaders from the West built hospices, churches and castles in the region, and on their walls left inscriptions and graffiti in the Latin alphabet. It was a way of taking possession of the premises in graphic, spatial and symbolic terms, in particular in the holy sites of Christianity.

Graffiti and inscriptions as historical objects

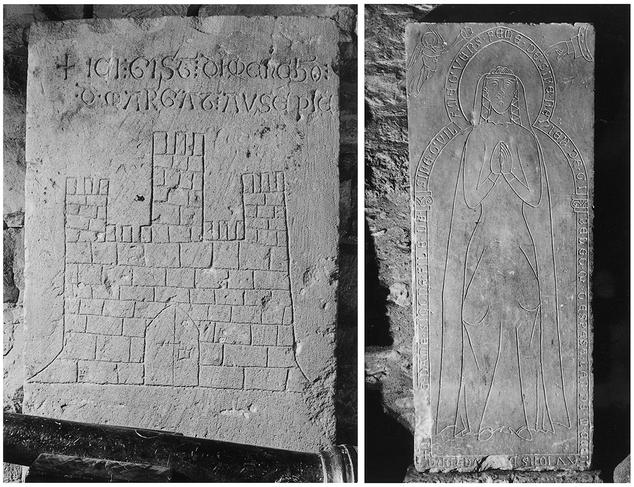

Immortalised in stone, metal or wood, thousands of these impromptu texts have survived to the present day. Unique testimonies of the short-lived Western presence over the centuries, these traces now serve as historical documents. While examples found in Europe have been extensively studied (notably the graffiti of Pompeii, in southern Italy), the Latin writings of mediaeval visitors to the Middle East have long been neglected by research in favour of manuscript sources. In the past few years, Estelle Ingrand-Varenne, a CNRS researcher at the CESCM centre for mediaeval civilisation studies1 seconded to the French Research Centre in Jerusalem (CRFJ),2 has been tracking down these texts, from scribbled graffiti to formal inscriptions.

At the origin and core of this project is a writing system: the Latin alphabet. In 2013 Ingrand-Varenne studied, as part of her thesis research, the epigraphy of western France between the 12th and 14th centuries and its transition from Latin to French. In the process she discovered that Roman-script inscriptions from that same period could be found in the Holy Land – modern-day Palestine and Israel. For a specialist in mediaeval epigraphic writing, “These traces are all the more important because in Israel, for example, they are the only written source from the Crusades of the 12th and 13th centuries that has survived in situ, in other words preserved in the same place where it was produced. Everything else – manuscripts, charters, etc. – has disappeared or been brought back to the West.”

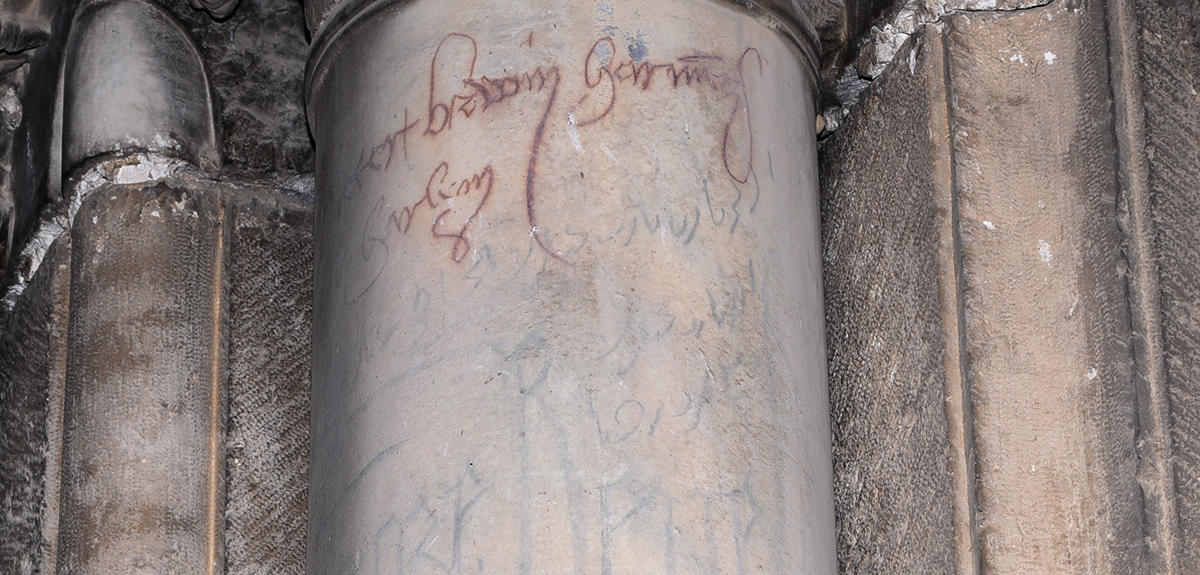

On a trip to Istanbul (Turkey), she began deciphering Latin inscriptions of Constantinople, from the period just after the 4th Crusade. “The Crusaders who settled there left some traces, including monumental writings in the decors of churches, in holy sites, on mosaics, or on paintings,” she recounts. “They may have inscribed a coat of arms, the names of the people depicted, short poems, and in many cases religious texts and prayers, in a world that still spoke Greek.” But how are we to understand them? What is their meaning? Whether isolated words or whole texts, Ingrand-Varenne and her fellow researchers of the Graph-East project have set out to study them as carefully as any historic oration.

Writing in holy places

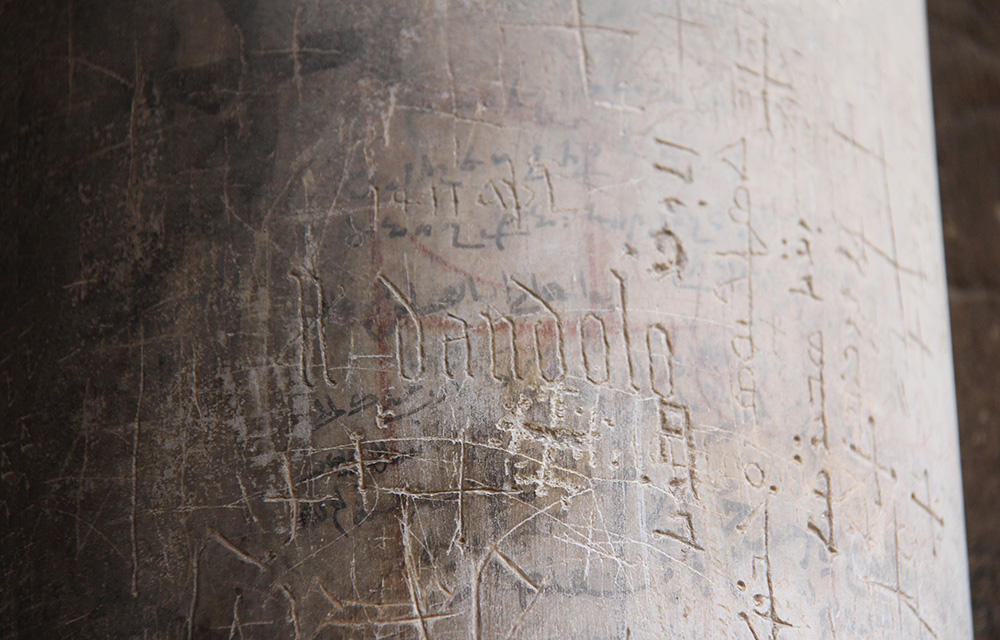

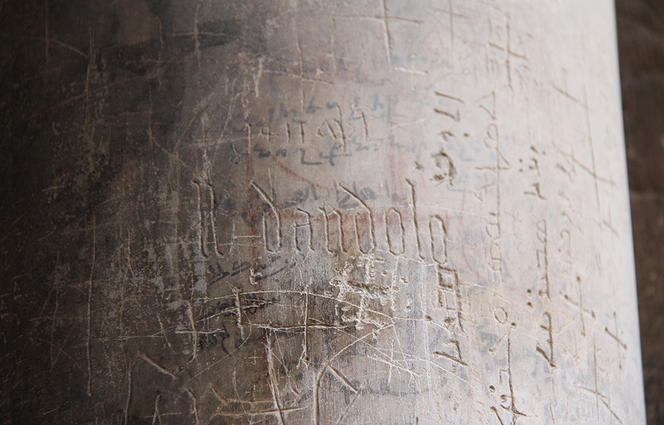

“Basilius pictor” (“Basil the painter”), signed the artist who created part of the mosaics decorating the Basilica of the Nativity in Bethlehem. “Cursed be he who takes me from the Monastery of the Holy Nativity of Bethlehem” can be deciphered on a candleholder – evidently a curse to discourage theft. Written, drawn or painted on the walls, these mediaeval inscriptions tell us something about the society that produced them. They reveal a social practice, a means of communication used to convey a wide variety of messages. They sometimes appear in the form of graffiti, including personal sentiments as well as crude scratches and drawings on walls and monuments, and occasionally as formal inscriptions with a commemorative connotation, in many cases commissioned by kings, men of power or more generally high-ranking clerics. “Graffiti, in particular, is a very strong gesture,” Ingrand-Varenne emphasises. “It’s a more ordinary kind of writing, left by pilgrims and travellers passing through. They wanted to leave their mark, their name, on a column or stone, in a place that is highly venerated in Christianity, no doubt as a way of commending themselves to God.”

For the first field mission – and the first phase – of the Graph-East project,3 the team headed for Cyprus. “The island has the eastern Mediterranean’s highest concentration of mediaeval inscriptions in the Latin alphabet,” Ingrand-Varenne explains. “There are more than 800, mostly funerary.” This monumental project is based on an inventory of some 2,500 previously identified inscriptions from all over the region, with the hope of finding many more. The Cypriot mission has allowed the researchers to gather precious data, and to compile a great many notes, translations and photographs. Their goal is to record the entire environment of these written vestiges in as much detail as possible. These new research logs will expand and enrich the already sizeable inventory of inscriptions. On their quest, Ingrand-Varenne and her colleagues will travel to ten countries, including Israel and the Palestinian territories, Turkey, Greece and its islands, Lebanon, etc. “We have identified very specific sites,” she reports, “like the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem and the Basilica of the Nativity in Bethlehem, one of the oldest churches in the world. These are major pilgrimage sites and rich sources of graffiti. The project is still in its infancy.”

Making the walls talk

Who wrote these inscriptions and why? The initial goal of Graph-East is to understand what this graffiti represented in the region during the Middle Ages, a period that lasted nearly ten centuries. “Beyond their meaning, we also explore the cycle of the epigraphic object, in order to identify and retrace its path up to the present day,” Ingrand-Varenne says. “In other words, how did these markings last over the centuries? Why is it still possible to see them today?” The second phase of the project will focus on the role of these writings and their interactions in an era when the Latin, Greek, Armenian, Arabic, Georgian and Syriac alphabets all coexisted. “Until now, epigraphs have been studied in a very isolated way. What we want to do, in this multicultural context, is propose an interconnected history.”

Lastly, the Graph-East researchers will also analyse the migration of these writings, from West to East, through the point of view of cultural transfers. To share the story of the field work, document the research archives, and even open new avenues for investigation, Graph-East will also be the subject of a documentary series:4 two videographers will follow the team throughout the entire five-year project. Through these unprecedented archives, the walls still have much to tell us about mediaeval societies.

To find out more The ERC Graph-East website: https://grapheast.hypotheses.org/

- 1. Centre d’Études Supérieures de Civilisation Médiévale – CNRS / Université de Poitiers.

- 2. International Research Laboratory (IRL – CNRS / Aix-Marseille Université / French Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs).

- 3. The Graph-East epigraphic project is the recipient of a European Research Council (ERC) Starting Grant.

- 4. To watch the documentary series on the mission in Cyprus: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UChAbTpXdLZ5y3j0ENCQ8SJw

Explore more

Author

Anne-Sophie Boutaud studies scientific journalism at the Université Paris-Diderot. She holds a degree in history and political science.