You are here

Art and the ages of life

From one society to another, are there differences in the artistic representations of youth, old age, and the different ages of life in general?

Jean-Marie Schaeffer:1 The role that a society ascribes to the different ages of life can be seen in the way they are portrayed: people represent what is important in their culture. There are constants and variations from one culture to another. Many of them pay close attention to childhood, no doubt because it is the starting point of human life. In ancient cultures, especially in Greece, young adulthood was the most important age. The gods were often young adults, which is an ideal representation. In fact, adulthood is a major phase of life in all societies, because it is the age of reproduction. It is associated with a lot of rituals, symbolism, etc. Unlike in the West, the societies of Eastern Asia highly value the representation of old age, a life phase that has always been granted special status in that part of the world. In traditional Chinese and Japanese cultures, for example, later life is when people develop their full potential as individuals.

You also explain that the number of ages represented in the arts can vary from one culture to another…

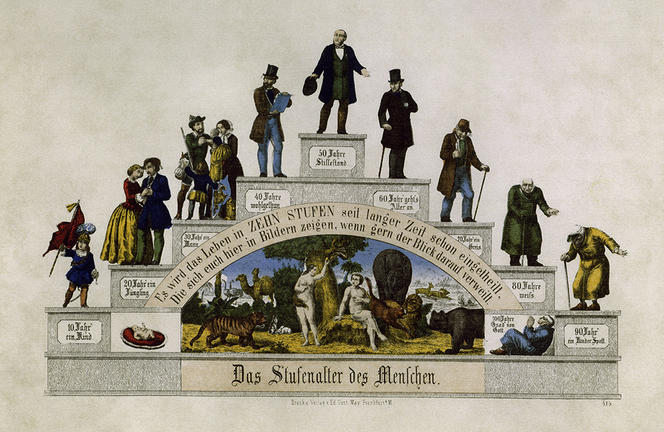

J.-M. S.: Indeed, each culture divides the biological continuum that ranges from birth to death according to classifications that are not of natural origin, but rather arise from the contingency of the development of cultural categorisations. The number of age groups represented varies a great deal across eras and societies, but there are two models whose differences are particularly striking: the representation in three ages and the stairway model. The classical distinction of three ages – infancy, adulthood and senescence – is shared almost universally and will always remain pertinent, because these stages describe the organism’s evolution. In all societies, this corresponds to three critical biological phases: birth, the age of reproduction and death.

At the other extreme, the stairway model offers a much finer, decidedly hierarchical view of the different ages. It usually comprises ten steps, each one representing ten years of life. Starting from birth, the stairway rises until adulthood, the peak, and then descends, ending with death. This model, which only exists in the West, is dominant today. It first emerged in the 17th century and can be explained in particular by the emergence of the concept of adolescence, as well as increased life expectancy: additional phases were needed in the representation of the ages…

Presuming that they are the reflection of our societies, artworks also play a role within them. What functions and impact can they have in the representation of the ages of life?

J.-M. S.: The first thing to consider is that there is an interaction between what seems at first to be a purely abstract classification and the social management of people’s lives. The artistic representations linked to the ages of life are targeted at individuals, always offering them a specific way of situating themselves within their own life path.

When they are standardised, these models can also lead to an optimisation of the political-social management of life stories. For example, the way in which people in their sixties are represented in films, paintings and novels can have an effect not only on these individuals’ own self-image, but also on the issue of the legal retirement age – 60 or up to 65. This debate has something to do with the fact that later life is now subdivided into many phases, and that the earlier ones are no longer really considered a part of old age.

Thus, the way people see themselves can make a difference: if they think they are still in the prime of life, they will more easily agree to keep working longer… There can, however, be discrepancies between how a certain age is commonly perceived and the actual situation in some segments of society.

In addition, all representations have ideological functions, among others, and this is also true of works of art. For example, the works of painters from the end of the Middle Ages, especially in the German tradition, demonstrate both a fascination with the age of reproduction and a sort of distaste for old age. While Venus and Eve are portrayed as young and idealised, the elderly, especially women, are represented as decrepit. This harsh vision of the life path is no doubt connected to Christianity, whose goal is to remind believers that their youth will not last, that they are perishable and destined to return to dust. The idea conveyed is that whatever exudes health and beauty is ultimately but an illusion, soon replaced by debility and death…

You have also studied people’s relationship with creativity over the course of their lifetime. How does it evolve?

J.-M. S.: Creative practices emerge in early childhood. In our society, all children draw, sing, tell stories… The fact of projecting mental content onto objects that can embody it is a part of cognitive growth. In the skills that they presuppose and deploy, these activities form the foundation of artistic creativity, which however disappears with age in most cases… There are far fewer adults than children who draw! This is due to the fact that the arts are not the only human endeavour that requires cognitive resources. While growing up, we have to choose our preferred areas, which is much less true during childhood (at least in our societies).

If all children have creative potential, how is it that some abandon artistic practices while others pursue them as adults?

J.-M. S.: There are two main cognitive styles among human beings: the convergent style, which is more practical, geared towards a search for solutions, and the divergent style, which is more intuitive and imaginative. The latter is more conducive to artistic practices. What distinguishes a poet from a normal speaker, for example, is the capacity to pay as much attention to the sound as the meaning of the words, to focus on different levels… However, these predispositions cannot be dissociated from social background. In certain circumstances, a cognitive style can be reinforced or, on the contrary, inhibited. For example, the traditional school, as it operates in our societies, discourages the divergent style, for the sake of educational efficiency, whereas a Montessori school might give children more opportunities to cultivate that aspect of their personalities.

Do artistic practices also evolve as one ages? And what is the perception of old age in relation to creativity?

J.-M. S.: For a long time, art historians and critics have viewed later life as the time when artists began to repeat themselves. Yet some of them drastically change their style when they become older, often producing freer work than when they were younger. One example is Titian, whose way of painting was radically different as an old man. But no matter these discoveries on the style of old age, the current Western conception sticks to the conventional view that mid-adulthood is the golden age of creativity.

In order to break into the international art scene, it seems that artists have to do so increasingly early. If they haven’t made it by the time they reach 40, they can forget it! So if Kandinsky, who started painting at that age, wanted to make a career today, he would find it hard to be accepted by the institutions.

As I mentioned earlier, things are different in Asian societies, which have a positive view of late life. In Chinese art, for example, an artist does not achieve greatness until then. But now that art has become globalised, this does not correspond to the dominant representation of the development of creative power through the different stages of life.

In terms of the reception of artworks, are there differences from one age group to another? You have taken a particular interest in the case of children…

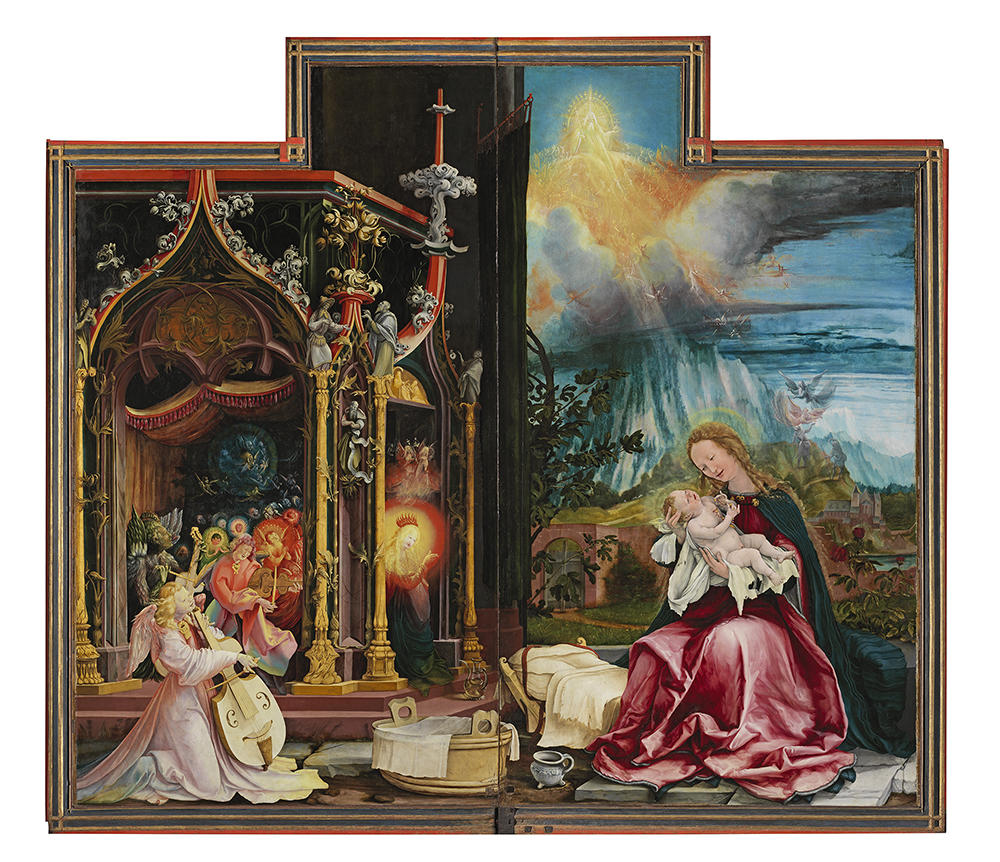

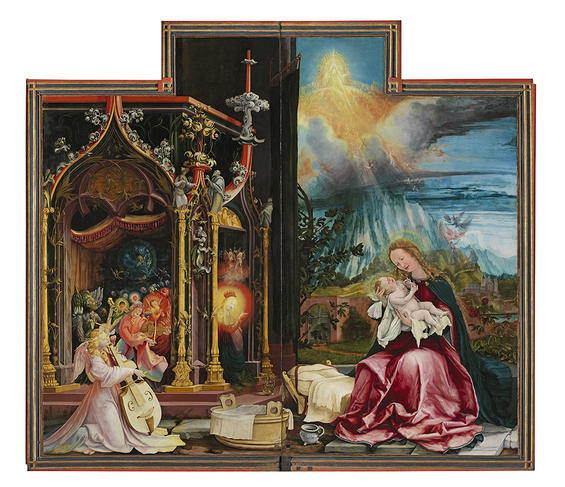

J.-M. S.: For a long time the focus was on experience in adulthood, which was upheld as the standard for proper receptiveness. But we have seen that children also have very complex reactions to art! In fact, they do the same thing as adults: they try to understand. But they do it differently. As part of a study entitled “Creation, Cognition, Society” conducted by Michel Menu, Pablo Fontoura and myself, based on a work by Grünewald,2 we were able to determine that the children paid much more attention to colours and focused more on details than on the whole picture – which often remained unclear to them. They do not have the knowledge or integrative perception that adults have, so they use whatever means they can.

In your opinion, children enjoy greater freedom and spontaneity than adults…

J.-M. S.: Yes, because children are not so acculturated. It is true that they miss some elements, but they make up for it with a freedom regarding art that adults no longer have. This can be observed in their respective responses to questions about a work of art. Adults are often very self-conscious. If they think they might not have understood something properly, they don’t talk about it, limiting themselves to what they think is an acceptable answer. In a way, this idea that we must always rise to the occasion and maintain our social capital cripples our perception. Many adults do not really look at the artworks – they don’t discover anything, but rather recognise a sign. Of course there are exceptions, true connoisseurs… This also very much depends on the status of the art under consideration. Unlike painting, it’s easier for people to express their tastes in cinema, for example, which is a less hierarchical art form. Even in France, a country traditionally well-informed in the field, people feel that they can give their opinion without having to conform to a norm. The same is true for so-called “popular” music, which is discussed much more freely. The Internet also enables a different dynamic, even for the other arts. The proliferation of websites on which people can give their views anonymously, using a pseudonym, is liberating.

Did people in the past have a different perception of artworks?

J.-M. S.: It is very difficult to know what viewers’ perceptions were like in the past, because artworks were usually not placed in a separate category or intended for a particular experience. In many societies, for example here in Europe in the Middle Ages, paintings were displayed in churches and had a votive function. It is true that they triggered the same kind of perceptive and mimetic experience then as they do now, but that experience was not conceptualised or evaluated, and perhaps not appreciated in its own right, because what really mattered was the function fulfilled by the work of art. For example, Grünewald’s altarpiece, depicting the Crucifixion, sought to raise the morale of sick people suffering from ergotism.

- 1. EHESS research director, CNRS research professor emeritus, Centre de Recherches sur les Arts et le Langage (CRAL – CNRS / EHESS). Schaeffer has served as scientific director of the IRIS strategic interdisciplinary research initiative “Création, Cognition, Société” at Université PSL.

- 2. Matthias Grünewald, the Isenheim Altarpiece, Crucifixion (1512-1516). The Unterlinden Museum, Colmar, France.