You are here

Why the “Gulf Stream” is a misnomer

In your opinion, we shouldn't refer to the warm current that washes the coasts of Europe as the Gulf Stream. Why is this term, which is still very widespread, a misnomer?

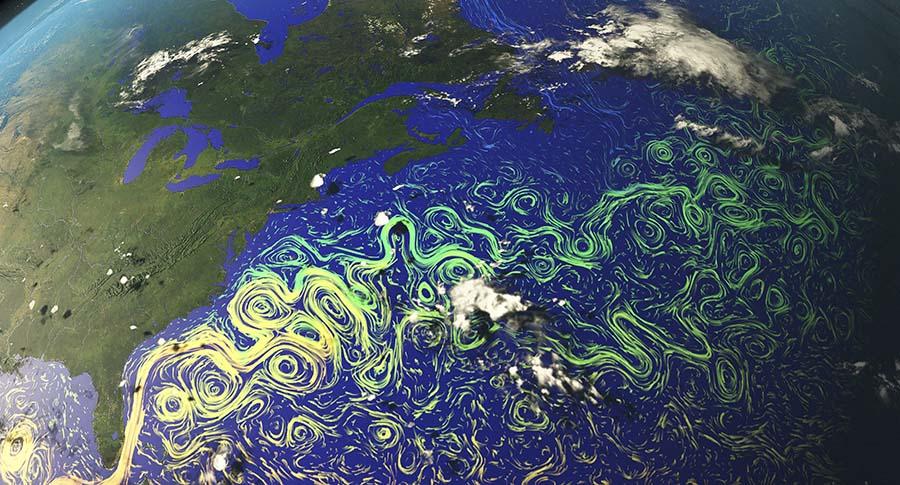

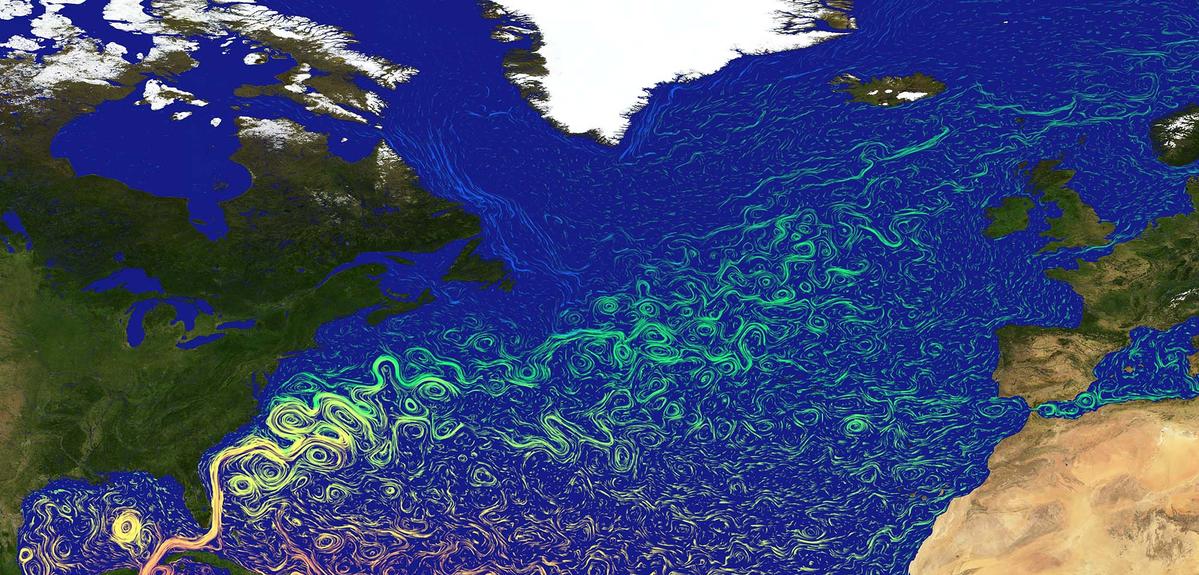

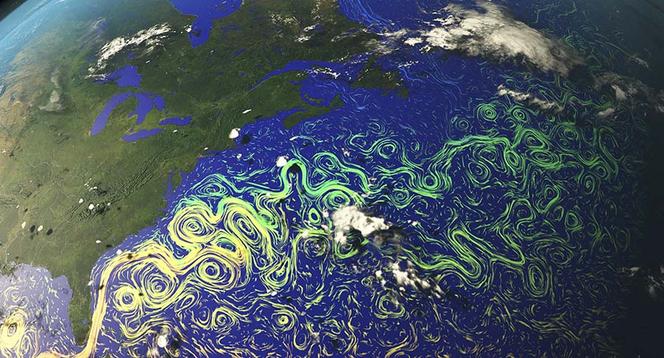

Julie Deshayes:1 The Gulf Stream is a warm ocean current that has been well known since the sixteenth century, as it was used by seafarers returning from the Americas. Until the arrival of the first satellites, it was described as a single continuous stream flowing from Florida (US), where it originates, to Europe and the polar latitudes. We now know that this is not the case: although the Gulf Stream is indeed a continuous, extremely strong current that flows northwards along the coastline of the United States under the effect of the Earth's rotation (it is part of a larger system called the North Atlantic Gyre), scientists have discovered that after breaking away from the coast at Cape Hatteraas, North Carolina (US), it totally changes its appearance, breaking up into a series of ocean eddies that are clearly visible to satellites. Some of this water – around 20%, which is roughly twenty times the discharge of the Amazon – crosses the Atlantic basin from west to east and continues northward, while the rest returns southward.

In addition, a well-identified south-north current is observed off Newfoundland (Canada), which again breaks into small vortices as it heads out to sea. So it is not the Gulf Stream that washes the European coastline, but rather a series of currents and eddies. These have been combined mathematically and dubbed the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, or AMOC.

Where does the term ‘Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation’ (AMOC) come from?

When it has crossed the Atlantic and reached the southern tip of Greenland and Norway, this warm water cools down. Since it has become much denser, it sinks to the bottom and flows back across the Atlantic basin in the direction of Florida. It is this process that is known as overturning circulation. It often used to be referred to as the ocean ‘conveyor belt’, but this term has fallen out of use today, since it gives the misleading impression of a single, continuous flow.

What role does the Atlantic Overturning Circulation, in which warm water flows up from the equator towards the poles and cold water moves down from the poles towards the equator, play in the global climate?

J. D.:This circulation loop across the Atlantic basin is crucial to the global climate system, because it enables the excess heat received at the equator to be transported towards the poles. For lack of sunlight, the Arctic receives less heat than the equator, although every region of the planet, at all latitudes, reflects more or less the same amount of energy back into space (Editor's note: this is known as the albedo effect). As a result, the Arctic, which absorbs less energy than it radiates, has a negative balance, whereas the equator enjoys a surplus. The Atlantic Overturning Circulation, which the general public and some of the media improperly call the Gulf Stream, enables this heat to be more evenly distributed around the globe. Scientists now believe that it played a key role in the transition from the last glacial period, during which part of Europe was covered with ice, to the interglacial period that we have experienced over the last 10,000 years, with its more temperate climate.

Is the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation slowing down due to climate change, as was again recently reported in the media?

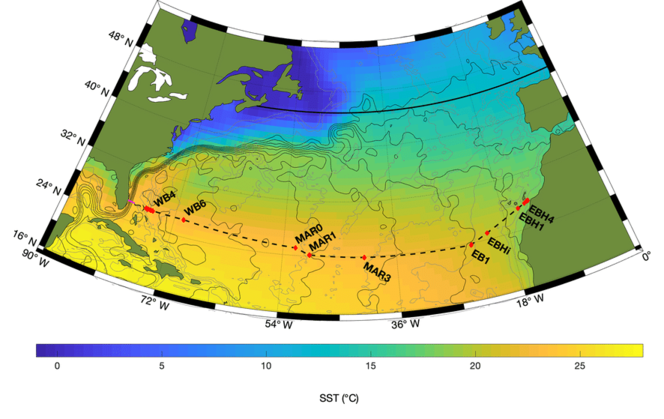

J. D.: Although we have been measuring the strength of the Gulf Stream for the past forty years, the Atlantic Overturning Circulation has only been directly monitored since 2004. Earlier data is based on estimates obtained through indirect and often disparate methods, for example by studying sediment cores taken from the ocean floor. Today, some thirty sensors located along a line connecting Florida to southern Morocco, at a latitude of 26° North, have helped fill this gap. Since the AMOC is not a single stream, but rather the combination of numerous currents and eddies, a mathematical operation is necessary to obtain these figures: all the currents flowing back southwards across the 26th parallel are subtracted from the flow of the Gulf Stream measured at a given time.

Today we have a data set that covers a mere fifteen years. This is not enough to provide us with long-term trends, especially since the Atlantic Overturning Circulation varies considerably from one month to the next. One-year averages show two periods: from 2004 to 2015, the AMOC weakened, whereas it has been gaining in strength again over the last five years. It is difficult to draw any conclusions at this stage. We need to continue taking measurements and refine them by deploying new instruments at other points in the Atlantic.

And what does the indirect data collected prior to 2004 say about this possible slowdown?

J. D.: A paper recently published in Nature Geoscience that reviews the last thousand years points to a slowdown since the late nineteenth century. That would therefore coincide with the development of our industrial societies and with an increase in greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. Although great care should be taken when interpreting these results, which come from a wide variety of different studies and methods, it is nonetheless possible that the AMOC will slow down over the next hundred years, and has perhaps already started to do so. This is also predicted by a number of current climate models. Indeed, some scenarios even mention the possibility that the Atlantic Overturning Circulation might come to a complete halt. But, yet again, scientists need to keep accumulating data in order to refine these projections.

If the AMOC were to slow down or even stop, what impact would this have on the climate in Europe?

J. D.: First of all, it is important to realise that the AMOC is not directly responsible for our relatively mild winters, as compared to those in Canada at the same latitude. The AMOC, and even further upstream, the Gulf Stream, simply warm the North Atlantic Ocean; it is the prevailing westerly winds that blow over it and warm up on contact with it that bring us air that is not as cold as might be expected. As for the impact of a weaker AMOC on Europe's climate, here again it is difficult to say, because there are a huge number of variables involved. One thing is certain: it won't make Europe cooler, since human-induced global warming is far too powerful to be overridden merely by the slowing down of a marine current in our latitudes. On the other hand, a slower AMOC could cause more episodes of severe weather in winter, combined with very intense droughts and heat waves in summer. Finally, it should be remembered that, although some of today’s climate models predict that the AMOC may come to a stop, this will never be the case of the Gulf Stream, which flows along the US coastline and is exclusively related to the Earth's rotation. This is not true of the AMOC, which to a large extent, is linked to the Earth's energy balance and to the circulation of warm and cold water between the equator and the poles.

- 1. Julie Deshayes is a researcher at LOCEAN oceanography and climate laboratory (CNRS / MNHN / IRD / Sorbonne Université).