You are here

Solar storms ahead

Reading time: 10 minutes

The most powerful solar storm since 2023 has hit Earth on 19 January 2026, giving rise to spectacular polar lights. This is the latest phenomenon of a series that has been impacting our planet over recent months.

Already on the night of 10 to 11 May, 2024, French skies were lit up by a glowing reddish veil, which, in some places, displayed a green border near the horizon. Visible even in the south of the country, these dazzlingly coloured displays were the subject of countless images posted on the social networks by awestruck onlookers. Amazingly, this was in fact an aurora borealis, (also known as the northern lights)1, normally confined to the regions near the poles, but on this occasion occurring at unusually low latitudes. This exceptional event was due to the fact that over the past few months, the Sun has been going through a period of intense activity, characterised by a proliferation of solar flares on its surface. This directly impacts our planet in the form of extreme magnetic storms, of which the aurora borealis is the most spectacularly visible manifestation.

A cycle that began in 2019

Our star constantly switches between relatively quiet phases and periods of greater activity. These variations follow a cycle lasting between 10 and 13 years. Evidence for this periodicity comes in particular from the monitoring of sunspots, which has been carried out since the mid-18th century. On the basis of these meticulous observations, we now know that the Sun has already gone through 24 solar cycles since 1755, and that a 25th cycle that began in 2019 is probably about to reach its peak. This is borne out by the presence of over a hundred sunspots on its surface, whereas only a handful are visible during periods of low activity.

"These regions, which appear darker because they are several thousand degrees Celsius cooler than the surrounding material, are associated with sudden surges of the magnetic field circulating inside the Sun, which breaks through its surface, as it were," explains Alexis Rouillard, a CNRS researcher at the IRAP institute of research in astrophysics and planetary science2 in Toulouse (southwestern France). "The complexification and intensification of the magnetic field directly above clusters of sunspots are the cause of solar storms, in which plumes of charged particles, namely electrons and protons, are ejected at speeds ranging from several hundred to several thousand kilometres per second." Such storms can take from one to four days to travel the 150 million kilometres or so between the Sun's surface and the outer boundary of the Earth's magnetic field.

At the end of their journey, the ionised particles ejected by the Sun collide with the Earth's magnetosphere, causing it to reconfigure. As they travel along this rearranged magnetic field, some of the charged particles are carried back to the ionosphere, the upper layer of the atmosphere, where they come into contact with molecules of oxygen and nitrogen. When the solar storm interacts with the Earth's magnetic field, it turns into a geomagnetic storm.

Geomagnetic storms and risks to infrastructure

As Rouillard explains, auroras are in a way the result of this encounter. "When the atmosphere's molecules, atoms and ions are impacted at high speed by the electrons transported by the geomagnetic storm they become temporarily excited. To return to their initial energy level, the excited atoms emit light whose colour depends both on their nature and on the composition of the upper atmosphere." At altitudes above 200 km, red light is produced by the excitation of oxygen, which is mainly present at the top of the atmosphere. Between 100 and 200 km, the same chemical species produces blue and green hues. Below 100 km, purple results from the interaction of the electrons with molecules of nitrogen, which are concentrated in the lower atmosphere.

However, the spectacular display of the northern lights masks a more disturbing picture. In our increasingly technology-driven world, solar storms can have a huge impact on human activities. Space X learned this the hard way: in February 2022, it lost 40 Starlink telecommunications satellites while placing them into orbit. Although the company did not specify the reasons for this failure, it is highly likely that a geomagnetic storm was involved, since the accelerated particles release some of their energy into the upper atmosphere, thus raising its temperature and causing it to expand.

"Since they didn't foresee the onset of this storm, the speed allocated to the satellites to enable them to reach their final orbit proved insufficient to allow them to get them through this region of the atmosphere, which had become denser, causing them to fall prematurely back to Earth," confirms Jean Lilensten, a CNRS research professor and astronomer at the Institute for Planetary Sciences and Astrophysics of Grenoble (IPAG)3. Some believe that this expansion of the atmosphere could even throw some of the space debris orbiting our planet off course. With ever-increasing amounts of debris (currently 34,000 fragments over 10 cm in size), there is likely to be a greater risk that, in the event of a solar flare, one of these objects, travelling at more than 28,000 km/h, could collide with a satellite.

Geomagnetic storms also alter the distribution of electrons in the atmosphere, which can interfere with the signals broadcast by GPS satellites that drivers use to know the exact position of their vehicles. This was the plight of hundreds of farms in the Midwest (United States) during the solar storm of May 2024, when the GPS navigation system that enables tractors to optimise the sowing pattern on these huge plots of farmland suddenly broke down as a result of electromagnetic interference.

Certain strategic industries can also be disrupted by induced geomagnetic currents that form on the Earth's surface as a result of rapid changes in the magnetic field caused by geomagnetic storms. This can affect everything from oil pipelines to undersea telecommunications cables, oil drilling, and electricity generation and transmission systems. In March 1989, for example, six million people in Quebec were plunged into darkness for nearly ten hours following a massive failure of the Canadian province's electricity grid.

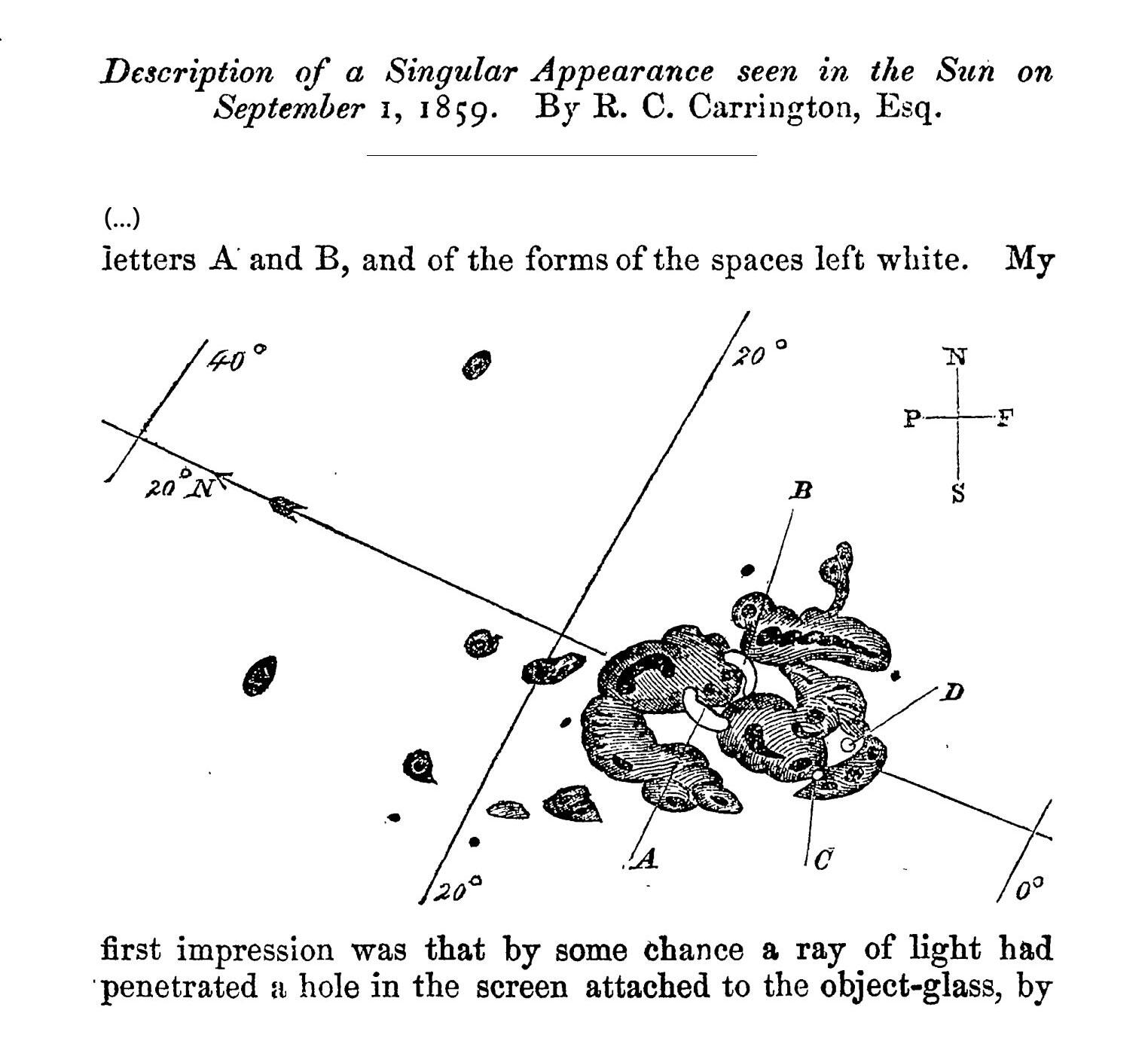

A major episode every 150 years

However, the most powerful solar storm ever recorded to date is still that which took place in the summer of 1859, also known as the Carrington event4. The episode, three times more intense than the one we experienced last spring, massively disrupted telegraph communications, even causing some equipment to burst into flames. "In a report published in 2013, American researchers estimated that a solar flare of this magnitude would cause between 600 and 2,600 billion dollars' worth of damage if it happened in today's technologically advanced world," Lilensten points out.

Given that solar storms of this strength occur on average every 150 years, the possibility of an event of this magnitude happening in the near future cannot be totally ruled out, although there is no way of knowing exactly when it will happen. This is because, astonisingly, scientists are still unable to predict exactly when the Sun's activity peaks.

"At the moment, we are incapable of anticipating with any certainty whether an active region on the Sun's surface will trigger a geomagnetic storm, or how intense this hypothetical event will be," Rouillard admits. Given that the solar flare that caused the geomagnetic storm of 1859 took a mere 17 hours to reach Earth, as compared to two days for that of 10 May, 2024, being able to foresee such an eruptive episode would leave just enough time to protect our planet’s most sensitive facilities by shutting them down.

A peak of activity in early 2025

One thing is certain: solar storms will be getting more powerful over the next few months. "As we approach the peak of the cycle, new clusters of sunspots will form ever closer to the Sun's equator," Lilensten warns. "Since this concentration of sunspots in the equatorial region is characterised by an accumulation of energy, the flares likely to occur there will have a greater probability of impacting our planet."

To monitor the Sun's activity as closely as possible, the scientific community has, over the past twenty years, developed a network of both ground-based and space observatories, including the American Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO) satellite. Equipped with very high-resolution sensors, the observatory, which is placed in a geosynchronous orbit 36,000 km above the Earth, continuously monitors changes in the magnetised surface as well as in the highly dynamic corona located at higher altitude.

Improved monitoring capabilities

However, improving forecasts of solar storms, and therefore being better prepared for the risks they pose to human activities, requires to massively increase our capacity to monitor the Sun. With this in mind, specialists from the French Organisation for Applied Research in Space Weather (OFRAME) are planning to expand the existing array of probes and sensors based on Earth or in its near-space environment that measure electromagnetic fields and particles. This research programme could be further enhanced through the deployment of microsatellites designed to monitor the upper atmosphere and magnetosphere. "The idea is to adapt terrestrial weather modelling methods, which are principally based on an abundance of measuring points, to the Earth-Sun environment," explains Rouillard, who co-directs OFRAME. Numerical models that simulate the propagation of solar winds and storms heading towards Earth in order to forecast geomagnetic storms are also being developed as part of the Solar Terrestrial Observations and Modelling Service (STORMS) programme.

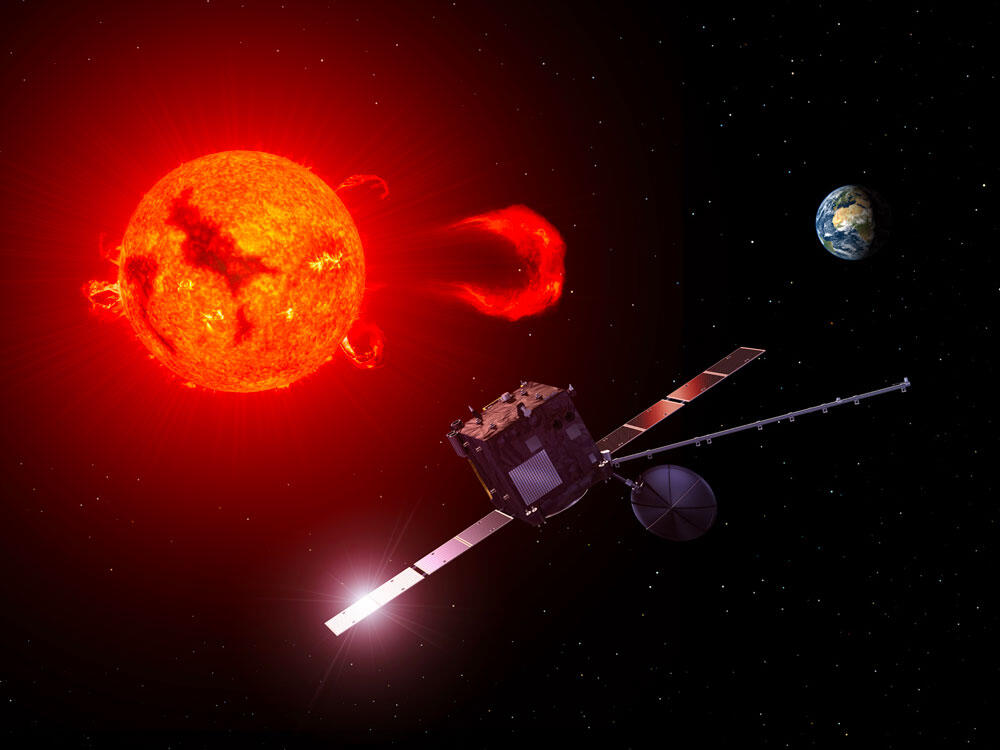

By 2031, the European Space Agency (ESA) plans to place a space weather observatory at point L5, an observation point located off the Sun-Earth axis. Whereas a telescope in orbit around the Earth, like the American SDO satellite, only provides a head-on view of solar storms, an instrument at this strategic point would enable a side-on view of such events. From this unique position, ESA's future satellite, dubbed Vigil, will be able to spot the slightest hint of a flare on the Sun and follow the propagation of solar storms towards our planet right up to the moment of their impact with the Earth's magnetic field.

The emerging discipline of space weather

We are thus witnessing the emergence of a new discipline, space weather, at the service not only of the scientific community but also of businesses, who are showing keen interest. Although it is not yet possible to precisely predict the onset of a solar storm, once it is underway the moment at which its effects will be felt on Earth can henceforth be accurately estimated.

Further initiatives are aimed at disseminating knowledge about space weather. This is the mission of the COMEA space weather operational centre5 launched in November 2023 in the French Alps. COMEA aims to produce space weather forecasts for the general public in the near future. "Thanks to bulletins issued every week on TV, radio and in the press, the aim of our project is to raise awareness of the nascent discipline of space weather, while at the same time popularising the science involved in monitoring the Sun," says Olivier Katz, co-president of the AurorAlpes association and a forecaster at COMEA. ♦

- 1. The term aurora borealis is used when this phenomenon occurs in the northern hemisphere, and aurora australis when it appears in the southern hemisphere.

- 2. CNRS / CNES / Université Toulouse III - Paul Sabatier.

- 3. CNRS / Université Grenoble-Alpes.

- 4. The name refers to the British astronomer Richard Carrington (1826-1875), who described this solar storm.

- 5. COMEA is supported by the IPAG institute of planetary science and astrophysics in Grenoble (southeastern France), the Grenoble-based Observatory of Earth Sciences and Astronomy (OSUG), and the AurorAlpes association.

Explore more

Author

After first studying biology, Grégory Fléchet graduated with a master of science journalism. His areas of interest include ecology, the environment and health. From Saint-Etienne, he moved to Paris in 2007, where he now works as a freelance journalist.