You are here

Science fiction throws light on the present

How can we coexist with other life forms? That is the question raised by the American author Ursula K. Le Guin throughout the Hainish Cycle. In this series of science fiction novels and short stories, humanity attempts to create a shared political organisation with extraterrestrials from all over the universe. Although all of these populations – including humankind – were originally interrelated, they have become extremely different from one another in terms of anatomy, intelligence, culture, language and lifestyle.

One example is The Left Hand of Darkness (1969), in which an Earthling lands on a planet whose inhabitants have no individual sexual identity. This divergence has multiple consequences for their family and social organisation. For one thing, the concept of seduction as well as gender-based aggression and rape are virtually non-existent. The effort and expense of parenthood are shared by everyone. Le Guin even suggests that the absence of sexuality also prevents conflict and war. In comparison, the human settler, whose is purely masculine, is seen as a sort of morally perverted monster… The mutual lack of understanding threatens the potential for cohabitation.

Transformative scenarios

“In other of le Guin’s tales, like The Word for World is Forest (1972) or The Telling (2000), some populations represent an industrialised, scientific humanity, while others have evolved in the opposite direction, cultivating closer bonds with nature and non-humans in general,” notes Anne-Caroline Prévot, an ecologist at the CESCO1 and scientific coordinator of the CSF.2 The question is always: ‘How can all of these very different life forms forge relations?’”

This theme finds resonance in today’s political issues, such as that of restoring the links between humankind and its environment. “In the old days children spent a lot of time outdoors, sitting on the grass surrounded by plants, insects and other animals,” Prévot points out. “Yet ‘nature experiences’ have become rare and quite different, despite their proven benefits for our physical and intellectual development, our health and our understanding of the world.” According to the ecologist, this change affects our capacity to apprehend the climate crisis and the extinction of an ever-growing number of species.

For this reason, the CSF proposes to examine social issues from both a scientific research and science fiction perspective. Every year since 2018, irrespective of the contingencies due to the COVID-19 pandemic, some 30 university students have been exploring topics like “restoring biodiversity in the city”, “the future of food” or “interspecies communication”. After reviewing the current state of knowledge, with the help of researchers and academics, they create science fiction works in cooperation with professionals in the fields of animation and artistic production.

Beyond its educational and entertainment value, this approach promotes “the development of new transformative scenarios”, Prévot adds. “If we want to reach the sustainability goals defined by the United Nations to ensure a viable environment in the medium to long term, we must radically change the way we see our relations with others and with nature.” This is in fact one of the key recommendations of the 2019 report by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), following the lead of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). “Imagination and fiction can help,” the researcher maintains.

Climate fiction

With the world facing an ecological crisis, nature and climate are everywhere in contemporary science fiction. They even have their own genre: climate fiction, or “cli-fi” – which depicts the consequences of climate change. One example is Exodes (2012) by the novelist Jean-Marc de Ligny, in which the Earth is doomed to imminently become uninhabitable. The novel’s six main characters wander from place to place, seeking a solution or a sense of meaning… “Not all cli-fi stories are that pessimistic,” notes Simon Bréan of the CELLF.3 “But the underlying idea is to use fiction to raise awareness of what could actually happen.”

In fact, the cli-fi genre only partially overlaps with science fiction. In Barbara Kingsolver’s 2012 novel Flight Behavior, a woman comes across a swarm of magnificent monarch butterflies in a valley in Tennessee (USA). However, the beauty of the phenomenon has a dark side: the species cannot survive the North America winters and should have been migrating to Mexico. Taking a realistic, scientifically sound approach, the author highlights a possible effect of global warming in the near future, and the more or less informed political initiatives that could ensue.

“Every era has its own concerns, and comes up with its own narratives in response,” Bréan says. “The other major, recurring theme today is the preservation of humanity in an increasingly computerised and robotised world.” The idea harks back to the earliest science fiction stories, like Karel Čapek’s play R. U. R. (1920), which depicts a rebellion of slave robots against their human masters, or even Mary Shelley’s novel Frankenstein or the Modern Prometheus (1818).

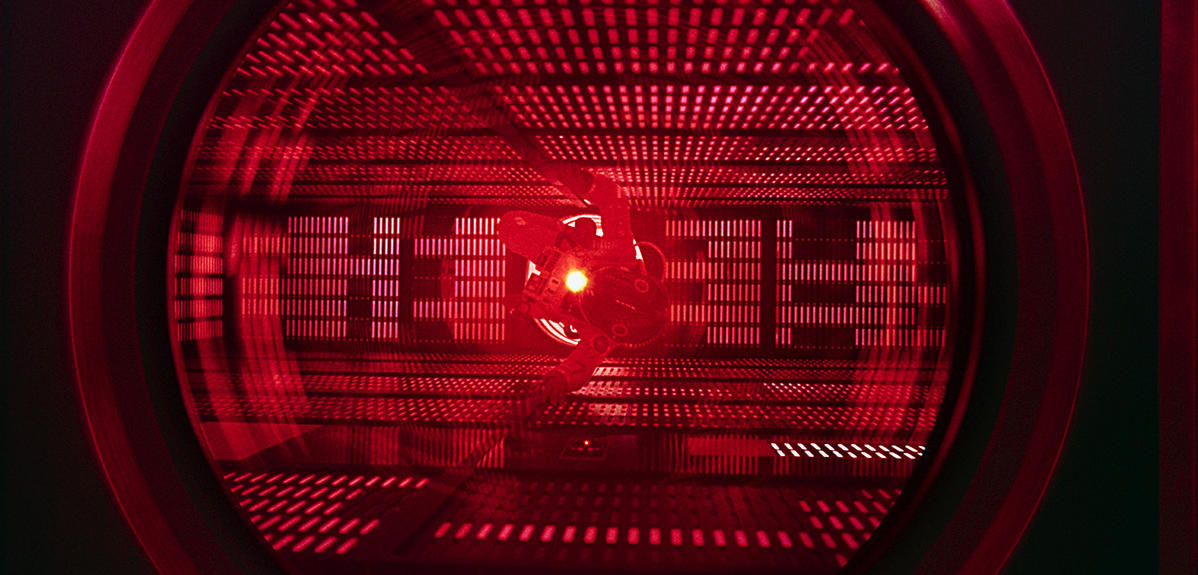

The idea of human preservation was also popularised in the late 1960s by the film 2001: A Space Odyssey, directed by Stanley Kubrick and co-written with the novelist Arthur C. Clarke.4 Every time humans create a technology that is supposed to be helpful and submissive, it ends up threatening their existence. “Today’s publications are not quite in the same vein,” Bréan adds. “They more often raise the question of human augmentation in machine form, in artificial intelligence systems, or the automation of human lives.” In her first novel After® (2021), Auriane Velten imagines a machine-dominated, dogmatic society that has replaced, since time immemorial, humanity as we know it.

The end of times

This theme is increasingly popular in an age of pervasive computerisation and digitisation. The idea of resisting, or rather finding the optimal balance in relation to technoscience, has emerged less than 15 years ago in the novels of Alain Damasio, Roland C. Wagner and Olivier Paquet. “Science fiction is often one step ahead of its time,” Bréan observes. In the 1950s, well before the first missions to the Moon, space exploration and the conquest of other planets formed a “dominant paradigm”. The question “How do we want to live?” dominated science fiction in the following decade, seeming to herald the imminent cultural upheavals. “As it happened, in the 1970s, the concerns of the day and the topics explored in science fiction tended to converge: a great many political questions were raised about the new kind of society that could be established, in the form of utopias and dystopias.”

Transversely, the theme of the apocalypse or the end of the world seems to be a recurrent obsession. “First of all for a very down-to-earth literary reason: it lends itself to faster-paced, more exciting plots,” notes Jean-Paul Engélibert, a professor of comparative literature at Université Bordeaux-Montaigne. “But above all it’s a way to confront our fears and anticipate what could happen should they actually come true.”

According to Engélibert, fictional accounts of the apocalypse, whether in science fiction or other literary genres, have always had a dual “heuristic and cautionary” function, shedding light on the present while sounding the alarm bell against potential worst-case outcomes. “Historically speaking, we could trace tales of the apocalypse back to biblical texts and even beyond. But the 19th century saw their meaning diverge from the religious scenarios to become secular.”

To cite one example, in The Last Man (1805) by Jean-Baptiste Cousin de Grainville, the progressivism of the Enlightenment is indicted – even though it encourages major works and gives rise to a new society – for causing the end of humanity. “This theme is not specific to science fiction,” Engélibert emphasises. “A similar idea can be found in romanticism, for example.”

Back to the present

The second half of the 20th century saw a surge of post-apocalyptic narratives. “The nuclear bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki , compounded by the context of the Cold War, gave rise to a generalised fear of the world coming to an end,” Engélibert says.

From Godzilla to Planet of the Apes to the novels of J. G. Ballard, it seems to be a given that humanity has acquired the power to destroy itself, and in the process to wipe out every other form of life on the surface of the Earth. Today this theme echoes the scientific and academic research on the “Anthropocene”, i.e. the idea that we have entered an era in which humankind is modifying the history of the planet, its geology and ecosystems. “Moreover, we are living in what the historian François Hartog5 calls ‘presentism’,” Engélibert adds. “We feel as though we can no longer learn from the past, because it seems too different to draw lessons from it in the current circumstances.”

At the same time, the future looks too uncertain and impossible to predict, in particular because we have abandoned the idea that progress will inevitably prevail. “Consequently, we are doomed to feel our way in the present, with no stable historical reference points and no reliable capacity for anticipation,” the researcher concludes. Resorting to fiction, whether in books, films or video games, offers a compromise for thinking about the apocalypse before it actually occurs, and understanding what is happening while there is still time to take action.

- 1. Centre d’Écologie et des Sciences de la Conservation (CNRS / MNHN /Sorbonne Université).

- 2. Comité de science-fiction, an initiative backed by the Institute of Environmental Transition Sorbonne Université, of the Sorbonne Université Alliance.

- 3. Centre d’Étude de la Langue et des Littératures Françaises (CNRS / Sorbonne Université).

- 4. The film is based on a script co-written by Stanley Kubrick and the novelist Arthur C. Clarke, partly inspired by two of Clarke’s short stories: “Encounter in the Dawn” and “The Sentinel”.

- 5. Center for Historical Research (CRH – CNRS / EHESS).

Explore more

Author

Fabien Trécourt graduated from the Lille School of Journalism. He currently works in France for both specialized and mainstream media, including Sciences humaines, Le Monde des religions, Ça m’intéresse, Histoire or Management.