You are here

The Turbulent History of the Suez Canal

When did the idea to dig a canal across the Isthmus of Suez emerge?

Caroline Piquet:1 The project to connect the Red Sea to the Mediterranean in order to facilitate trade between the two is an age-old concern, dating back to ancient Egypt. Beginning with the reign of Senusret III in the early second millennium BC, a system of canals connected the Red Sea to the Nile Delta. These canals were filled in for good in the eighth century AD.

The idea re-emerged on a number of occasions. The Republic of Venice considered it in the sixteenth century, before abandoning it for technical reasons. Under Louis XIV, Colbert also studied the question, in an attempt to open a new route to the Indies. But the true birth of the current canal dates back to Bonaparte's campaign in Egypt in 1798. Topographical measurements conducted by the scientific mission that accompanied the expedition laid the foundation for the first feasibility studies for opening up the isthmus.

The plan was revived in 1846 by a scholarly society founded by Saint-Simonians, who were unable to convince Egypt. In the end it was Ferdinand de Lesseps, a French diplomat who was very close to the Viceroy of Egypt, who obtained authorisation in 1854 to set up the venture that would build the canal and enjoy operating rights for a period of 99 years: the Suez Canal Company.

Does this mean that the Suez Canal Company was a French undertaking?

C. P.: The canal company was registered under Egyptian law, at least on paper. In terms of its capital, de Lesseps wanted international financing that would have included the Ottoman Empire, Great Britain, and the Austro-Hungarian Empire, among others. However, Britain looked unfavourably upon this project, which would create competition for trade with the East, and therefore refused to participate, as did the Ottoman Empire, of which Egypt was a part. Lesseps thus had to lower his sights, as the capital was primarily provided by small French shareholders, with the remaining 44% being financed by the Viceroy of Egypt. But Egypt went bankrupt in 1875 and had to sell its shares, which were bought by the United Kingdom, by then the canal's leading user. The Suez Canal Company became an Anglo-French company in terms of both capital and governance.

Digging a canal in the middle of the desert across a distance of 160 kilometres was a colossal endeavour. Working conditions were quickly denounced as being close to slavery.

C. P.: To proceed with the construction in the middle of the desert, with no manpower available on site, the Viceroy of Egypt suggested that the Suez Canal Company use corvée labour, a traditional system in Egypt that mobilised peasants for a duration of one month for the maintenance of watercourses along the length of the Nile.

So the canal was indeed dug by free manpower working by hand under direct sunlight, in conditions of extreme hardship: tens of thousands of the 400,000 fellahs mobilised between 1859 and 1862 are thought to have died. Nasser would later mention 120,000 deaths, but there are no accurate archives to support this.

Yet criticism did not come from Egyptian society, for it was Britain that denounced the use of corvée, while the Ottoman Empire required Lesseps to stop construction. In the end, Napoleon III stepped in to arbitrate. Fellahs were replaced by foreign labourers from Greece, Italy, and Dalmatia, and unprecedented efforts at mechanisation were made, with investments to produce dredgers that could dig faster and deeper. The Suez project became a symbol of technical progress, and for that matter represents a crucial stage in the history of civil engineering. The canal was finally inaugurated in 1869 after ten years of construction, with lavish celebrations organised by the Viceroy of Egypt, who was proud of this showcase for Egyptian modernity.

Yet the honeymoon with Egyptian authorities would not last long...

C. P.: After the bankruptcy of 1875, which forced the Viceroy to sell his 44% share in the company, Egypt was subject in 1882 to military occupation by the British, who used the pretext of disturbances along this important commercial route to intervene. Egypt began a colonial period that would last until the 1930s, and at the same time lost all influence over the canal's management. All of the executive positions in the Suez Company were held by French engineers and foremen, and the Board of Directors was 100% European. The majority of skilled labourers were Greek and Italian, while the Egyptians held the lowest positions as unskilled workers.

Is this why the Suez Canal Company was criticised for being a state within a state?

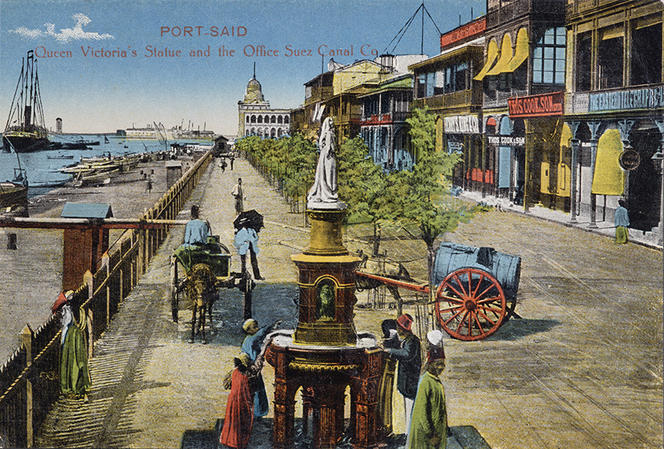

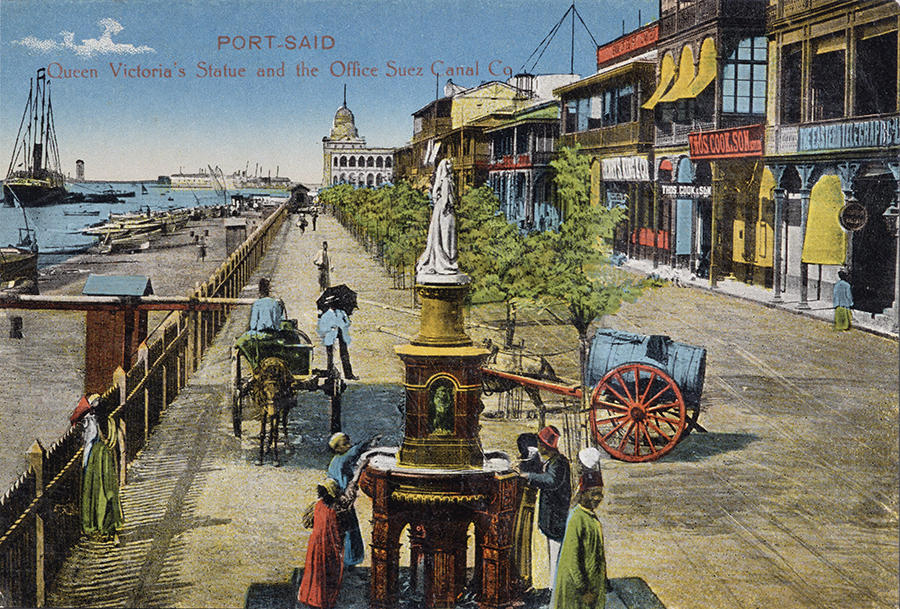

C. P.: Yes, but also because it was a kind of mini-society alongside Egyptian society. The company, which employed thousands of people, created two cities from scratch, Ismailia — where its administration was based — and Port Said on the Mediterranean, while the small fishing village of Suez became a leading Red Sea port. The architecture and lifestyle in all three were European. The firm had a highly paternalistic policy, subsidising schools reserved for French staff and those for Egyptians, as well as bringing missionaries for the Greek and Italian labourers.

Although accounts from the period speak depict a multicultural melting pot and gentle lifestyle, historians are dubious, for while these cities were certainly cosmopolitan, they were also very compartmentalised socially and geographically. In both Port Said and Ismailia, Arab and European neighbourhoods were separated, and in Port Said the company’s executives and workers were allocated different beaches.

When did relations begin to deteriorate between Egypt and the company?

C. P.: Friction set in during the early twentieth century between Egyptian nationalist movements, which were on the rise at the time, and the Suez Canal Company. But the true tipping point came in 1936, when the United Kingdom withdrew from the country's internal management. The company found itself alone before the Egyptian government, which asked for royalties for operating the canal, and demanded the firm's Egyptianisation in addition to the training of skilled Egyptian personnel, which French administration was reluctant to do. Tensions escalated, with rising discord between the company's foreign and local staff.

So President Nasser's announcement of the canal's nationalisation on 23 July 1956 did not come as a surprise for the Suez Canal Company?

C. P.: Nasser's announcement on the 4th anniversary of the monarchy's overthrow was not a complete surprise for people, even though it can be explained by an event that had nothing to do with the management of the canal. Nasser had just been refused financial assistance from the United States to build the Aswan High Dam, so it was primarily a way of expressing his displeasure and recapturing a certain amount of financial leeway. His decision was certainly brutal, although it is important to remember that the canal's concession was imminent, for according to the contract signed in 1856, Egypt would take over its operation in 1968.

By contrast, the Anglo-French military intervention a few months later was a dramatic turn of events!

C. P.: The French and the British did not want the canal's governance to fall to Egypt. They did everything they could from the 1930s onwards to show that the Egyptians were incapable of operating it properly, hence their reluctance to train local pilots to steer ships from one end of the channel to the other. They instead offered Egypt an international administration, in which the French and British were of course prominent. Nasser refused, which is why the military operation of 1956 was planned. The rest is history: according to a secret agreement, Israel invaded the Sinai Peninsula on 29 October, followed by France and the UK who bombarded the area surrounding the canal on 31 October, before parachuting in their troops, officially to maintain peace.

The so-called "Suez Crisis" was abruptly ended one week later under pressure from the United Nations, the US, and Russia, who did not want to upset Nasser and wished to ensure regional stability around the canal, which had become crucial for the transportation of oil. However, the damage inflicted on the Egyptians was considerable, with thousands of civilian and military deaths. The company's last French employees were hastily repatriated. From then on, the Egyptian Suez Canal Authority was in charge of operating the canal.

Was the canal an issue in the ensuing regional conflicts in 1967 and 1973?

C. P.: Absolutely not. It was not an issue in the Arab-Israeli War of 1967 (the Six-Day War) or 1973 (the Yom Kippur War), even though by virtue of its geographic position it became a de facto military border between the two belligerents. It was closed for eight years, and reopened definitively to navigation in 1975. Thanks to the Camp David Accords signed in 1978 between Egypt and Israel, the Suez Canal region is no longer an area of tension in the Middle East.

What role does the Suez Canal play in the Egyptian economy today?

C. P.: The canal is the country's second-largest source of currency after tourism, with revenues of 4.7 billion dollars in 2015. It is a booming maritime route that has taken full advantage of the growth of international commerce since the 2000s. In 2015, Egypt engaged in major construction work on the canal to improve the flow of traffic and increase profitability, especially through the creation of passing areas. Indeed, its permanence is at stake, for while it is a very popular maritime route that saves many ships from travelling around Africa via the Cape of Good Hope, the Suez Canal is not the only option for shipowners, who make their decisions based on the fluctuating fares set by the Egyptian authority.

For ships coming from the Pacific, or that are headed there from Europe, the Panama Canal is a true competitor; with the melting of Arctic sea ice, the Northern Sea Route via Siberia will prove to be an increasingly attractive option between Asia and Europe. Finally, the return to service of Syria and Iraq's oil pipelines could capture a share of hydrocarbon transportation, for which the canal is a favoured route.

- 1. Historian at the centre Roland Mousnier (CNRS / Sorbonne université).