You are here

The Nurturing Side of Ancient Arthropods

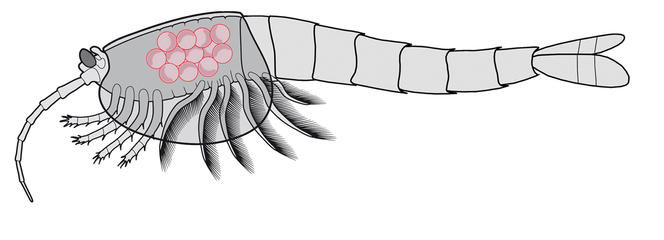

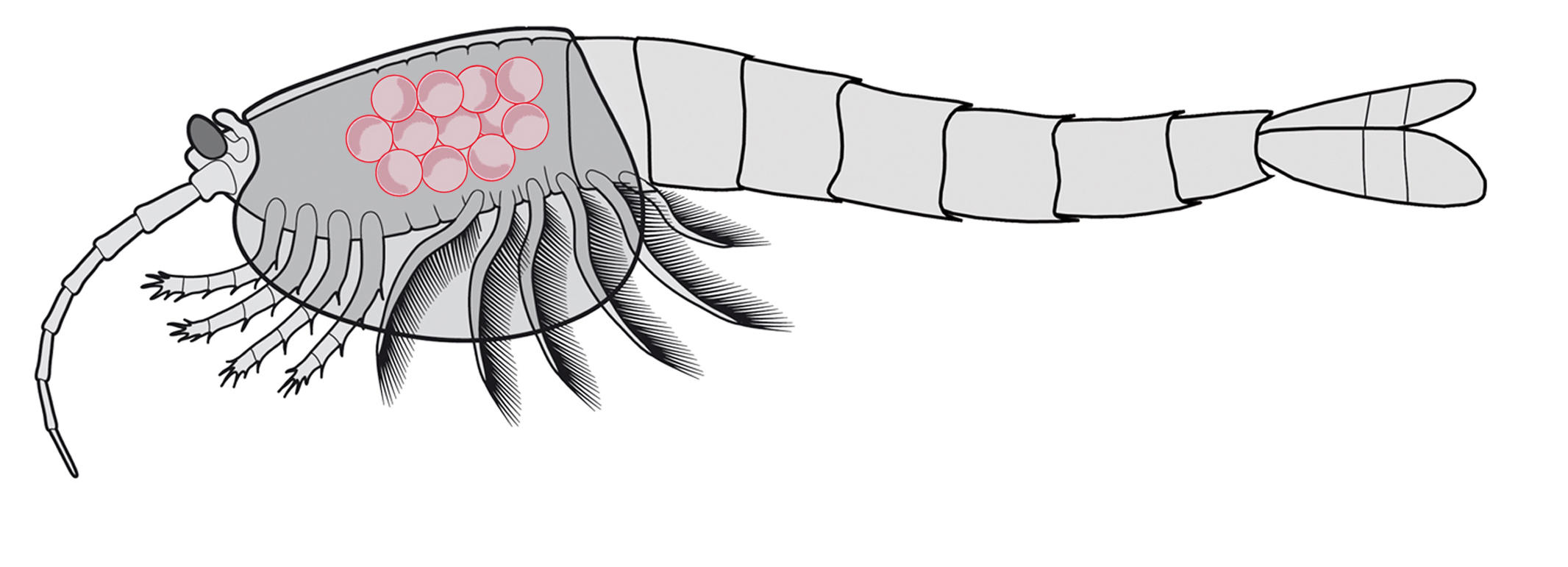

Many turn squeamish at the idea of arthropods and the creepy-crawlies like insects, arachnids, and crustaceans conjured up by this category of animals. Caring parents just don’t spring to mind. But as a French-Canadian research duo now shows, egg-carrying arthropods have a nurturing side that goes way back in time. Through analysis of fossils of Waptia fieldensis extracted from a 508 million-year-old Canadian site, the team has discovered that this species would store eggs—some with embryos—under its carapace to boost the next generation’s survival rates.1

A remarkable find

Until now, mystery has surrounded the reproductive habits of the first marine animals that appeared during the Cambrian, a period roughly between 540 million and 485 million years ago, when life on Earth underwent its quickest and widest diversification. Among these sea creatures was the now-extinct Waptia, characterized by a bivalved carapace covering its head and the front of its body, much like its lobster or crayfish descendants. Delving into the secrets of these lost species nonetheless remains possible thanks to sites like the Burgess Shale Formation, a rich deposit of Middle Cambrian fossils in the Canadian Rockies, known for its remarkable preservation of soft body parts.

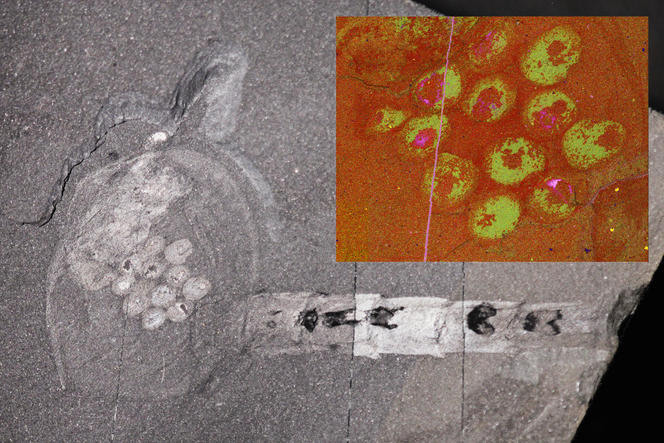

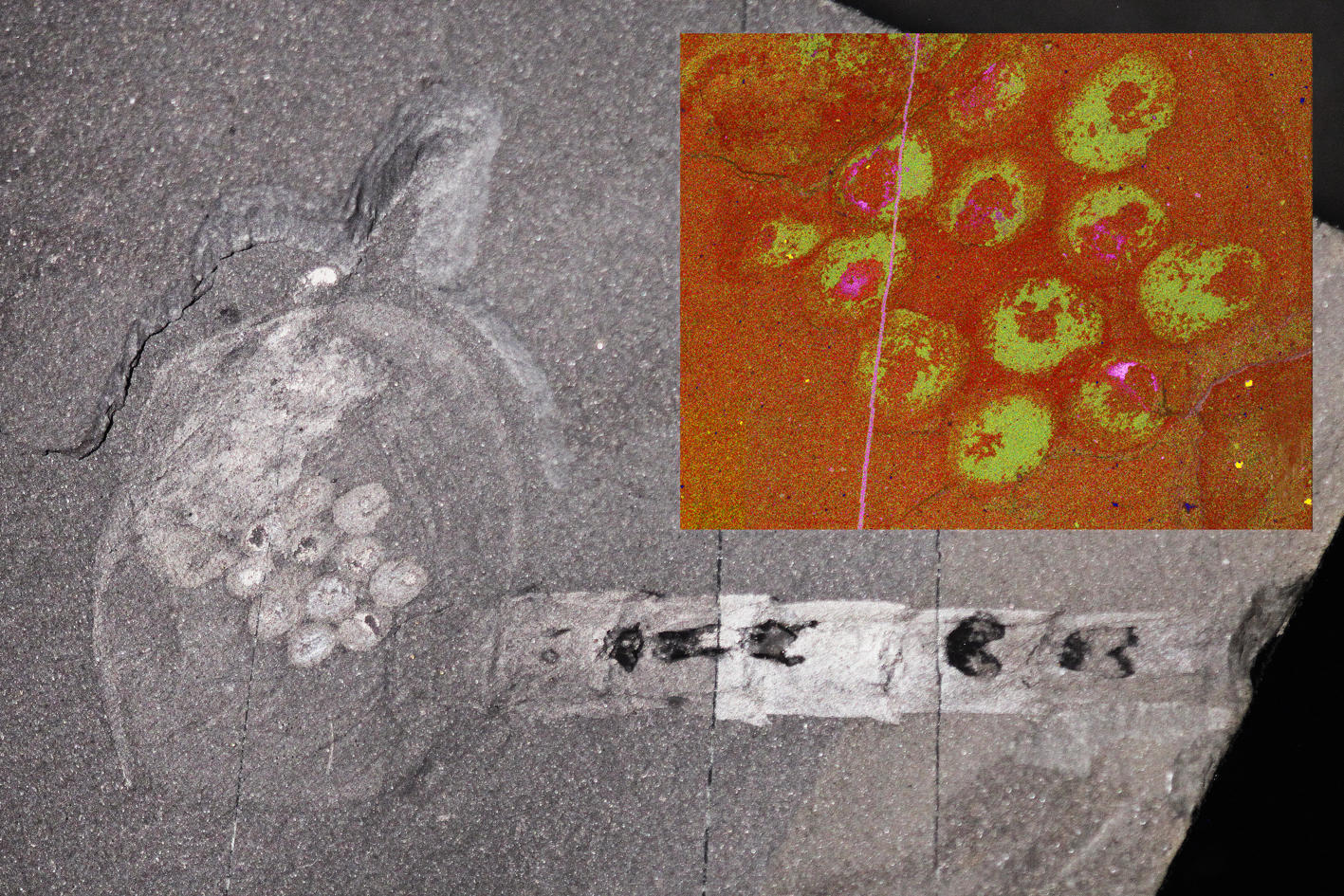

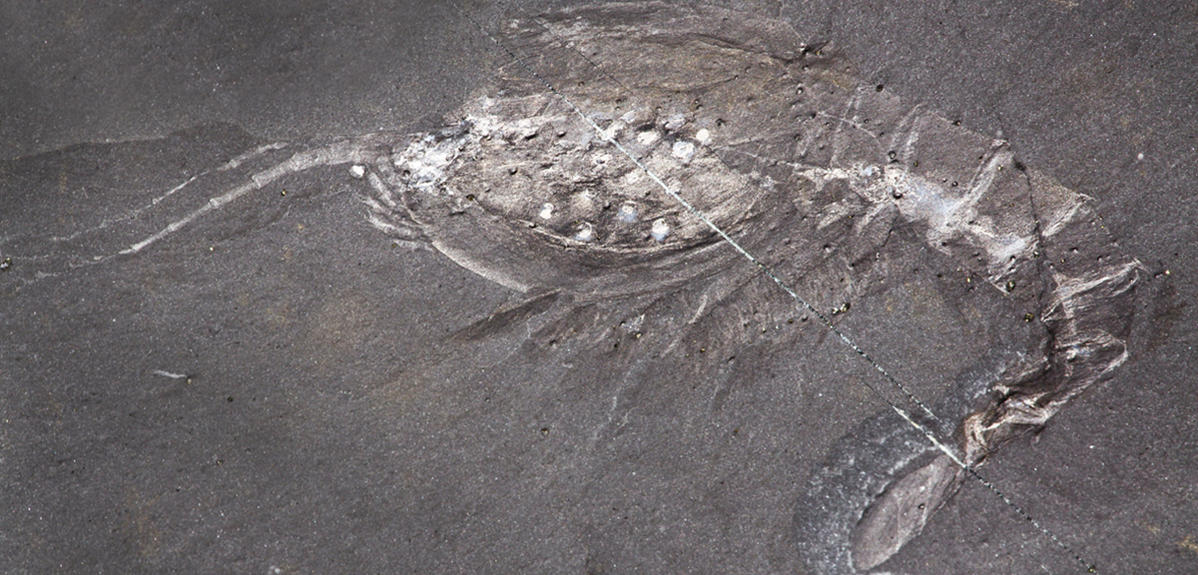

It was from their observations of Waptia specimens from the Burgess Shale Formation that paleontologists Jean Vannier of the LGTPE2 and Jean-Bernard Caron of the Royal Ontario Museum and the University of Toronto detected this arthropod’s striking parental behavior. Vannier notes that the Burgess fossils are “completely flat imprints” whose interpretation is made possible through “a combination of photography, electron microscopy, and elemental maps using energy-scanning spectroscopy to determine the fossils’ chemical composition.” In this way, the scientists singled out five specimens—out of a total of 979 examined—in which clusters of eggs were tucked under Waptia’s carapace. Significantly, some of these eggs contained developing offspring, thus emerging as the oldest preserved arthropod eggs with embryos to date.

According to the paleontologist pair, the carapace played a vital role in Waptia’s brooding ability. As well as sheltering the eggs from physical damage and predators, the carapace also offered a surface onto which eggs could possibly be fixed. In addition, ventilation in the space between the carapace and the body provided a well-oxygenated environment for the eggs.

Contrasting parental strategies

While Waptia’s shielding of its relatively large eggs and small clutches (a maximum of 24 eggs at once) stands out as one parental-care method, the two scientists note that it was not the only one to exist at the time. Another bivalved arthropod predating Waptia by seven million years, Kunmingella douvillei, discovered in China’s Chengjiang site, would carry a high number of small eggs lower on its body, fastened to its limbs. These contrasting parental strategies indicate a variety of techniques for safeguarding offspring in different species during the Cambrian. Indeed, for Vannier, the “Cambrian Explosion,” marked by the appearance of many animal species, was “accompanied by a rapid and amazing increase of behavioral complexity that affects all vital facets of animal life such as locomotion, feeding, and reproduction.”

Given the complexity of animals already present during the Cambrian, an inevitable “big question” pops up, that Vannier aims to tackle next in his research: “If we go back even further in time before the Cambrian, what might we find? What sort of animal life might we discover?”

Explore more

Author

As well as contributing to the CNRSNews, Fui Lee Luk is a freelance translator for various publishing houses and websites. She has a PhD in French literature (Paris III / University of Sydney).