You are here

A Jurassic Trail like No Other

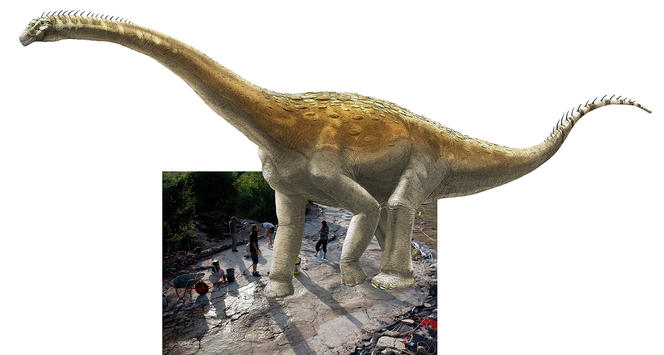

In 2009, when two members of the Oyonnax Naturalists’ Society went hunting for dinosaur remains in a meadow near the French village of Plagne in the Jura Mountains, their find would far exceed their expectations. “It was so big that we wondered if it really came from a dinosaur,”1 says Patrice Landry. He is referring to the first footprint from a set of tracks left by a sauropod. This dinosaur belongs to the suborder of long-necked, long-tailed specimens with four thick legs, like the diplodocus, which are among the most massive land-dwelling creatures of all time.

Nearly a decade after the Plagne discovery, geologists and paleontologists from the LGL,2 the LMV,3 and the Pterosaur Beach Museum have unearthed and probed many other prints along the same trail, found to stretch out over 155 meters to make up the world’s longest currently-known sauropod trackway.4 A colossal find that helps decipher the secrets locked up in the ground of the famed region which spawned the term “Jurassic.”

The 2009 discovery of the world’s largest dinosaur tracks on the Plagne limestone plateau stirred the excitement—and also anticipation—of dinosaur enthusiasts all over the planet. “After the amateur naturalists alerted us of their discovery, we came to evaluate the site,” recalls Jean-Michel Mazin, paleontologist and emeritus CNRS senior researcher formerly attached to the LGL. “Right away, we identified the distinctive marks of a sauropod with very large ovoid or rounded feet. Next, we started prospecting the plateau to see if it would be worth organizing an excavation campaign.”

Wise decision. Digs overseen by the LGL on the 3-hectare site between 2010 and 2012 uncovered a total of 110 prints that together make up the world’s longest set of sauropod tracks, longer than the previous record-holder, a 147-meter-long trackway in Galinha, Portugal.

Mazin emphasizes that the discovery of prints on this scale is “a matter of conservation and above all, chance. Any animal or human walking around in nature leaves behind prints but wind or rain destroys a majority of them. But sometimes, conditions come together for prints to dry and stay protected for millions of years.”

This was the fortunate case of the Plagne tracks. Study of the site’s sedimentary succession (chronology of rock layers) as well as rare ammonite fossils allowed the team to trace the prints’ formation back 150 or so million years ago during the Tithonian, the last age in the Late Jurassic epoch—a time when the Jura looked very different from the alpine mountain chain we know today. “It was a marine environment with a large inland sea surrounded by land surfaces including chains of sandy islets,” says geoscientist Nicolas Olivier of the LMV. He adds that the land surfaces were probably “fairly substantial as they held enough vegetation to feed big dinosaurs that had huge appetites.”

Not only was the Jurassic sea shallow—“several meters deep at the most,” he says—but climatic changes also imposed periodic low-sea cycles when swampy land bridges linked up the islands, allowing animals to expand their territory or even migrate. This was the scenario when one particular sauropod crossed the tidal flat that became the Plagne site and left its prints in the mud. “After the prints dried, the sea returned and filled them with sediment that hardened into rock and kept them intact against erosion agents until today,” Olivier explains.

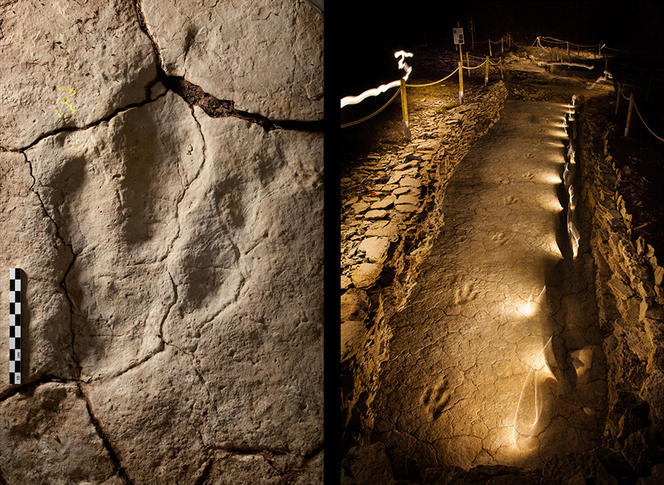

In order to scrutinize the tracks carefully, the researchers combined field study with silicone-rubber casting as well as a range of imaging technologies such as aerial photographic mapping using a helicopter drone, and laserometry for 3D scans of the excavated area. The tracks consist of both arc-shaped handprints with five circular finger marks, and footprints with five elliptical toe marks. While the sauropod's foot length ranged between 94 and 103 centimeters, the print length went up to 3 meters when including the ring of mud formed by the heavy animal’s stomping.

Using biometric analysis of the prints, the team established that the sauropod was at least 35 meters long and weighed between 35 and 40 tons. It also had an average stride length of 2.8 meters as well as a travel speed of roughly 4 km/hour. Noting the similarity of the specimen’s features to the existing ichnogenus5 Brontopodus (literally, “thunderfoot”), the team has attributed the new ichnospecies of Brontopodus plagnensis to the Plagne sauropod.

While the scientists focused their efforts on exploring the single trail left by the “Thunderfoot from Plagne,” they also excavated two nearby trackways, this time left by theropods (a dinosaur suborder characterized by three-toed limbs), namely a 38-meter-long trail left by a 3-meter-high, 9-meter-long carnivore. A discovery that suggests the region had a very rich fauna during the Jurassic.

Pending decisions by Plagne’s local authorities on how to protect this precious site and present it to the public, the tracks have been reburied to shield them from the elements. “The Jura climate is particularly harsh with snow, rain and storms,” points out Mazin. But the researchers suspect many more dinosaur traces are still sealed up in these mountains which could yield more discoveries in the future. “Only a tiny section of the site was excavated,” concludes Olivier. “Further findings would help improve our knowledge about the diversity of organisms in the area which would help us better understand the ecosystem at the time.”

- 1. In the documentary: “Sur la piste des dinosaures.” Dir. Marie Mora Chevais, CNRS Images, 2009: https://lejournal.cnrs.fr/videos/sur-la-piste-des-dinosaures.

- 2. Laboratoire de Géologie de Lyon (CNRS / ENS de Lyon / Université Claude Bernard).

- 3. Laboratoire Magmas et Volcans (CNRS / Université Clermont Auvergne / Université Jean Monnet / IRD).

- 4. J.M. Mazin, P. Hantzpergue & N. Olivier, “The dinosaur tracksite of Plagne (early Tithonian, Late Jurassic; Jura Mountains, France): The longest known sauropod trackway,” Geobios, August 2017. 50(4): 279-301.

- 5. Ichno-: a taxon defined from marks like tracks rather than anatomical remains.

Explore more

Author

As well as contributing to the CNRSNews, Fui Lee Luk is a freelance translator for various publishing houses and websites. She has a PhD in French literature (Paris III / University of Sydney).