You are here

An Anthropological Approach to Biomimicry

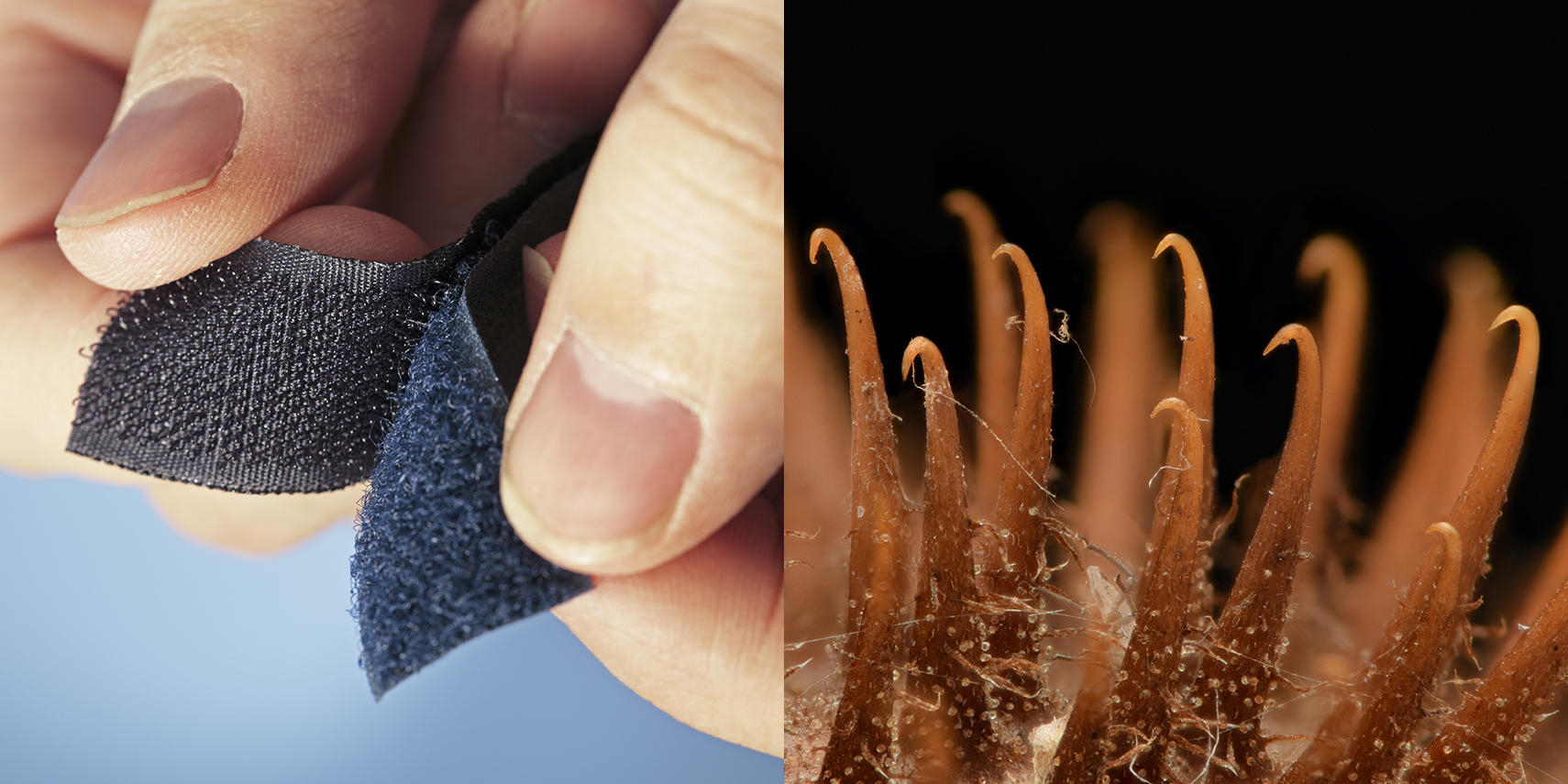

We know the story of Velcro, whose tiny hooks were inspired by the burdock plant, or that of wetsuits, which imitate the roughness of a shark’s skin. This approach towards technological and engineering innovation is known as biomimicry, which draws inspiration from forms, materials, etc. taken from the living world. But what are the origins of this concept, and what else does it include?

Lauren Kamili:1 The term was coined in 1969 by biophysicist Otto Schmitt, but it flourished in the late 1990s, when social and ecological crises, as well as the exhaustion of natural resources, prompted research into less destructive societal models. A turning point came with the publication of Biomimicry: Innovation Inspired by Nature in 1997, by the American biologist Janine Benyus, in which she defines biomimicry as “the conscious imitation of life’s genius. Innovation inspired by nature.” For Benyus and contemporary practitioners, the living world is the result of 3.8 billion years of research and development. She also discusses what she calls “life’s principles”: using solar energy, not producing waste, recycling everything...

Perig Pitrou:2 Ecology has not always been at the forefront when it comes to drawing ideas from nature. You can have a “bio-inspired” approach that observes natural systems in order to produce objects that, in the end, do not necessarily protect the environment. For example, technologies that imitate photosynthesis can be environmentally damaging if they use harmful chemical components. In contrast to this bio-inspiration, biomimicry is sometimes presented as a more complete project, one in which the objects produced by humans can be reintegrated into natural cycles with no pollution.

The field is especially associated with the natural sciences and technological innovation. As anthropologists, how do you approach the question of biomimicry?

P.P.: The Humanities and social sciences have engaged with it only in recent years, hence the idea for our interdisciplinary conference on the subject. I am in charge of a research team called “Anthropology of life”, whose aim is to explore variations in conceptions of life and living beings across space and time, by examining the technological activities and collective projects developed by human societies. Biomimicry is an interesting practice for addressing these two technological and social aspects. Imitation is not the immediate reproduction of nature, as it entails a certain number of stages and operations, including observations, measurements, drawings (...), and potentially the construction of objects. We believe that it is relevant to observe the entire operational chain that is behind it. Similarly, nature should not be imagined as a professor giving lessons, for it is humans that choose and distinguish the elements that they want to imitate.

The two primary criteria used by humans in this form of thought are effectiveness (such as imitating the shape of a kingfisher’s beak to improve the aerodynamics of a high-speed train), and symbolic value (such as imitating the movements of an animal during an initiation ceremony in order to incorporate its qualities). We therefore recommend adopting biomimicry in the broader sense of the word, by including phenomena from highly diverse societies within this category. We must not forget that imitation of nature is ancient, and that it should not be limited to Western societies and technological progress. That is one of the lessons of ethnology.

What illustration can you give us based on your experience as an ethnologist?

P.P.: Humans do more than imitate living beings: they can also imitate ecological systems, as I observed during fieldwork in the Mexican state of Oaxaca, where some Amerindian populations perform miniaturisation rituals. The peasants distribute—on scaled-down versions of landscapes or fields—corn as well as water evoking rain. These systems can be interpreted as a manifestation of the human capacity to imitate—up to and including large-scale cycles of nature—as well as a desire to be the cause that allows living beings to grow. The imitation of nature has a universal dimension among humans, who also make choices based on their specific projects.

Concretely, how do you identify a process of imitating nature?

P.P.: Observations and experimentation must be brought into relation with one another. Anthropology can base itself on ethnographic explorations. This can happen through the documentation available on locations where it is practiced. It can be done in Amazonia, where Philippe Descola showed how the Achuar cultivate their gardens using models from the forests. Explorations can also be conducted in laboratories. Lauren Kamili is part of a new generation of researchers that works in an interdisciplinary framework and needs to be familiar with the vocabulary of science, just as others learn vernacular languages in order to successfully carry through their research.

L.K.: As part of my thesis I am going to explore the Laboratoire de Chimie Bio-Inspirée et d’Innovations Ecologiques,ChimEco (CNRS / Université de Montpellier).3 directed by Claude Grison. She studies how plants store and accumulate heavy metals, in an effort to create depollution protocols for contaminated mining sites. I will observe the approach taken by researchers as well as potential ethical questions, for example when potentially invasive plants are used.

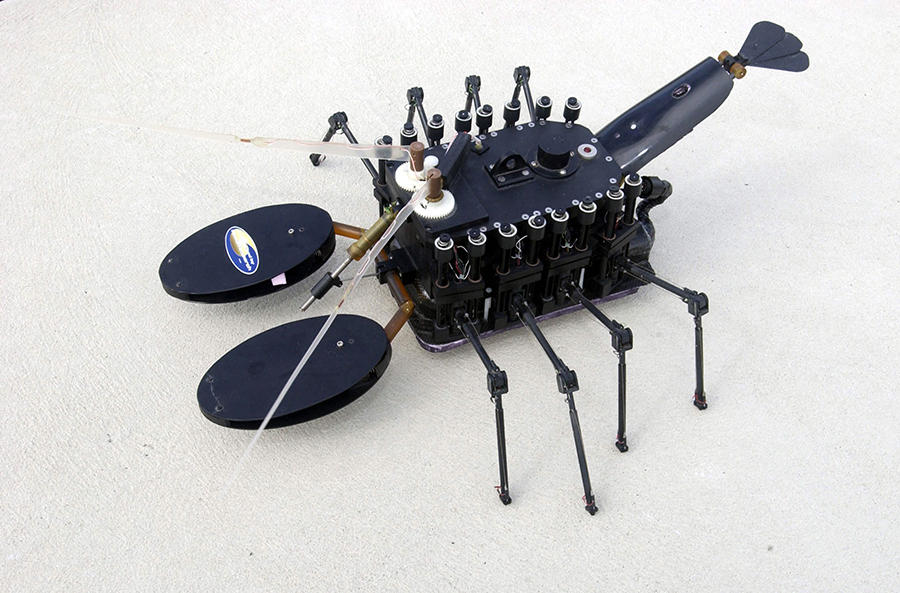

I am interested in how cultural and social values, which are sometimes highly diverse, influence contemporary biomimicry’s framing of nature. While the rest of the community does not always approve of it, the military domain represents a good example of biomimicry, one that is based on intentions that are not very peaceful. Among our speakers, Elizabeth Johnson from Durham University (UK) has devoted a chapter of her thesis to American laboratories that study how lobsters move from water to land, in order to design robots that allow troops to disembark more easily while clearing the area of mines.

What role does biomimicry play in Western capitalist societies?

P.P.: To properly understand the complexity of biomimicry, it is important to observe the actors and their projects in their diversity, in both the modern Western world and more traditional societies. Some projects are explicitly conducted to gain profits, while other perspectives focus more on citizen science. Once again we should pay attention to the variety of models used by collectives that lay claim to a biomimetic approach. Fundamental conceptions of nature are what must be parsed out in the background.

When observing life, humans can focus on peaceful relations, such as exchange or symbiosis, although more antagonistic relations such as predation can also sometimes be emphasised. As a researcher working in the field of the anthropology of life, I am interested in the conceptions of life that underpin the collective technologies and projects established by human groups with nature as a model. Based on these cultural choices, each society does more than simply select certain aspects of life to produce artefacts: it finds inspiration for building a social order, including by distancing itself from the natural order.

How is the biomimicry community structured and organised in France?

L.K.: A great diversity of actors lay claim to biomimicry, including companies, public laboratories, and citizens’ associations, resulting in a number of communities with their own sets of values. Many actors have come together around the Centre Européen d’Excellence en Biomimétisme (CEEBIOS) in Senlis (Paris region), an organisation that has, for instance, worked with the Association Française de Normalisation (AFNOR) to establish ISO standards for biomimicry. The cooperative company Terre vivante is an alternative actor that belongs to this network, but upholds different values.

P.P.: Collectives vary a great deal depending on the socioeconomic project they seek to implement. The idea of reconnecting humans with the natural environment also means reappropriating the knowledge and know-how related to life. Alongside projects that adopt an engineering approach as a model are other biomimicry approaches connected to do-it-yourself biology, which invite people to observe and experiment with living beings. The scientific community includes chemists, biologists, physicists, roboticists... The CNRS launched a call for projects on the topic at the beginning of the year, from which diverse subjects emerged, such as studying the colouring of sea urchins or the production of mechanical parts inspired by bones. Each laboratory follows its version of biomimicry, but the good news is that the CNRS is enabling them to coalesce. In the long term scientists may even develop methodologies for guiding interdisciplinary research in this field.

_____________________________________________________

What exactly is biomorphism?

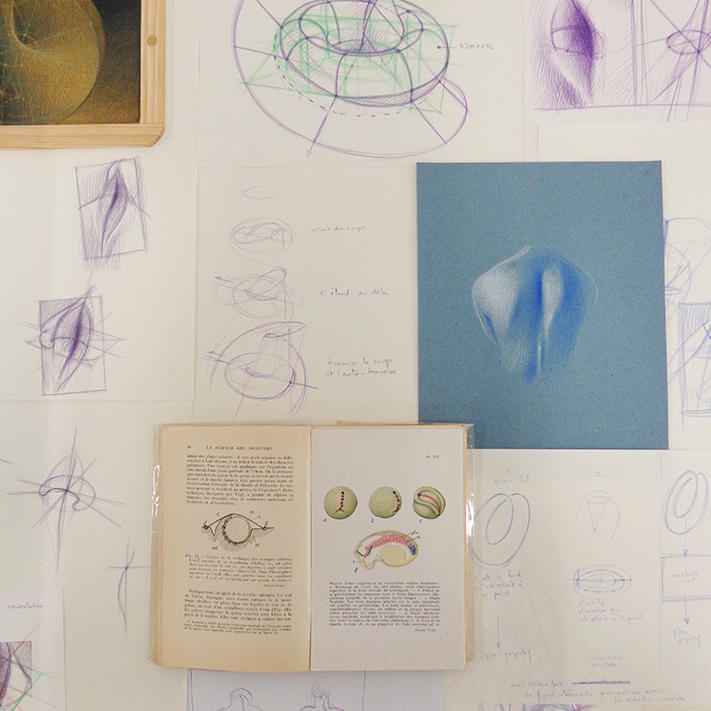

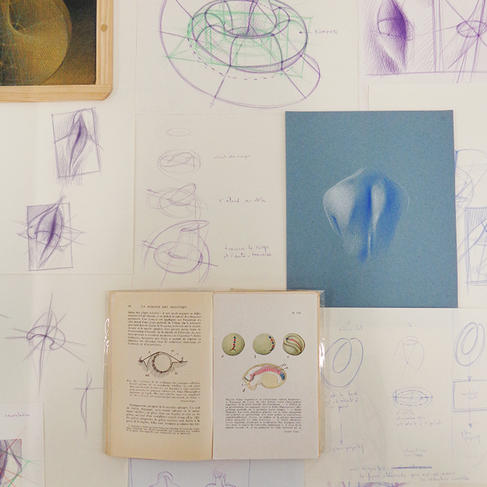

Life has always been a source of inspiration for artists as well. Those belonging to the collective “Biomorphism: Sensible and Conceptual Approaches to Forms from the Living World,”4 have chosen not to focus on “realistic” images that feature the familiar silhouette of the forms of life that we come across on a daily basis. They instead use the multiplicity of digressions (change of scale, abstraction, poetic symbolisation, morphological studies, etc.) to reveal the more complex and hidden aspects of life. The central consideration is to construct and convey collective and transdisciplinary representations of life, in all its specificity, commensurate with the challenges relating to the cohabitation of all living beings in the Earth ecosystem.

Learn more

The meetings of the journal Techniques & Culture on the topic of “Biomimicry, imitation of the living world and modelling of life,” organised by Perig Pitrou, Lauren Kamili, and Fabien Provost,5 was held on 24-25 September in Marseille.

- 1. Lauren Kamili is a PhD student at the School of Advanced Studies in the Social Sciences (EHESS). Her doctoral thesis is funded by the Agence de l’Environnement et de la Maîtrise de l’Énergie (ADEME).

- 2. Perig Pitrou is a senior researcher at the Laboratoire d’anthropologie sociale (CNRS / Collège de France / EHESS), where he heads the “Anthropology of life” team. He was awarded the 2016 CNRS bronze medal.

- 3. ChimEco (CNRS / Université de Montpellier).

- 4. Programme AMU / CNRS / Fondation Carasso.

- 5. Researcher at the Laboratory of Ethnology and Comparative Sociology (LESC – CNRS / Université Paris Nanterre).

Explore more

Author

A graduate from the School of Journalism in Lille, Martin Koppe has worked for a number of publications including Dossiers d’archéologie, Science et Vie Junior and La Recherche, as well the website Maxisciences.com. He also holds degrees in art history, archaeometry, and epistemology.