You are here

Barbara Cassin: 2018 CNRS Gold Medal

Presenting Barbara Cassin simply as a Hellenist, philologist, philosopher and CNRS senior researcher emeritus, somehow doesn’t seem an adequate description for this dynamic intellectual. A year ago, Cassin had taken on the role of curator of the exhibition ‘Après Babel, traduire’ (‘Translating after Babel’) for the Museum of European and Mediterranean Civilisations (MuCEM) in Marseille, while at the same time working on a monumental dictionary of the three monotheistic religions. Her research has taken her from Homer to Heidegger, via Leibniz and psychoanalysis, not to mention the many cultural exchange programs to which she has contributed. When we met Cassin at home in 2017, in her winter garden in the heart of Paris’s Latin Quarter, we were wondering how to summarize her extensive bibliography, her work and her many commitments. “It’s quite simple,” she says. “I have always been concerned with what words can do.”

As a child, Barbara, who was born in the Paris suburb of Boulogne-Billancourt two years after the end of the Second World War, discovered the power of words well before she reached the age of reason. Or, to be more precise, Barbara, Laure or Sylvie, since her parents had given her three first names, never suspecting that she would play around with them, choosing one name or another depending on her mood or desires. Until, as a teenager, she settled on Barbara, so closely related to the word ‘barbarian’ used by the Ancient Greeks to refer to those who didn’t speak their language. For by now, her mind was made up: she was going to learn other languages, an essential step towards seeing the world from many different viewpoints.

At high school, it was thanks to her teacher of Ancient Greek that she first fell in love with the language and its great philosophical writings. And yet she was also attracted by other avenues, such as theatre, painting, poetry or founding a family. So why did she choose philosophy? “Because I thought it was the most difficult path,” explains Cassin, who is something of a workaholic.

Right from her early days as a student, the ‘Cassin method’ began to take shape. It is through language and discourse that we must address philosophy and its fundamental questions: what can we know about existence and Nature? To obtain her master’s degree in philosophy at the Sorbonne in 1968, she decided to tackle the great metaphysical debates that were so popular in the late seventeenth century, a period shaken by both the scientific revolution and the fresh new philosophical thinking advocated by Descartes. However, Cassin chose to do this through an exchange of letters between the philosopher and mathematician Leibniz and an opponent of Cartesian theories, the Belgian theologian Antoine Arnauld: she was less interested in the relevance of the theses defended by the two men than in the logical and rhetorical devices they used to make their case and try to convince the other party. For Cassin, such discourses are more important than the search for truth, for it is they that forge societies. In a manner of speaking, making sense of them consists in becoming less naive about our belief in philosophy. From then on, she was never to give up her desire to immerse herself in the study of language. She borrowed a term from Novalis (also used by Dubuffet) to describe this activity: ‘logology.’

This was an ambitious program, and her love of words was to cause the young philosopher quite a few problems. Feeling hemmed in by the compartmentalization of disciplines at the university, she cheerfully married literature with history and dialectics. However, her inability to separate these different types of discourse didn’t make her task any easier: her six attempts to pass the agrégation exam all failed. “On my third attempt, I expressed, in a somewhat personal way, the relationship between the God of Aristotle and that of Leibniz as being that of a shift from God the Prime Motor to God the promoter, and I was rather pleased with that," Cassin laughs. The examiner clearly didn’t share her delight at her clever turn of phrase, and marked it 2/20.

Meeting with Heidegger

Even though she failed to embark on a brilliant academic career, during her student years Cassin “worked as she had never done before,” accumulating knowledge and decisive encounters. Through her professors Jean Beaufret and Michel Deguy, she had the opportunity to take part in one of the seminars of Martin Heidegger, the German philosopher whose thinking on Being and on language had considerable influence in the second half of the 20th century in every intellectual circle. At that time, in the late 1960s, the controversies over Heidegger’s Nazi past were yet to erupt. Although Cassin, who is Jewish, was aware of this, she didn’t see it as an obstacle. She shares the point of view of Hannah Arendt, of whom she was one of the first translators, who considered that philosophers have always had a soft spot for tyrants: the same person can be both a great thinker and an ordinary Nazi: philosophy just has to accept this.

Remaining far from the compartmentalized world of the Sorbonne also enabled Cassin to turn towards the CAPES (a secondary school teaching diploma) and to a wide range of teaching methods, “which was an extremely valuable experience, since it forces you to be inventive all the time.” For instance, she would ask her bright but slightly arrogant math students to think about the concept of ‘number.’ She explained to her students at ENA (an élite school that trains future senior public servants) that working in groups with individual assessment (which would seem contradictory and was seen as an aberration) was exactly the best way to train future diplomats.

Regardless of the setting in which she taught, Cassin always attempted to get her students to understand the power of words. The experience that left its mark on her most lastingly was undoubtedly the two years she spent with psychotic adolescents at the Étienne-Marcel hospital in Paris, where the famous paediatrician and psychoanalyst Françoise Dolto practised. To overcome the considerable language difficulties they suffered from, Cassin got them to write and produce a genuine newspaper that they then sold in the street. In another exercise, she wrote Greek words that they couldn’t understand on the board, to make them aware that there were also words that they did understand since they had a mother tongue. From then on, Cassin began to include psychoanalysis in her already very wide-ranging research portfolio. This gave her the opportunity to publish several books about the psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan, including one co-written with Alain Badiou,1 who, although mainly known for his political commitments, has also written extensively about logical philosophy.

However, there was no question of her giving up philosophy, indeed quite the opposite. In 1984, she was taken on by the CNRS at the Centre Léon-Robin,2 a research center on ancient philosophy. And ten years later, she finally obtained proper recognition from the university: she brilliantly defended her doctoral thesis, which was published under the title ‘L’Effet Sophistique’ (the Sophistic Effect’).3 Prospering in the pre-Socratic Greek world, those who would later be known as sophists professed to teach the art of convincing a judge, an opponent, or an assembly. Plato, in his Gorgias dialogue, and then Aristotle rapidly denounced the sometimes spurious reasoning that these language professionals used to promote their eloquence. This view has prevailed to this day: a sophism is defined as purely verbal reasoning, without solidity and based on fallacious logic. Everyone knows the syllogism which states that a cheap horse is expensive, since cheap horses are rare and everything that is rare is expensive.

In her thesis, Cassin goes back to the original sources, in other words to the works of the sophists themselves, especially those of Gorgias. She retranslated his Encomium of Helen, in which he defends Helen’s innocence, even though she had caused the Trojan War. Cassin maintains that it is through his discourse and its logical power that Gorgias manages to turn the situation around, achieving a performance in the literal meaning of the term. It is this logical performance that she then seeks out in the Socratic dialogues. Although Plato mocks the sophists, Cassin points out how they lead us to understand that philosophical truths, even those considered to be the most fundamental ones, are first and foremost an effect of discourse. And yet, by considering from the outset sophistics as something to be rejected and avoided at all costs, philosophy has deprived itself of what Cassin calls “the measure of truth”. “Philosophy is an all-powerful tradition, but we can only successfully understand how it works if we place ourselves slightly outside it, in a kind of deterritorialization. That is what the Sophistic Effect is.”

For Cassin, there is no room for doubt: words have the power to make things happen. In this respect, they also have a political dimension. She was able to demonstrate this when Nelson Mandela became President of South Africa, by contributing, through an international agreement with the CNRS, to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission set up in 1995 as part of the end of apartheid and the democratic transition. “As philosophers, Barbara and I thought long and hard about reconciliation and, in our report, we outlined how the pacification of the nation could be achieved through the use of rhetoric," says Philippe-Joseph Salazar, Dean of the University of Cape Town’s Faculty of Humanities. What were seen in Europe as legal debates were in fact political debates, and they were to help shape the ethical form the new State would take.” A fine demonstration of how words can help build a nation. The report, which Salazar has no hesitation in putting on a par with Rousseau’s Social Contract, has become an indispensable reference in all the countries, such as Rwanda, Tunisia, Ivory Coast and Peru, that have set up this type of commission, Although, as Salazar regretfully points out, adapting it to each country and to different languages has not always been easy.

The ‘Untranslatables’ project

This is a problem that Cassin is well aware of. Pondering the meaning of words when they migrate from one language to another has long been a concern of hers. For the past twenty years, she has been wondering what shape European philosophy could take, in an age when globalized English, or ‘Globish,’ is used all over the world. A first response came in 2004, in the form of an object that is unparalleled in the history of philosophy, or possibly even of publishing: the ‘Vocabulary of European Philosophies,’ better known by its subtitle, the ‘Dictionary of Untranslatables.’ This monumental work looks at 1500 words of philosophical language and at the difficulty of translating them into some fifteen other languages. “When a word is translated, the meaning is no longer quite the same nor is it completely different,” Cassin says. “There is always more than one good translation possible. Indeed, even the word ‘translate’ has several meanings!” The dictionary, in which she managed to involve 150 researchers and translators from around the world, does not provide the ‘right’ translation. On the contrary, it shows inconsistencies and differences: ‘untranslatables’ are “not what we can’t translate, but rather what we (don’t) translate over and over again.”

Cassin claims this as a political act. Similarly, she conceived the MuCEM exhibition ‘Après Babel, traduire’ as a demonstration (in the literal sense of the term) of expertise in diversity: here, there is no need for semiology, since evidence is provided by the exhibits. This recognition of diversity is also a feminist statement for Cassin, who considers that notions such as ‘universal’ and ‘Truth with a capital T’ are the result of a male relationship with philosophy. In fact, this is another issue that fuels her discussions with Badiou, with whom she is working on a book on how men and women relate to philosophy.

Before that, there will probably be the publication of a new Dictionary of Untranslatables, this time of the three monotheistic religions, since the three great sacred texts, the Torah, the Bible and the Koran, also have much to tell us about our relationship with languages and words. “First we’ll have to find funding, since this kind of publication is extremely expensive,” Cassin sighs. “You need a lot of perseverance to get scholarly works of this kind accepted by funding systems," adds Salazar, who emphasizes the marginalization of language experts in Europe, when conferences on rhetorics in the US bring together thousands of participants.

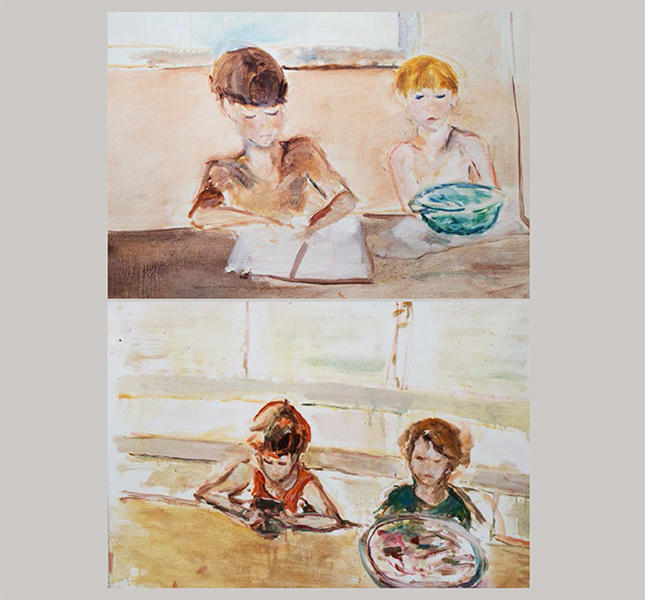

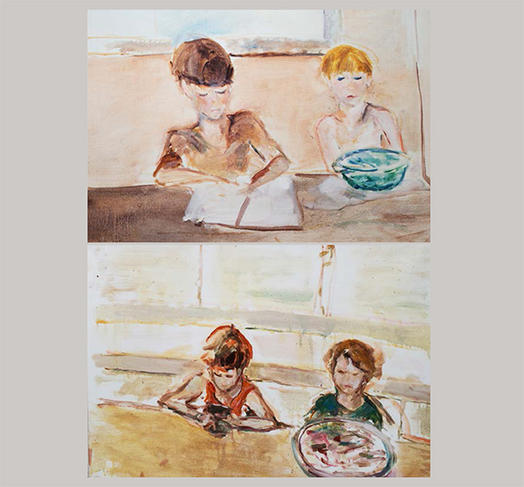

Cassin’s big worry is running out of time. A Chair at the Sorbonne? She turned it down, for fear that she wouldn’t be able to continue her work all over the world. Political commitments? They take up too much time. Likewise for the political manoeuvering and networking that can help you to advance your career. “Everything that’s happened to me at the CNRS, right up to becoming the director of the Centre Léon-Robin, was simply down to a great deal of luck. I never really wanted it, let alone asked for it,” she insists. She wants to use her time to carve out her own path, where saying something really does mean doing something. At the risk, she admits, of repeating herself, especially since she is currently working on several books at the same time, not to mention articles, contributions, exhibitions and so on. “So I write in the same way as I paint,” Cassin admits, “hoping to be surprised.” She points to two of her paintings, hanging one above the other: same format, same hues, and almost the same figures. And yet the two pictures (see above) are over twenty years apart: one shows her two sons aged 8 and 3, and the other one her two grandsons at the same age. They are almost identical, and yet with tiny differences. “Writing about language should have the same effect as painting,” she observes. “You should surprise yourself and change your perspective on things. You need to rinse out your eyes. Literally.”