You are here

Blade Runner: Can We Replicate Humans?

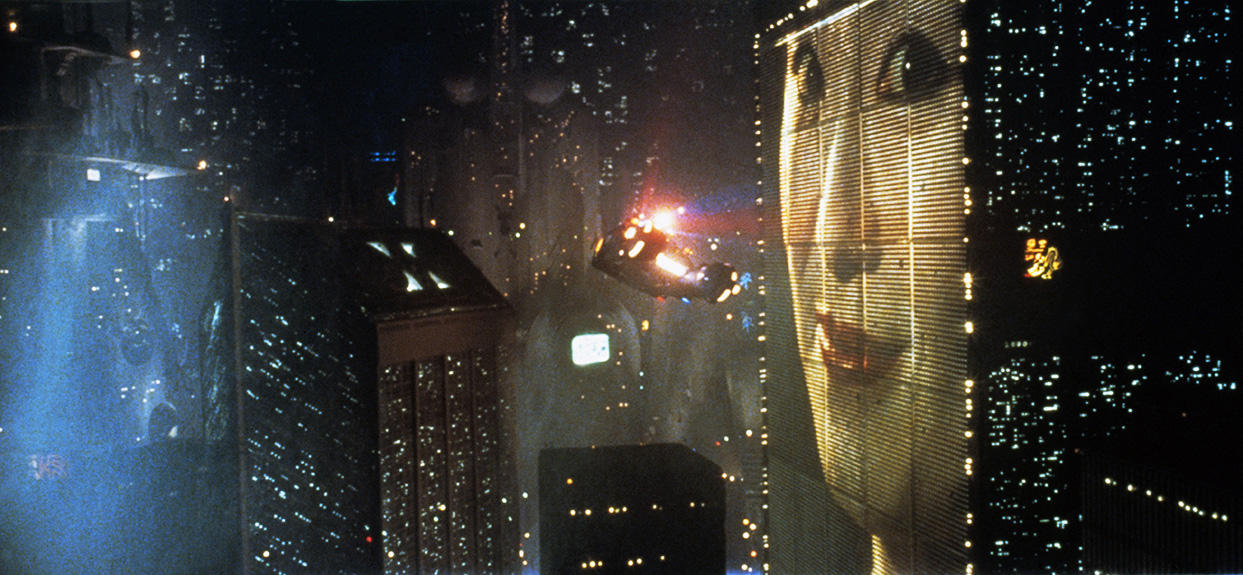

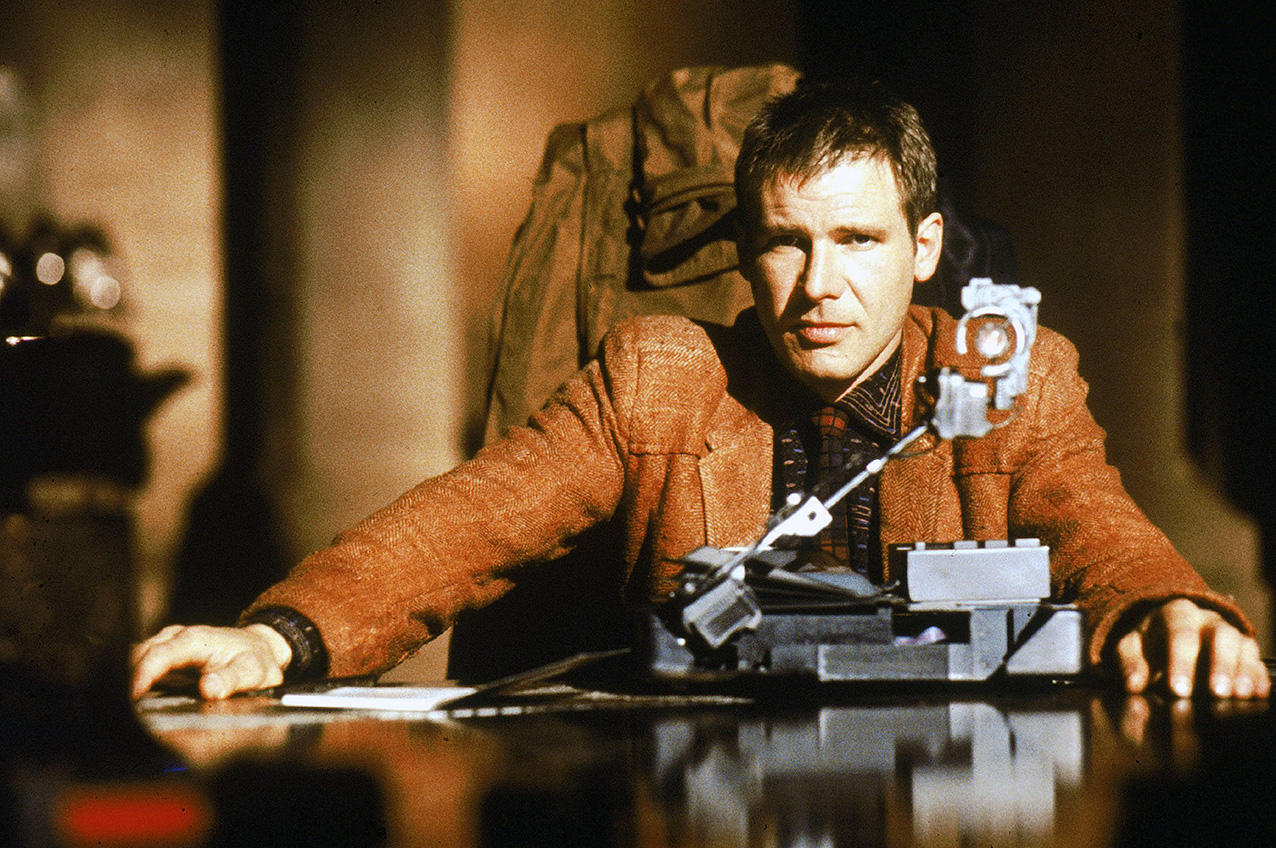

Blade Runner (1982),1 directed by Ridley Scott, is now such a cult classic that it’s easy to forget that the film was coolly received by the public and panned by the critics when it was released in 1982. Fortunately, Denis Villeneuve’s new version, Blade Runner 2049, is neither a remake nor a watered-down sequel, but first and foremost a tribute to a work that has influenced international cinema as well as our vision of the world. In the original, Harrison Ford, in sharp contrast to his role as Han Solo in the Star Wars movies of the same era, portrayed Rick Deckard, a cynical detective in the style of a 1940s crime thriller, a none too fine example of humanity who turns out to be considerably shadier than the “replicants”—the androids, powerful and dangerous rebels, that he is assigned to eliminate. Blade Runner invented the esthetic of 20th-century terrestrial science fiction. Its specific texture and style, a blend of neo-noir and special effects set in a baroque and futuristic cityscape of skyscrapers, flying cars and misshapen creatures, has been imitated countless times. This society of the future, very much alive but gloomy and ravaged, due to declining population, violence and poverty, is our own. Preceding the post-apocalyptic world featured in so many fictional depictions of the 21st century, Blade Runner symbolized the pre-apocalypse and humanity under threat.

Descartes and Deckard

Setting the action 30 years after that of the original, Blade Runner 2049 reminds us, if we need reminding, that the first Blade Runner took place in 2019, in other words in the present day or immediate future. The 2019 of Blade Runner is our time, and the issue that it raises concerns us: that of being human, or more precisely the definition and limits of it. The pre-apocalyptic style brings forth a metaphysical theme in the specific form of a skeptical question: how do I know that I am dealing with a human? What are the criteria that make someone human?

The existence of android robots that are much superior to us both physically and intellectually, like the Nexus 6 model in the film, raises questions about humanity. Other more recent films have addressed the same theme, including A.I., I Robot, Ex Machina and the science-fiction series Real Humans and Westworld.

But Blade Runner was the first to convey such philosophical skepticism in cinema—doubt as it was expressed (before being refuted) in the writings of Descartes and Hume. Deckard practically assumes the name of the former, who is also referenced by the persona of Pris:2 “I think, Sebastian, therefore I am.” Some of us will recall that Hume is the name of a key figure in the series Lost, which is also based on the skeptical questioning of the reality in which its characters live.

Scepticism and tragedy

Blade Runner unfolds and is perceived as “a moving image of skepticism,” to borrow an expression from the philosopher Stanley Cavell. It does not cast doubt on the reality of the world (a classic theme of skepticism, as seen in films from the 1990s like Matrix, The Truman Show and EXistenZ) but rather doubt on humanity and the reality of others. As the replicant Zhora asks Rick Deckard when he unmasks her, “Are you for real?” The process of eliminating replicants begins with detection, a test to prove whether or not they are human. The central point of the film, established (significantly) in the very first scenes, is the basis of the “Voight-Kampff” tests, designed to detect the abnormal, “non-empathetic” reactions of androids. In this vision of the future, as in more recent ones, robots are capable of emotion, humor, social interaction, and even self-awareness. (Rachael is deeply upset when she finds out that she is not human, and the Nexus 6 rebels are aware of their condition and want to change it.) The androids want to improve their situation. This raises the question of the morality of denying them human status, since humanity is in fact defined by the capacity to have feelings and interact with others rather than by modes of production or other criteria. Ultimately, the procedures for defining and limiting what is human (which lead to the elimination of replicants) are themselves inhuman.

The “life paths” of replicants like Rachael and Roy embody the tragedy of those who know that they are doomed—as we all are, programmed for obsolescence. During this same period, in The Claim of Reason (1979), Cavell makes a now-classic parallel between skepticism and tragedy: skepticism has its origins in an attempt to transform humanity into a theoretical problem.

The tragedy of Othello or Lear does not lie in the doubt that pervades their thoughts but in their refusal to acknowledge and recognize others. Othello is lost from the moment when he seeks to know, when his questioning takes the form of skepticism, when he wants “proof.” Science fiction cinema is thus the contemporary form of the expression of skepticism. In Blade Runner, doubt is radicalized, extending to the subject himself: in the final moment of the director’s cut (released in 2008), Deckard realizes, along with the viewer, that he is also a replicant (and that's not a spoiler—everyone knows this by now). But is that what’s most important? As the film shows us, the answer is no.

Human presence

The best response to doubt—the full-scale Voight-Kampff test that Blade Runner turns out to be—is the way we relate to and care about these characters, the androids, who become the most deeply human presence in the story. The response to skepticism, the humanity of these beings, is once again part of the film’s esthetic essence, in the strikingly real, compelling presence of Roy (played by Rutger Hauer), Pris (Daryl Hannah), Zhora (Joanna Cassidy), etc. The women in particular have a (perhaps ironically) superhuman impact, and their predominance, heralding the feminism of Thelma and Louise (also by Ridley Scott, 1991), is certainly the most eloquent response to any doubt about humanity. Consequently, Blade Runner explores a new form of cinematic power, creating a grim background from which emerge strange, spirited and incredibly sensual figures like Pris, with her white face paint and punk-style black-rimmed eyes. The six minutes devoted to Cassidy as Zhora, a snake charmer turned cold-blooded killer, and shot down as she flees, her clear raincoat splattered with blood, are as unforgettable as Roy’s iconic last words. They show that real humanity lies in the capacity to suffer, to bleed, to cry, to refuse to accept death; in the possibility that the film offers its characters to leave their mark, to become a part of us; in such cinematic memories—memories of our lives destined to be “lost in time, like tears in rain.”

The analysis, views and opinions expressed in this section are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policies of the CNRS.