You are here

Pasteur beyond the legend

The expression “Pasteurian revolution” has become commonplace. From the historical perspective of today’s scientists and biographers, what innovations can truly be attributed to Louis Pasteur?

Michel Morange:1 There is much more to be said about the first discovery that made him famous: the demonstration of molecular asymmetry, or chirality – the fact that molecules can exist in two different forms that are mirror images of each other. However, Pasteur only had a very simple model of the phenomenon. At the time scientists talked about ‘molecules’ without really knowing what they looked like. In his view, a neutral, symmetrical shape came into being and, under the effect of the asymmetrical forces of the cosmos that he hypothesised, adopted an asymmetrical form, right or left. He tried all his life to reproduce this conversion in the laboratory but never succeeded.

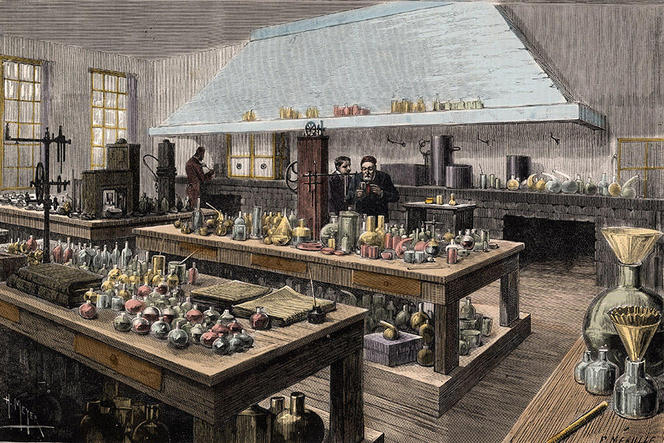

Yet his greatest discovery was vaccination. Edward Jenner is often referred to as the father of vaccination against smallpox because he inoculated patients with a benign bovine disease called cowpox, or vaccinia. Others had already observed its protective effect, but Jenner developed a technique to extend its benefits to the entire population. Pasteur worked on microbes, which opened the possibility of expanding Jenner’s method to all types of diseases. He weakened the microbes in a flask culture and by testing on animals in order to obtain a vaccine. This principle is applicable to any disease, and is the basis of modern vaccination. In addition, he also discovered that microorganisms are responsible for fermentation and putrefaction, among other processes.

How did Pasteur consider his role as a scientist?

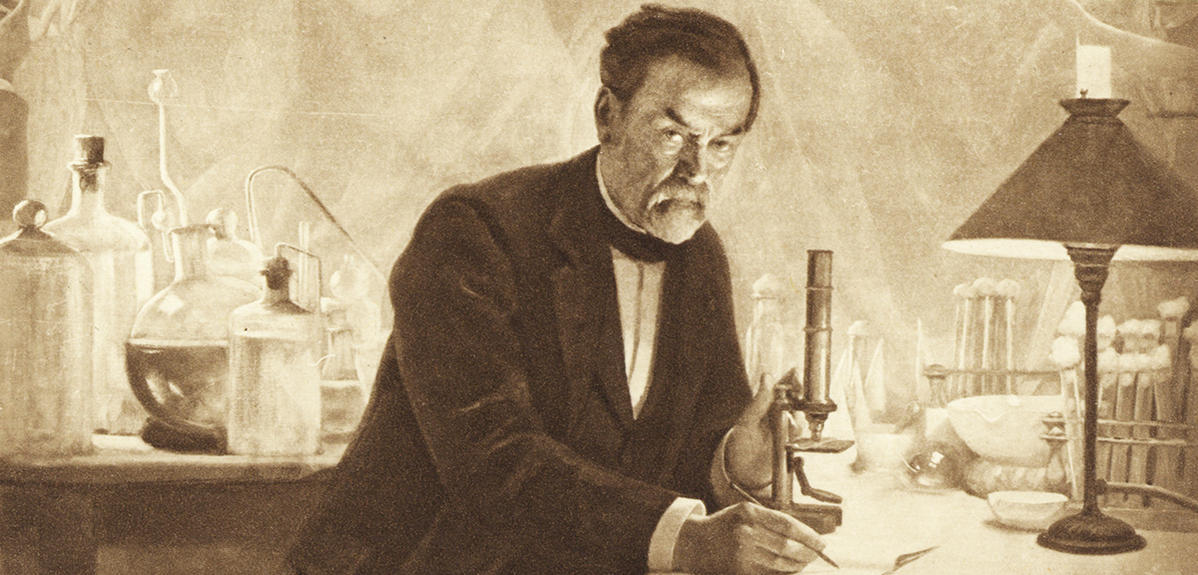

M. M.: First of all, he was a researcher who devoted every day to his work. In fact, his writings about research and education are still valid today. His life goal was to make discoveries whose importance would be recognised by the scientific community, rather than be a benefactor of humanity – although that happened with vaccination, which would offer new preventive strategies in medicine. Secondly, there is the question of profit. At one point, Pasteur filed a patent on beer, which turned out to be highly profitable financially, both in France and other countries. But he also took out others simply to protect his findings, like the one for vinegar, which he soon put in the public domain and thus did not earn him any income. It wouldn’t be fair to say that Pasteur was motivated by the money he could make with his discoveries. He also once told Napoléon III that he did not want to give paid lectures because he preferred to devote all of his time to research.

However, after the Franco-Prussian War, being hemiplegic and disabled, he had doubts about his future and was haunted by the thought of dying and leaving his family destitute. Protecting them became his motivation, but seeking wealth was not part of his mindset and remained foreign to his lifestyle. The son of a tanner, he lived very simply to the end of his life.

As you point out, Pasteur’s legend has given rise to an enduring misconception. In fact, he wasn’t just trying to cure diseases – his main goal was to fight ignorance. Can you tell us more?

M. M.: There is a belief that he was thinking about microbes from the beginning of his research, which is not exactly true. He was not obsessed with microbes and did not immediately embrace the idea that infectious diseases were caused by microorganisms. That idea emerged gradually. When he developed the rabies vaccine, he announced that his primary goal had not been to treat the disease, but that his work was driven by a desire to understand phenomena.

According to his earliest notebooks, he was not interested in spontaneous generation. Still, he was the one who put an end to the virulent debate. What was it about and what were the main issues surrounding this question?

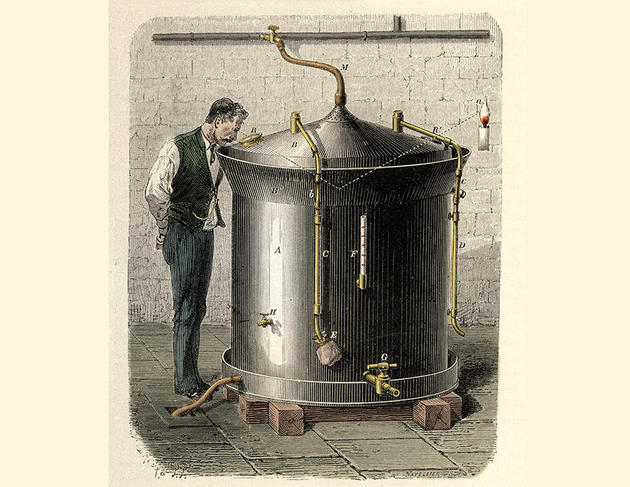

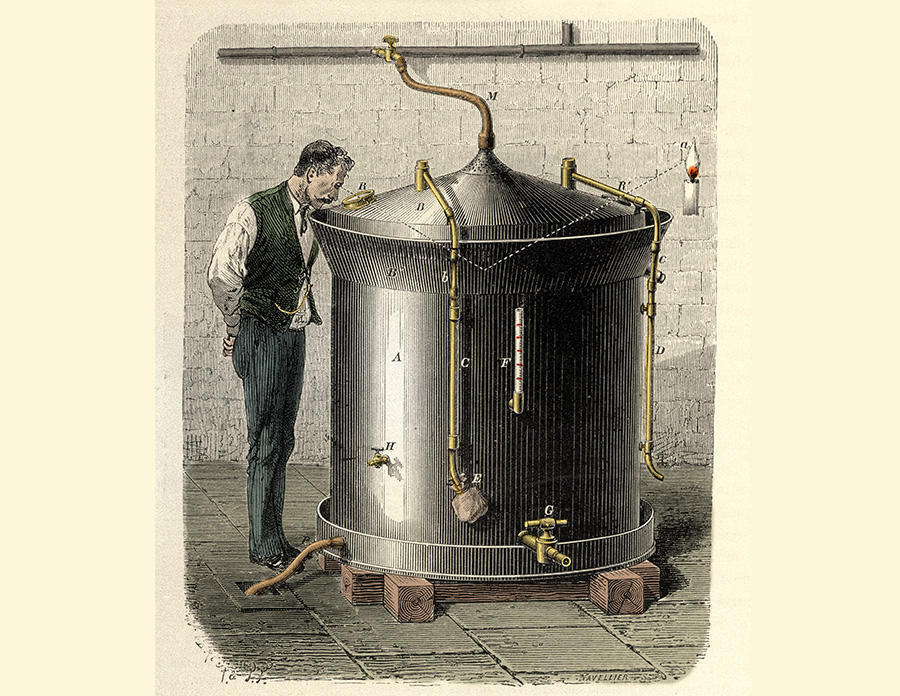

M. M.: According to the very old theory of spontaneous generation, living organisms could arise from the remains of dead ones. It would thus always be possible to obtain yeasts from the fermentation of grapes, but Pasteur showed that if care were taken to avoid all contamination, no yeast would appear. After observing the reproduction of globules (ferments) during leavening, Pasteur became convinced that they reproduced by splitting, which meant that there was no spontaneous generation.

What was Pasteur’s greatest failure?

M. M.: In 1876, Robert Koch published a series of decisive experiments on the microbe responsible for anthrax. It came as a shock to Pasteur, sparking a conflict between the two. Not only had Koch described the microbe and the formation of spores, and transmitted the disease to animals after cultivating the microorganism in vitro, but he also developed a method for verifying that, in certain patients, the pathogen was indeed the cause of the illness. Koch really deserves all the credit. Pasteur was aware of this, but never admitted it and tried to minimise the achievement. This was his greatest ethical failure.

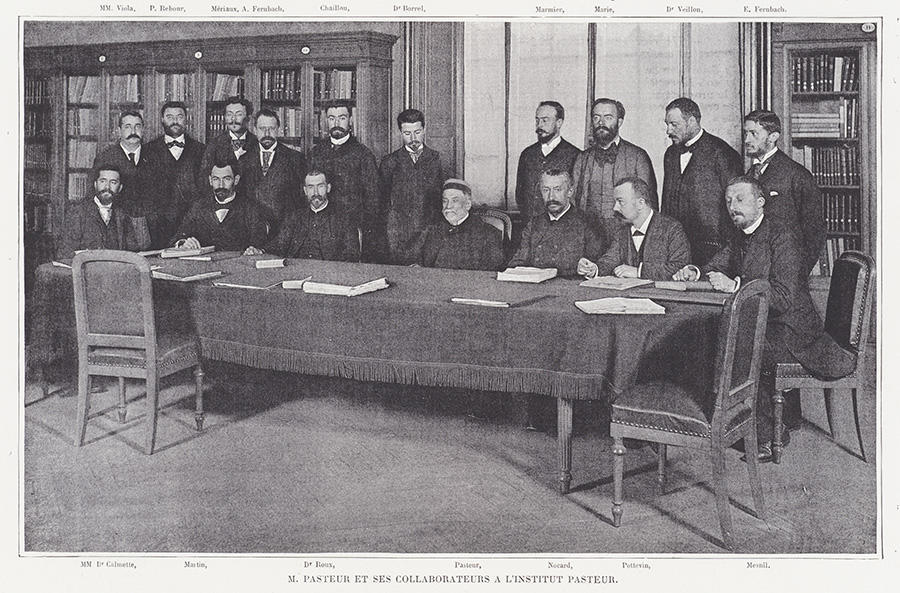

Today Pasteur could be compared to a ‘start-upper’ at the head of an empire. He knew how to draw attention to his work, and did not hesitate to seek political and financial backing to bring his projects to fruition. Where did he get the idea of adopting such modern strategies?

M. M.: At first he did not have good communication skills. For example, he berated journalists who didn’t report what he thought they should. By the end of his life though, he would entertain the press and kindly induce them to say what he wanted! According to the historian Bernadette Bensaude-Vincent, he learned to communicate, no doubt from his many failures in that area. Becoming a public figure also helped.

Pasteur once proclaimed, ‘Ah gentlemen, it is sometimes said that science kills the heart. But look closely at these beautiful phenomena, full of grandeur and mystery, in which God’s purposes are so clearly evident, and you will see!’ Did his Catholic faith influence his scientific approach?

M. M.: Pasteur was not a believer who followed the Church’s precepts to the letter. He worked on Sundays and did not attend mass regularly. He found it intolerable when the Church interfered with scientific knowledge, but never renounced his connection to the Catholic religion. He said that he had faith of the heart. For example, he explained that when one loses a child – he lost three – there is a feeling that it is not the end of everything, that there is ‘something’ after death. He didn’t talk about heaven, but he was convinced that life was not all meaningless.

Louis Pasteur was hailed as a hero in his lifetime. Was he a figure that the political establishment – first Emperor Napoléon III and later the Third Republic – and France needed?

M. M.: He transcended strong oppositions, notably between believers and non-believers before the separation of Church and State. From a political point of view, he responded to France’s need to improve hygiene. He was one of the first to advocate asepsis, a preventive method according to which it is preferable to avoid contact with germs rather than having to eliminate them. Pasteur was acceptable to absolutely everyone, which also explains his place in textbooks and the education system. Later he was upheld as a model by such disparate personalities as Marshal Pétain and Che Guevara!

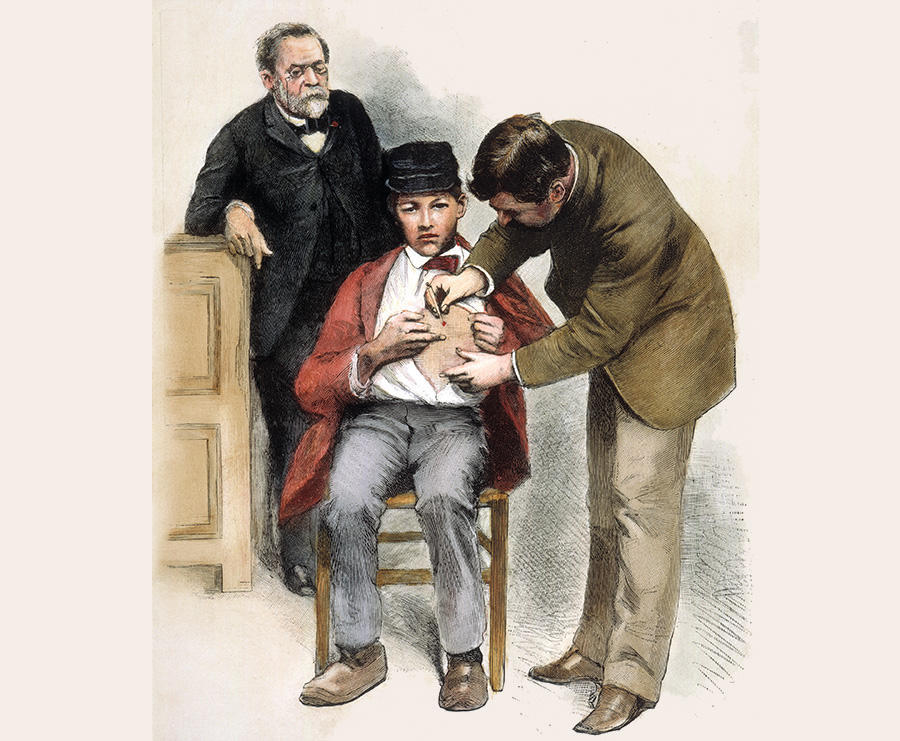

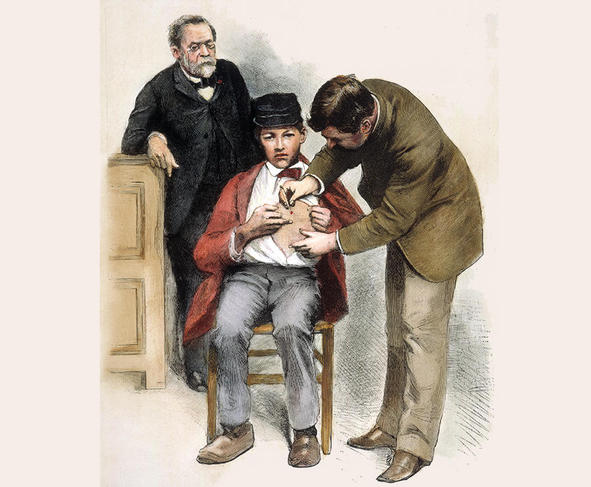

Let’s go back to the discovery that earnt him the greatest scientific recognition. In order to prove the innocuity of the rabies vaccine, and having tested it on dogs, Pasteur undertook to inoculate himself and repeated the experience on the young Joseph Meister without the approval of the doctors involved. Wasn’t that a serious violation of ethics?

M. M.: His vaccination method was quite unusual, using bone marrow from an infected rabbit attenuated by desiccation. He then used extracts that were less and less weakened, finally using the most virulent marrow samples in order to verify that the subject had become ‘resistant’ to rabies. We now know that the last samples used on the young boy would have been fatal if the earlier inoculations had not protected him.

Pasteur, who was not a physician but a chemist, thus used a validation procedure that was ingenious but raised a serious ethical problem: the fact that the vaccinated animals or people didn’t die proved that the vaccine was effective. Otherwise, the last bone marrow injections would have killed them. And the best of it is that it worked!

The trouble with Pasteur’s vaccines was the lack of an explanation for the vaccination mechanism. When he was asked how it worked, he gave different answers. Strangely, at the time no one noticed! It was tempting and enough to think that the attenuated microbe protected the organism. Pasteur said nothing about the body’s immune defences.

You started this book project before the Covid-19 pandemic, which makes the subject highly topical. We can understand people having reservations about vaccines in Pasteur’s time, but are such doubts acceptable today?

M. M.: We need to distinguish between the various criticisms levelled against vaccines, some of which definitely merit further discussion. I started writing this biography four years ago, but as the pandemic took hold it seemed important to emphasise the questions already raised by Pasteur: how can vaccination be performed? How long does the protection last? The immune system is extraordinarily complex and we still do not know all of its intricacies. So when we make a vaccine, we do everything we can to ensure that it’s effective, but we cannot always anticipate the outcome, or predict all the possible side effects. This formidable complexity is the frontier of vaccination today. We may think that we’ve understood everything, but that’s not true! The battle is never completely won, even today. There is no recipe for predicting the success of a vaccine or the severity of its side effects.

Would it be correct to say that in France, in Pasteur’s time, no one else had such a career or achieved such national and international renown?

M. M: There is indeed no equivalent, especially not with such current relevance. This is a good time for us to look back at his life, because there is so much criticism now of the man and his work. We need to re-examine Louis Pasteur and his heritage, without idealising him and dispelling the myths.

- 1. Researcher and academic at the IHPST (CNRS / Université Panthéon-Sorbonne).