You are here

Pangloss: lending an ear to rare languages

Do you know Ubykh, a Caucasian language that slowly declined and finally disappeared due to Russian expansion into the region from the late 19th century? Have you ever heard a song in Na, a Sino-Tibetan tongue still spoken in the mountains of Sichuan, a region of China located to the east of Tibet where Mandarin is gradually establishing itself as the sole means of communication? Together with 170 others, these little-known parlances are now available to all on the Pangloss website, an exceptional body of sound archives of rare and endangered languages collected thanks to the painstaking fieldwork of linguists.

“Of the 6,000 tongues that exist in the world today, several thousand are insufficiently documented or not documented at all," says Alexis Michaud, a linguist at the LACITO,1 the laboratory that initiated the Pangloss platform. “These are non-written and have neither a dictionary nor a grammatical corpus.” Dedicated linguists and ethnologists are attempting to fill this gap by recording tales and stories from the oral tradition, so that they can be transcribed phonetically and reveal their secrets. “Documenting a language usually represents a lifetime’s work,” Michaud points out.

“25 languages become extinct every year”

Until the advent of digital technology, research by specialists usually resulted in the publication of grammar books and dictionaries as well as, less frequently, translated stories for the general public, while the reels of tape bearing vocal recordings ended up gathering dust on shelves or were eventually lost forever. The Pangloss collection, which was launched over twenty years ago, aims to make up for these shortcomings by digitising that goldmine and making it accessible to as many people as possible, including linguists and researchers from across the world – for whom the bilingual French-English website provides dedicated pages and resources – but also, for the first time, interested members of the public.

There is an urgent need for action at a time when linguistic diversity is facing the same fate as ecosystems: it is estimated that 25 languages become extinct every year, and that at least a third of those spoken on the planet will have died out by the end of the century. The decline can be blamed on globalisation, with the tongues of dominant nations taking over from local ones. This for example is the case for Spanish in Latin America, Mandarin in China, Wolof in Senegal, and also Vietnamese in Vietnam, which nonetheless boasts dozens of other languages. However, this is not the only factor. By driving populations out of their own territories, climate change is further accelerating this process.

“Historically, the greatest linguistic diversity is found in isolated areas, such as mountains and dense forests, like the Amazon and Papua New Guinea – the latter boasting more than 800 different languages!” Michaud explains. “With rising temperatures, there is a risk that these regions may become uninhabitable. This is already happening in certain parts of the Himalayas, where melting glaciers are forcing communities to migrate to the lowlands and cities, where they gradually lose the use of their mother tongue.”

3,500 audio and video documents

To save this endangered resource, 3,500 audio and video documents recorded by more than 50 linguists are already available on the Pangloss website, which is hoping to further expand its content over the coming months and years. “Researchers should get into the habit of putting their sound archives online as they work, rather than waiting until the end of their career to get round to it,” the specialist insists. “Never mind if they don’t all have a written transcription yet.” To address this problem, the Pangloss platform is to provide automated language processing software in 2021, which should make the experts’ task much easier. “Until now, it took around at least a hundred hours of recording to train artificial intelligence to make transcriptions of a new language. With the interface we are preparing for the website, based on the latest available technology, one hour will be sufficient. This will be a real revolution,” Michaud enthuses.

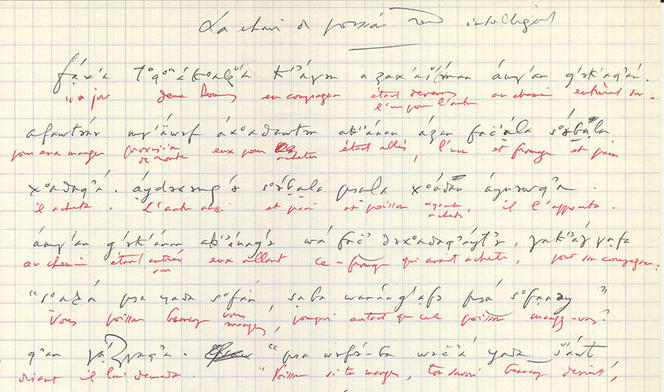

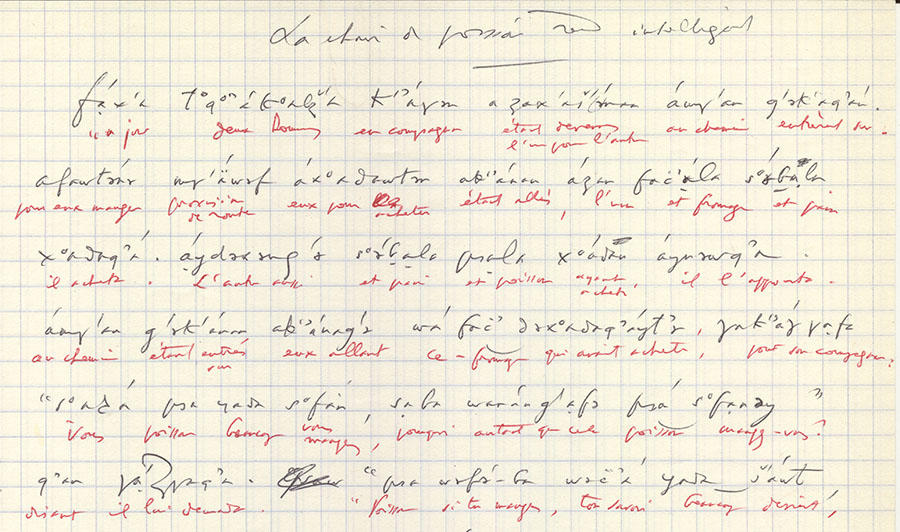

Developed on the open science principle, meaning that the documents put online are under a creative commons license and that anyone can access them freely, Pangloss also aims to be “cautiously collaborative”. “It won’t be possible to modify the documents directly, as on Wikipedia, but we will welcome any suggestions and offers of help, wherever they come from. Especially for translations of documents that don’t yet have one.” Among the many little gems to be found on the site, a story collected in the 1960s from the last Ubykh speaker (“Eating fish makes you clever”) by the linguist and member of the Académie Française Georges Dumézil was, somewhat surprisingly, transcribed and translated thanks to the unexpected assistance of a student from California (US), who had learnt this extinct language all by himself using the dictionary and texts published by the very same Dumézil.

- 1. Langues et civilisation à tradition orale (CNRS / Université Sorbonne Nouvelle / Inalco).