You are here

Unlocking the Secrets of Click Languages

The Tanzanian Rift region has long been a source of fascination for linguists. “It’s the only part of Africa that brings together the four major families of African languages,” explains Didier Demolin, a researcher in experimental phonetics and director of France’s Institute of Linguistics, General and Applied Phonetics (ILPGA) in Paris. “They include the Nilo-Saharan languages like Maasai, the Niger-Congo group like the Bantu languages, Afro-Asian tongues like Iraqw, which we are studying, and the Khoisan family, which is mainly found further south but is present in Tanzania through Hadza, with some one thousand speakers.” Iraqw and Hadza are two complex-consonant languages of the Tanzanian Rift that are of particular interest to specialists for their incredible richness. “Hadza is part of the Khoisan group, which can have as many as 130 phonemes, compared with an average of 30 for the world’s other languages,” Demolin notes. “By themselves they represent a good half of the phonatory capacity of humankind – in other words half of all the phonemes that our vocal tracts and articulators are physiologically capable of producing!” Hadza uses 65 different consonants, including a dozen clicks, short percussive sounds produced by a reduction of air pressure in the vocal tract. Iraqw is characterised by “ejective” consonants, veritable blasts of sound that are especially intriguing to phoneticians.

Delving into the structure of these two languages to analyse their biomechanical characteristics was the goal of an unprecedented mission carried out in February of this year by an international research team led by Demolin and his associate of 30 years Alain Ghio, an engineer specialising in phonetics at the Speech and Language Lab (LPL)1 in Aix-en-Provence (southeastern France). “Iraqw and Hadza have already been the subject of in-depth linguistic studies on their syntax, phonology and vocabulary,” Ghio says. “What we wanted to do was to make a precise instrumental description of these languages and the way their speakers produce those remarkably distinctive phonemes.” To that end, the two scientists went to the field with an array of instruments that are normally found only in phonetics laboratories, “amounting to 70 kilos of equipment per person, to be carried all the way to the villages of Kwermusl and Mwangeza, in the heart of the Tanzanian bush, where we conducted our measurements and recordings!”

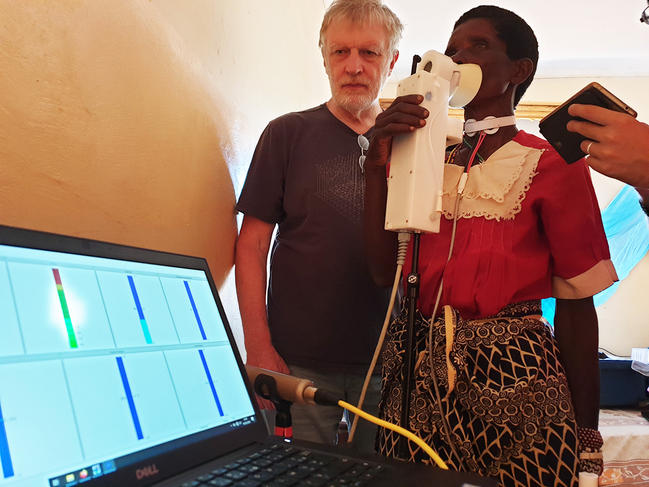

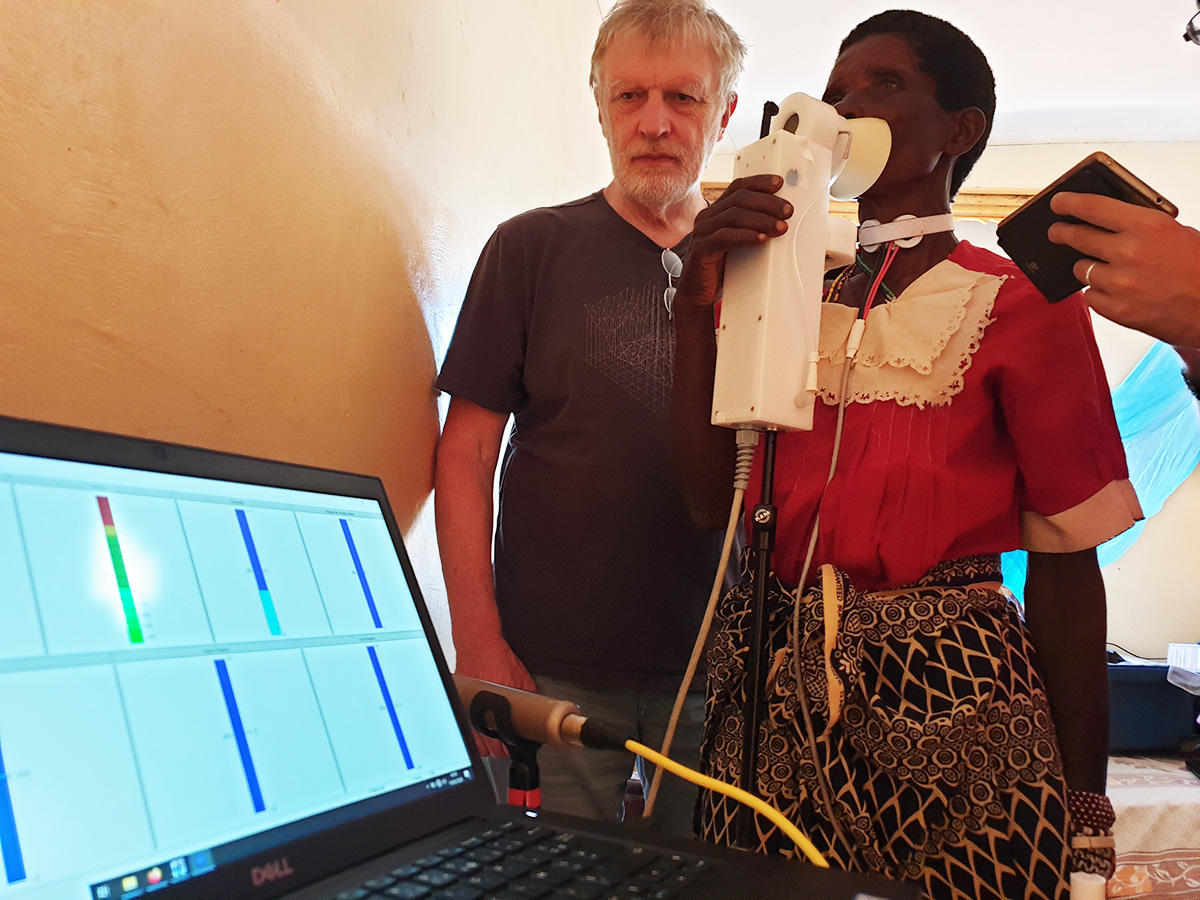

Among the devices they brought with them was the Rolls-Royce of phonetic studies: the assisted vocal evaluation (EVA) machine, designed by Ghio and the late Bernard Teston, which precisely assesses air flow and pressure in the vocal tract – one of the most powerful aerophonometry tools available today. “To perform the measurements, the speakers are equipped with a mask and a disposable sensor, which they position themselves in the oral cavity through the nose,” Ghio explains. Another technique deployed at the same time, electroglottography, “consists in placing two electrodes on the neck over the trachea, on each side of the vocal chords, in order to evaluate their activity and the movements of the larynx,” the engineer adds.

To complete the panoply, a high-speed camera was used to record the volunteers’ lip movements in “labiofilms” with a very high frame rate (300 fps per second), along with palatography to observe the contacts between the tongue and palate during the articulation of a sound. “The tongue is dyed black with a blend of oil and medicinal charcoal, and we then take a photograph of the palate using a mirror,” Ghio reports. “That way we can see if the articulation occurs just behind the teeth or a little further back.”

In all, a dozen Hadza speakers and the same number of Iraqw speakers were recorded. “That’s already a lot, considering the time it took – half a day for each person – and the technical challenges we had to overcome. To power the machines, all we had was a solar panel and an electric battery,” the engineer points out. Not to mention the recordings ruined by untimely interruptions from crowing roosters… As the researchers put it, “the measurements were made under conditions falling far short of laboratory standards!”

The resulting hundreds of recordings will take months or even years to analyse – “we’ve got enough to write several dissertations!” Demolin says. But in the meantime, the initial observations have proved quite surprising for the two French researchers and their Dutch, Canadian and American colleagues. “In speaking French and other European languages in general, there is very little distinct movement of the larynx,” Demolin reports. “But in these tongues the larynx is in constant upward-downward vertical motion. This happens in particular with the ejective consonants of Iraqw, and that’s part of what we set out to verify with our instruments. Yet to our great surprise, we also recorded horizontal, front-to-back movements of the larynx that had never been clearly observed until now! For us Europeans, these would be similar to how the larynx moves when we swallow.”

It is also worth noting that in Iraqw, whose ejective consonants are formed by the closing of the vocal chords and vertical movements of the larynx, there is no front-to-back motion of the tongue, which is common in the Nilo-Saharan family, for example. “These languages seem to avoid combining articulator movements that would prove difficult in sequence,” Demolin explains.

“The value of this type of study goes beyond the linguistic and cultural, and even beyond human phonetics in a broader sense. The biomechanical analysis of the languages of the Tanzanian rift, taking each class of sounds in turn, will make it possible to compare and retrace the contacts between populations over the course of history, showing which languages have (or haven’t) borrowed phonemes from other groups,” concludes Demolin, who is already planning his next field mission. The populations of the Tanzanian bush have not seen the last of the French scientists and their strange instruments.

- 1. Laboratoire Parole et Langage (CNRS / Aix-Marseille Université).