You are here

Jean Rouch: a film-maker, ethnologist and explorer

Jean Rouch was a born-explorer. The son of a meteorologist, oceanographer and writer, he grew up in a family of scientists, artists and adventurers. Although used to travelling from an early age, he was first attracted to the hard sciences and joined the Ecole Nationale des Ponts et Chaussées, where he graduated as a civil engineer in 1941. As a student, he met the French ethnologists Marcel Griaule and Germaine Dieterlen, who introduced him to the magic of Black Africa and the Dogon people of Mali. Yet it is "a coincidence of history"—France was occupied at the time—that would take him to build bridges in the French colonies of West Africa. In Niger, he discovered the Songhay tribe and their world of magic. He initiated one of his first ethnographic studies, whose results he regularly submitted to Griaule, before publishing an article on Songhay animism—or attribution of a living soul to inanimate objects and natural phenomena—in the journal Notes Africaines upon his return to Paris.

In the wake of the Second World War, where he fought (and blew up bridges!) as a civil engineer, Rouch set off to Africa with his friends Pierre Ponty and Jean Sauvy to travel down the river Niger in a canoe. There they sent regular reports of their expedition to the French press agency, AFP, which would later earn them the very first Liotard Prize by the French Explorers Society. It was on this occasion that Rouch shot his first films, including, in 1947, "In the Land of the Black Seers," about a hippopotamus hunt with the Sorko, a group of Songhay fishermen.

He joined the CNRS the same year as a researcher in ethnology and pursued his work on the Songhay in preparation for his thesis. Having failed to complete it within the allocated three-year deadline, he was dismissed from the institution, which he reintegrated a few months later. He eventually defended his thesis on Songhay religion and witchcraft in 1952 and became a doctor in ethnology.

Fascination for rituals and spirit possession

In addition to his many subjects of research, Rouch was fascinated by trance phenomena and split personality, which are the focus of his work. "Initiation to the Dance of the Possessed" in 1949, would be followed in 1955 by " Masters of Madness." The latter, showing a ceremony of spirit possession by migrant workers from Niger performing a Hauka ritual in Accra (Ghana), won an award at the Venice International Film Festival in 1957. It marked a milestone in the career of the ethnographer who, in 1971, also released "The Ancient Drums" about a dance of possession in Niger.

"Battle on the Great River," again depicting a hippopotamus hunt on the river Niger, and "Cemetaries in the Cliff," a funeral in the Cliff of Bandiagara (Mali), bear witness to Rouch's long-standing interest for the Dogon people, as does "the Dama of Ambara," which, in 1974, recounted an end-of-mourning ceremony where masks played an important role. With Dieterlen, Rouch also attended and filmed the Dogons' Sigui rituals, which only take place every sixty years. Their work is all the more invaluable as the Dogon culture is now under pressure from polical and ethnic tensions, as well as from the predominance of Islam in the region.

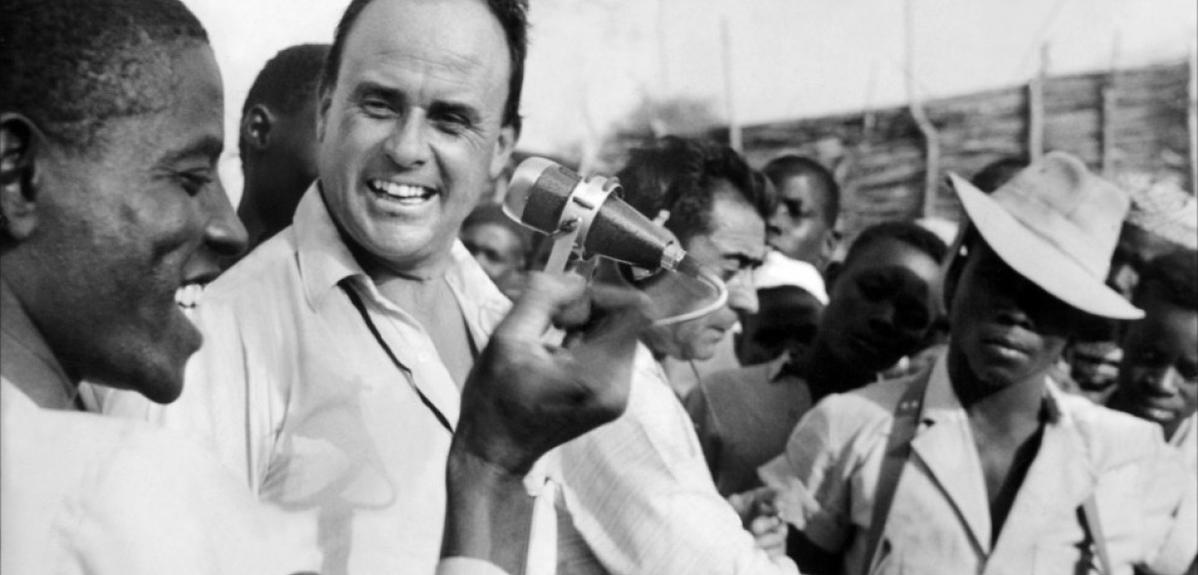

More than a testimony though, Rouch's work introduced a new concept, that of "shared anthropology," consisting in making films with—rather than about—people, and involving them in the process. A combination of fiction and reality, his work showed live situations and endeavored to encourage action. His hand-held camera was ubiquitous and always acknowledged, in order to facilitate interaction with those being filmed. "When you show an image on a white wall, people see themselves. And all of a sudden, they understand what you've done. They don't speak your language, but they can read the message," he said. The father of a genre known as "cinéma vérité," or "truthful cinema," Rouch sought to reveal the truth as objectively as possible.

An insatiable appetite for learning

From the Dogons, Songhay and Koromba of Mali to the Gurma of Burkina Faso, and the Doukkala of Morocco, his curiosity knew no bounds—even extending to reverse ethnography. "Little by Little," for example, is a humorous account of how an African saw Parisian life in the late 1960s: "Europeans who go to Africa come to visit the bush ... Because they've no more room. Not a forest to be seen." A life that has not changed much since then: "At the weekends they go to the country. It rains. The roads are bad. But they still go."1Rouch also kept experimenting and innovating, working on several projects at the same time, and improving on existing productions, which is why nearly one third of his 170 or so films remain unfinished: "I'm terribly wary of people who one day stop learning and become professors ... As far as I'm concerned, I could learn and discover for ever." In the late 1950s, with other ethnologists, he set up the Ethnographic Film Committee (CFE) at the Musée de l'Homme in Paris to promote documentaries and strengthen the link between cinema and the social sciences. In 1969, he founded a cinema section within the Université de Nanterre's social sciences department. This was followed in 1976 by the introduction of a post-graduate diploma in cinema research, which he supervised, with a view to training "film-makers-cum-researchers" to improve coordination between images, words, and narration.

1975 saw the birth of the "Cinéma du Réel" festival, supported by the CFE and the CNRS, before specialized training in documentary filming was introduced in the early 1980s, at Rouch's initiative. From 1986 to 1991, the ethnologist headed the French film library, Cinématèque française, and made his last film, "Dream Stronger than Death," in 2001. Three years later, having decided to stay in Africa after a tribute held in his honor in Niamey, Rouch died in a car crash in Niger, which had so inspired his life and works: "Niger ... is the land of nowhere. And in the land of nowhere, one can dream, invent." Dreaming and inventing films like so many works of art: one of Rouch's legacies to would-be film-makers, ethnographers, humanists and adventurers walking in his footsteps.

- 1. "Media, Modernity and Technology - The geography of the new" by David Morley. Routledge 2007.