You are here

A Different Perspective on African History

You were recently elected to the Collège de France. What are the key issues regarding the current teaching of African history?

François-Xavier Fauvelle:1 This is an enormous responsibility. I am pleased but also quite intimidated! Africa is seen as a continent that “has remained stuck in history” or will never be more than the eternally primitive cradle of humanity. The main challenge is to combat these clichés, with a line of thought that is both pedagogical and based on the most advanced research. I believe that I have succeeded in my lectures and books for the general public, in particular my latest,2 which retraces 20,000 years of African history, based on contributions from the world’s top specialists. In the same spirit, I would like to organise group seminars and invite many researchers to join me in the marvellous showcase that is the Collège de France. We must show that research on Africa is a multifaceted, dynamic field, echoing the diversity of the historical accounts that can be written about it. In the same sense that a “history of Europe” would be fragmented, that of a geographical space three times larger cannot be reduced to a few generalisations that are naïve at best, and at worst condescending.

How do you hope to combat these preconceived ideas?

F.-X. F.: Through teaching, especially given that a large part of the public is avid to know more. To say that Africa has no history is quite simply wrong from a factual point of view. One can perfectly well recount its political regimes, its economic and cultural activities, or its demographics and population movements. Another prejudice is more insidious because it bears a cloak of false benevolence, namely that Africa is primarily the “continent of our origins”.

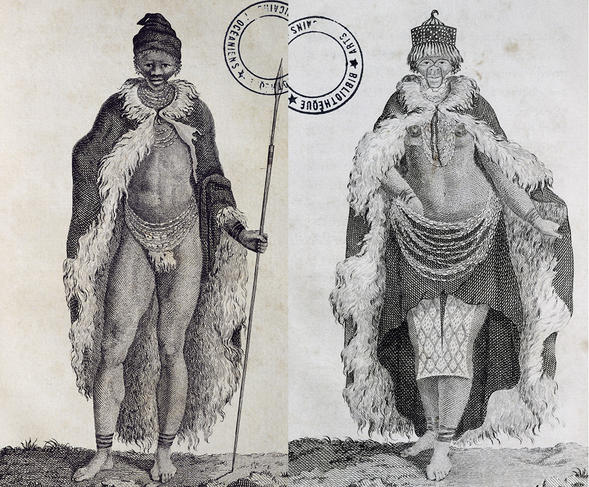

For one thing, this idea overlooks the fact that history has continued to the present day. There is an entire prehistoric period, medieval times and a modern era to recount. Secondly, and no doubt worse, this image tends to trap the continent in a primitive, naturalised and ethnicised representation, which can even be seen in the exhibition designs of our museums. The African is presented as the “noble savage”, still vulnerable to the vagaries of his environment, still a bit helpless without the aid of white European settlers to bring him progress and civilisation…

These stereotypes owe a great deal to the fact that African history was for a long time conceived in relation to – and measured against – European history. This approach imposes an inapt analytical framework on the continent, rather than embracing its specificity.

Why can’t African and European history be compared?

F.-X. F.: Everything can be compared, but interpreting local realities in terms of what happened elsewhere always leads to misconceptions. Let’s take the example of Eurasia, whose societies have generally gone through the same stages of development. The hunter-gatherers invented the first tools, then became sedentary and developed agriculture and livestock breeding, etc., to the point that by the Middle Ages the hunter-gatherer lifestyle had disappeared there completely. In Eurasia this evolution is the same nearly everywhere, with little variation in the order of the revolutions. But Africa does not follow this pattern at all! On the contrary, the continent is characterised by an incredible diversity of sociocultural trajectories and evolutions that cannot be reduced to the dynamic of European history – Palaeolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic… If you apply this evolutionary pattern on the continent, it all becomes incomprehensible. And there has long been a temptation to falsely deduce that Africa has not evolved, that history has no significance there – as though it had only one single meaning. In fact, we must learn to invent new analytical frameworks for Africa, and to reverse our perspectives: why does Eurasian history present such a consistent uniformity of trajectories, techniques, kinship systems and languages? The African continent is proof that there was another possible path.

In the current context, should we consider these analyses as a plea in favour of better recognition of specificities, and against a universalism that is blind to its own cultural anchoring?

F.-X. F.: Not necessarily. For example, I got a lot of attention for talking about the “African Middle Ages”. Although this chronological designation corresponds primarily to a European situation, for me that is not the main issue. In any given period, the different regions of the world necessarily remain interconnected. To place them in the same temporal reality, a kind of “global Middle Ages”, so to speak, is paradoxically one way to uphold a multipolar conception of history.

It is true that we must distance ourselves more from an overly Eurocentric vision, one that makes Africa a sort of “province of the world”. In fact, one is the periphery of the other, depending on your point of view. This is more important than a semantic debate about our chronological conventions. Concerning the questions of identity and conflicts of memory in our society, it seems to me that we would benefit from accepting a plurality in the narrative that we make of our history. Everyone chooses their ancestors in their genealogy, depending on the current situation. Each collective group, be it a family or a nation, builds their own memory, a historical novel that is open enough to allow the incorporation of new events and characters. These accounts do not challenge the community’s capacity to project itself as a “we”, which can always be redefined.

Your approach to history juggles between facts, their representation and their crystallisation in the collective memory…

F.-X. F.: That no doubt comes from my early studies in philosophy! The experience made me very sensitive to methodological questions and the necessity of trying different points of view. When I returned to studying history, after taking a PhD and a string of odd jobs, my work focused on the representation of the Khoisan populations in European sources between the 15th and 19th centuries.3 One example is the famous Hottentot, often exhibited and caricatured on our shores. That led me to conceive a kind of history that is first and foremost a history of our representations, rather than events. Perhaps more than any other continent’s, African history has been polluted by categories that have nothing natural about them: “races” and ethnic groups, linguistic communities, and even boundaries that at first had no meaning for the local populations, even though some ended up adopting them. This initial work taught me to familiarise myself with the development of “knowledge” and “facts” that ultimately blur our perception of things. Any attempt to trace the history of Africa eventually comes up against a barrier of epistemological obstacles that have to be deconstructed in order to reveal – insofar as possible! – a segment of reality.

In short, you recommend the writing of a “history of history”. Is the narrative account of any use in research?

F.-X. F.: Yes, of course, narrative research is part of historical research. It consists in finding the form of recounting that does the most justice to the facts. For example, history is most often related in chronological order, whereas historical investigation starts from the present. It takes off from a source that is necessarily current, a remnant or an archive, and goes back into the past. Consequently, the “natural ” order of our access to events is, paradoxically, not that of the chronological account. In order to recount, not how an event happened, but how this is known, it is necessary to describe the investigation. There is nothing revolutionary about it: it’s the archaeological method. In fact, that’s why I turned towards archaeology very early on. I wanted to be close to the material sources, to bypass the strata that accumulate between the past and the present. Not because these remnants represent more authentic “historical facts”, as they must also be deciphered, to understand how they came down to us. But the materialities allow us to expand the documentation. I lived in South Africa and Ethiopia for several years, gaining valuable early experience as the head of the French Centre for Ethiopian Studies (CFEE), where I coordinated collective projects and organised missions. Also, there was tremendous potential there for studying the Middle Ages.

Why is your research on Ethiopia particularly important for you?

F.-X. F.: It is an amazing country. During the medieval period, all of the major cultural movements seem to have crossed paths there, whether it be Islam, Christianism, or paganism… It is also one of the very few regions where the use of writing has been continuous since the 8th century BC. Except for North Africa – Egypt, for example – there is no equivalent on the continent. That’s already an enigma in itself. In addition, the presence of numerous written sources has made our reconstitution of the past considerably easier.

With the risk, however, of making Ethiopia a kind of isolate. This is often a source of bias when there is more information accessible on one country than on the others. The accumulation offers an ever sharper, more precise image of that country, while our representation of its neighbours remains sketchier. We must keep this documentary uniqueness in mind to avoid falling into the trap of particularism. In fact, you cannot understand anything about Ethiopian Christianism or Islam if you disconnect them from their Mediterranean, Middle Eastern or African counterparts. In the same way, we know that many writing systems have existed in Africa, but most African societies have preferred oral traditions. Once again, it would be an error to consider writing a “natural” step in the development of a culture. The question should be: why wasn’t writing deemed necessary even though it was available? What political systems and social customs were able to emerge in this context?

You have also worked a great deal on Morocco…

F.-X. F.: Indeed, I am heading several projects at the Sijilmassa site. This medieval Islamic city was a gateway for the caravans that wanted to cross the Sahara. My work has always focused on what one could call “connected Africa”: the Africa of commercial, cultural and ideological exchanges. The trans-Saharan trade, which is still under-documented, bears witness to this interconnection between all the regions of the continent. Contrary to a common preconception, it would be deceptive to contrast a supposedly white and Mediterranean Africa with a Sub-Saharan or “black Africa” that is supposedly completely different. The ruins of Sijilmassa make it possible to link the two within a more complex geography. At the same time, the site thwarts many expectations: it is very badly eroded and has been looted over the centuries. In particular, it was highly idealised in travellers’ accounts and in the documentary sources we have found. It’s still very difficult to synchronise all of this information, to produce a consistent vision of the city in the Middle Ages and its influence on the rest of the continent. But we’ll take as much time as needed. Morocco has the advantage of being relatively stable politically, so we can plan on continuing our research for several years.

What remains to be discovered in Africa?

F.-X. F.: A lot of things! By definition, sometimes we don't even know what we should look for. But there are also sites that we have heard about and have not found. Some are mentioned in written sources but have never been located, like the capital of the kingdom of Mali in the 14th century. It was one of the most famous kingdoms of that period, and yet no one can say with certainty where the city is. This is typical of research on Africa: a site may be right under our nose but we have no way to connect it to the written sources. Or we keep looking in the wrong area because it fits our assumptions. And sometimes the city has simply disappeared because it was built in an unstable environment. All of the specialists on ancient Africa have had their ideas about the Malian capital, but it continues to elude us. It’s a stinging reminder that we will always need pluridisciplinarity and a variety of skills, but also an attitude of humility in relation to this continent rich in history.

- 1. François-Xavier Fauvelle is a CNRS senior researcher and director of the TRACES laboratory (Travaux et Recherches Archéologiques sur les Cultures, les Espaces et les Sociétés – CNRS / Université de Toulouse Jean-Jaurès / Ministry of Culture).

- 2. L’Afrique Ancienne – De l’Acacus au Zimbabwe, collective, Éditions Belin, 2018. For further reading: The Golden Rhinoceros, Alma Éditeur, 2013, and À la Recherche du Sauvage Idéal, Éditions du Seuil, 2017.

- 3. L’Invention du Hottentot – Histoire du Regard Occidental sur les Khoisan (XVe-XIXe Siècle), Éditions de la Sorbonne, 2002; rereleased in paperback, 2018.

Explore more

Author

Fabien Trécourt graduated from the Lille School of Journalism. He currently works in France for both specialized and mainstream media, including Sciences humaines, Le Monde des religions, Ça m’intéresse, Histoire or Management.