You are here

AIDS, globalisation's first pandemic

How did your research career lead to your writing about the global history of AIDS between 1981 and 2025)1?

Marion Aballéa2: I started studying AIDS diplomacy, in particular citizens’ movements targeting diplomatic interests, such as demonstrations, peaceful or violent, aimed at embassies and consulates. For example, when the United States banned people living with HIV from entering the country, a mobilisation effort arose, gaining momentum in 1990 at the International Conference on AIDS in San Francisco, which many AIDS sufferers were unable to attend.

As my research progressed, I noticed the scarcity of studies – not just in French, but also in English – taking a historical approach to the political, social, economic and international issues concerning the HIV/AIDS epidemic. It prompted me to take a closer, more in-depth look at this history.

Research has indicated that sporadic HIV outbreaks occurred in Equatorial Africa in the early 20th century. How did it transform from a local disease into a pandemic?

M. A.: The virus had been spreading in a limited way for at least 30 or 40 years, and probably began its pandemic expansion starting in the 1950s – first in central Africa, due to colonial dynamics and violence as well as a rural exodus that led to a concentration of population, especially men, in cities like Kinshasa (capital of the present-day Democratic Republic of the Congo – Ed’s note), which no doubt served as an incubator.

The first isolate of the virus in a blood sample was identified in 1959 in the Belgian Congo, and the records include cases of Europeans, for example sailors, doctors or nurses, who after returning to Europe in the 1960s or 1970s, died of diseases that were then unidentified but whose clinical picture points to AIDS. Later, the workings of globalisation allowed the virus to spread gradually in the 1970s, then more massively in the early 1980s, in a postcolonial and Cold War context.

Ultimately, the disease was first identified in the US…

M. A.: Yes – in fact, as early as 1981, in California and then in New York, doctors began to send consistent evidence of a new and mysterious syndrome to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) in Atlanta (Georgia). The CDC then commissioned investigators to interview the first patients and try to understand the dynamics of this emerging disease. Soon after, the gay community raised the alarm bells with the authorities about what some saw as a direct threat to their survival.

At the time no one knew anything about the disease or how it was transmitted, let alone how to treat it. How was the response in the Western countries organised?

M. A.: First of all, the homosexual communities rallied together in an endeavour to raise awareness. As early as 1982-83 they were sharing advice on safe sex and encouraging people to limit the number of their sex partners – and once the infectious nature of the disease was confirmed, to use condoms.

As for the public authorities, their response was much slower, and in some cases influenced by the ideological preconceptions of the governments in power, especially in the United States under the Reagan administration. Generally speaking, the same ‘slow to the mark’ reaction could be observed in all industrialised countries: it wasn’t until 1986 that a serious effort, varying in scope, really took off.

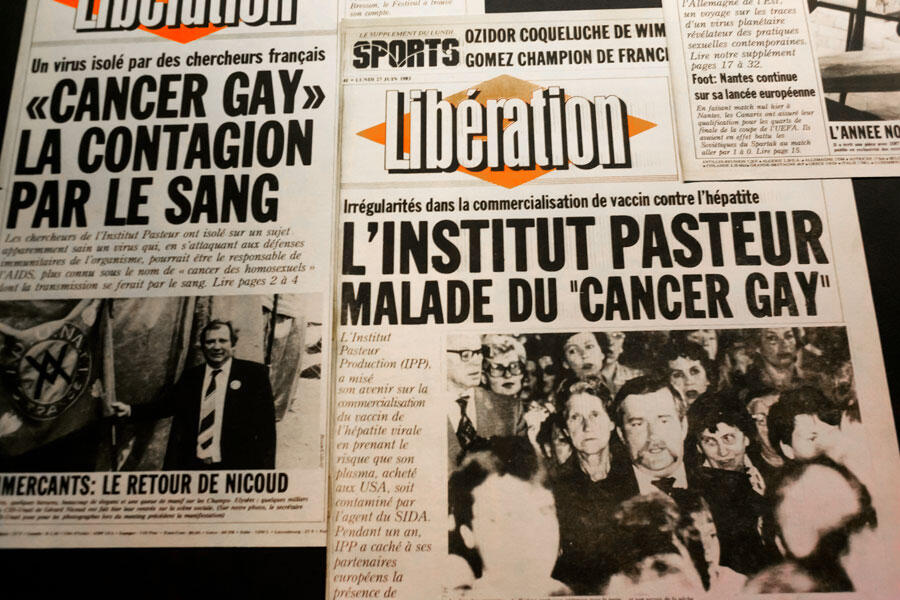

Lastly, in terms of the media, a veritable frenzy started in 1983-84 about a fatal disease that no one fully understood and that bore a perceptible stigma. The earliest reports, showing patients at the end of their lives, skeletal, dying, echoed the entire iconographic repertoire and cultural references of the concentration camps. It created a kind of panic, a vector of stigmatisation and rejection of the most exposed populations.

And what happened in Africa?

M. A.: On the African continent, where the condition was not officially identified until 1985, there was initially a form of denial, due to economic concerns but also prejudices regarding a disease of ‘depraved’ Westerners – homosexuals and heroin addicts.

Moreover, the focus was on the West. Even though the number of cases continued to rise in Africa, the international organisations, in particular the WHO, were slow to assess what was happening outside the industrialised countries. Finally, in 1986-87, an international programme was initiated to fight the pandemic. It was only when the situation improved in the wealthy countries, with the advent of triple therapies in the mid-1990s, that Africa became a centre of global attention and efforts were made to combat the outbreak there.

What role did patient groups play in the comprehension and management of the pandemic?

M. A.: The earliest association formed to fight AIDS was the Gay Men’s Health Crisis (GMHC), founded in New York in January 1982. In France, the first organisations appeared in 1983. AIDES was launched in 1984. Very early on, all of these groups were questioning the doctor/patient relationship, the role of sufferers in research and the means of access to more or less promising medications.

These issues gained momentum, and above all real prominence with the founding of Act Up New York in 1987. Activists became involved in the scientific activities concerning AIDS, including clinical trials and the first treatments. They also sought seats on committees formed to fight the disease, campaigned for faster approval of drugs, and broke down the doors of laboratories – sometimes literally – in attempts to force researchers to disclose their trial results, or release medications still under evaluation for compassionate use.

This became a fundamental legacy for the history of public health on a national and international scale, laying the foundations for what was termed the ‘expert patient’.

Did the arrival of triple therapies in the mid-1990s calm this militant fervour?

M. A.: The arrival of triple therapies, which proved to be the first effective treatment despite sometimes severe side effects, marked a true turning point. Many patients who thought they were terminally ill were once again looking to the future. But mobilisation continued unabated. Activists in France were up in arms against the idea – briefly put forward by the Ministry of Health for fear of a shortage of antiretroviral drugs – of a lottery system to select the patients who could receive treatment.

In addition, sufferers continue to be involved in clinical research aimed at reducing side effects and improving quality of life, or in the fight against discrimination. Ultimately, even though the situation is becoming less urgent in the richer countries, the militant struggle is shifting to countries that lack access to antiretrovirals, especially on the African continent.

Have effective, better-tolerated treatments made HIV invisible?

M. A.: Yes, to some extent. Since the mid-2000s, HIV has clearly lost visibility in the northern countries, where hardly any AIDS-related deaths are recorded. There are fewer prevention campaigns and the younger generations, who have never known AIDS as a life-threatening disease and an irreversible death sentence, who have never been socially acquainted with prevention campaigns, are ill-informed today.

However, there are still contaminations. In France there are about 6,000 new cases of seropositivity each year. It seems that a floor rate has been reached since 2010, despite treatments that make the virus undetectable and untransmittable, and notwithstanding pre-exposure and post-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP and PEP).

At the same time, popular culture is showing a renewed interest in the history of the HIV pandemic.

M. A.: Indeed, until the mid-1990s, many cultural productions took an interest in the subject of HIV, with major films and book releases, intended for activists or the general public. Then the theme more or less faded from the scene, returning to the spotlight in the mid-2010s.

Today there are two different generations expressing themselves: those who experienced AIDS in the 1980s, who needed to observe a period of mourning for both personal and political reasons, and the generation now in their forties, who weren’t directly involved in the early days of the epidemic but are embracing its history, which they lived through as children or teenagers. Today there is also the question of heritagisation, at the risk – as some people fear – of fossilising the history of AIDS and considering the pandemic as a thing of the past.

While HIV/AIDS clearly marked the end of the 20th century, the Covid pandemic will be indelibly associated with the early 21st century. Have we learned anything from the former to help fight the latter?

M. A.: That’s a complex question. I would tend to say no, even though we have to be cautious and bear in mind that these are two very different diseases. The Covid pandemic gave rise to very restrictive measures including isolation, lockdowns, curfews, etc., whereas the HIV activists were strongly against coercive measures like mandatory testing and travel restrictions, preferring an approach based on awareness and informed consent. Even though there was obviously no risk of transmitting HIV through the air we breathe, as is the case with Sars-CoV-2, in 2020 UNAIDS warned of the risk of challenging some of the achievements of the fight against AIDS, specifically in terms of patients’ rights.

Moreover, even though the AIDS pandemic had demonstrated the importance of a concerted international response, it did not prevent a degree of discord in the early days of Covid-19. Nor did the unprecedented efforts since the 2000s to distribute antiretroviral drugs in the Southern Hemisphere prevent the re-emergence of a North-South treatment gap in terms of vaccine distribution.

This question of international solidarity is cruelly brought up to date with the announcement of the withdrawal of the US from various organisations fighting AIDS. What are the stakes of a freeze on American funding for USAID, and in particular for PEPFAR3?

M. A.: In the past 20 years the United States has taken on a decidedly central role in combatting HIV. In 2003 President Bush approved a $15 billion funding package that changed the face of the fight against AIDS and contributed greatly to the decline of the pandemic starting in the mid-2000s. It is now estimated that 50 to 60% of the world’s anti-AIDS funding comes from the US. Right now the situation is unclear, with the announcement last January of a total suspension of funding, followed a few days later by an ‘exemption’ for programmes that help save human lives.

But what is certain is that Trump, with his businessman’s mindset, does not see the fight against HIV as ‘profitable’ for the US. And if American funding were to disappear, the consequences could be tragic: UNAIDS predicts six million additional deaths by 2030, and the possibility of dropping below epidemic thresholds would be all but unattainable.

For further reading

Iron and cancer, a balancing act

Bacteriophages: medicine goes viral

Pharmacognosy brings nature to our medicine chests

- 1. Une histoire mondiale du sida (1981-2025), Marion Aballéa, 328 pages, CNRS Éditions, March 2025, €25 (in French): https://www.cnrseditions.fr/catalogue/histoire/une-histoire-mondiale-du-...

- 2. Researcher at the Lab for Interdisciplinary Cultural Studies (LinCS – CNRS / Université de Strasbourg) and lecturer in contemporary history at the Université de Strasbourg.

- 3. President's Emergency Plan For AIDS Relief (PEPFAR): launched in 2003 by US President George W. Bush, this plan to combat AIDS has since received more than $100 billion in public funds and takes action in more than 50 countries. See https://tinyurl.com/pepfar-sida