You are here

The Legacy of World War I

November 11, 1918. At 11:00 a.m. sharp, the bells of all the churches in France began to ring in celebration: the war was finally over. This “short” conflict—as it was predicted by the military—had dragged on for 52 months, inflicting a wave of unprecedented suffering on the people in all countries involved. Those 1560 days of hell changed the world in every respect—demographic, geopolitical, economic, social, and cultural—and opened wounds that would take a long time to heal.

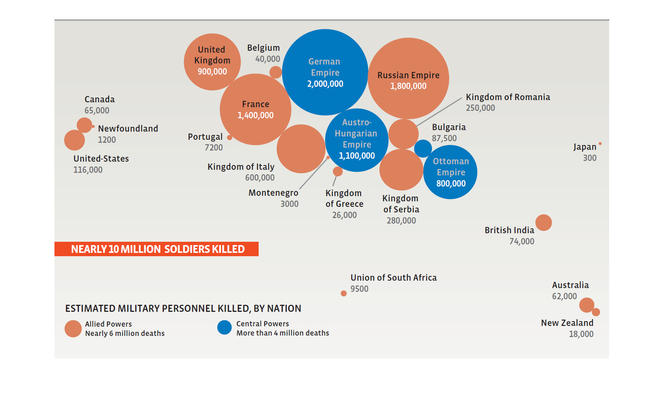

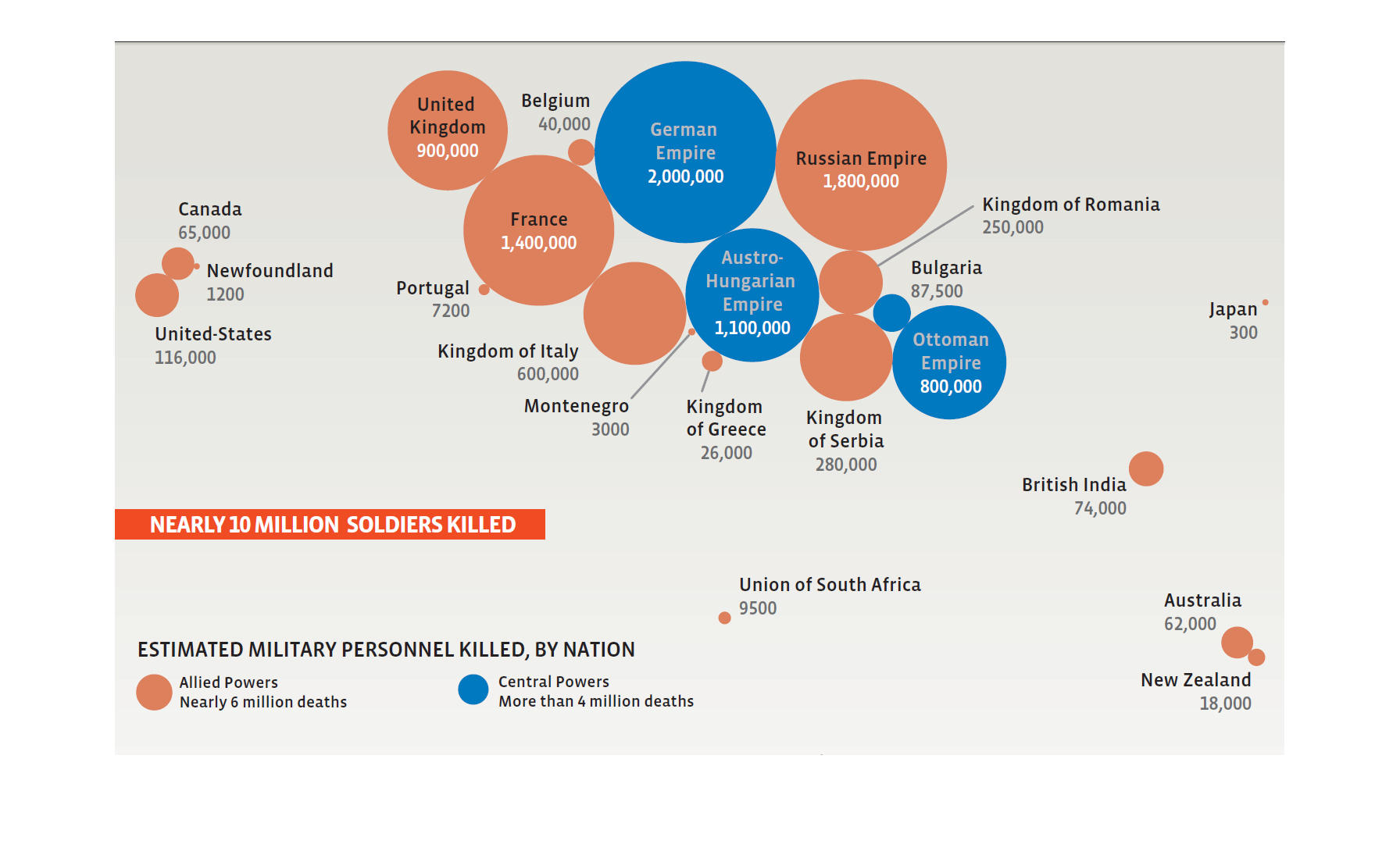

In a Europe deprived of millions of births, the human toll was particularly high. France alone lost 1.4 million soldiers “to the enemy.” Despite the re-annexation of Alsace-Lorraine (on the Franco-German border), which had been lost in 1871, four years of low birth rates had left a gap in the population pyramid. To offset the losses that had decimated its population, France experienced a wave of immigration in the 1920s, mainly from Poland, Italy, and Spain, and became the world’s second biggest migrant destination after the US. Meanwhile, Britain was mourning the loss of 800,000 “Tommies,” including soldiers from the Dominions. Germany lost more than 2 million men, Austria-Hungary nearly 1.5 million, the Russian Empire 2 million... The violence of the war, which claimed a total of 10 million lives and reached as far as the oceans and the sands of the Arabian desert, also took the lives of many non-Europeans, including 80,000 Americans in 1918 alone. To these grim statistics must be added, for all of Europe, some 6.5 million casualties, among which hundreds of thousands left blind, disfigured, or deprived of a limb, plus 8 million orphans, some 4 million young widows and several million bereaved parents.

Financial collapse

The economic and financial situation was just as worrying. Beyond the material damage—which was staggering, with 2.5 million hectares of farmland devastated, 60,000 kilometers of roads and hundreds of thousands of buildings destroyed in France alone—the horrific ordeal of the conflict had left Europe bankrupt. While the war was a boon for certain industrial sectors, like aeronautics, chemicals, and the car industry, it swept away the gold standard1 and with it the stability of Europe’s currencies. “All nations involved waged war on credit, relying on domestic loans but also, as far as France was concerned, on money borrowed from outside the country,” explains Isabelle Davion, from the IRICE2 laboratory. Whether to fund the war effort, repay debts, finance reconstruction, compensate those entitled to damages or pensions or, in the case of Germany, pay reparations, the European countries, whose gold reserves were depleted, resorted to printing money. They began producing currencies that had virtually no intrinsic value and depended solely on the confidence of the economic agents that used them. Inflation swept across Europe and gained momentum, reaching its climax in Germany, where in November 1923, one US dollar was valued at 4.2 trillion marks. The trauma of this period of hyperinflation would haunt the German collective memory for years to come.

To put an end to this devastating spiral and stabilize the currencies, each country devised its own solution—with varying success. In 1925, Britain restored the pound to its pre-war parity, in other words a fixed weight in gold, and paid the price for it. Its products became more expensive, which hindered exports, and the country’s austerity policy inflicted hardship on the lower classes. France devalued the Franc by 80% in 1928, a tough measure for savers who had placed their gold in government loans or national defense bonds, and were henceforth paid back in depreciated currency. Germany and Austria created the Reichsmark and the Austrian schilling in 1924, two new currencies whose value was pegged partly to gold and partly to the US dollar and the pound sterling.

Impervious to the monetary turmoil, the US, which had lent some $10 billion to the Allies and was Europe’s biggest creditor, now emerged as the world economic leader. London was no longer the center of capitalism. New York, the emblem of a thriving and booming country, became the “capital of capital.” Japan, by selling goods to the Allies, had seen its industrial production rocket by 72% between 1914 and 1919. But the Japanese economy, although still prosperous, began to suffer from the effects of global competition in 1921, when European products were re-introduced on the Asian market.

The rise of authoritarianism

The heritage of WWI was also political: European monarchies were swept away by the winds of defeat, along with the great dynasties that embodied them (Habsburg, Hohenzollern, Romanov, etc.). The German, Austro-Hungarian, Russian, and Ottoman empires collapsed. A host of republics (German, Austrian, Polish, Hungarian, Baltic)—some only short-lived—and new states (including Yugoslavia, Czechoslovakia, and Turkey) rose from the ashes of the old aristocratic structures, redrawing the political frontiers of a continent where minority rights were guaranteed by peace treaties.

A new geopolitical order, founded on the basic principles of liberal democracy, emerged in Europe. It promoted the idea that countries should resolve their conflicts peacefully, as advocated by the League of Nations established by the Treaty of Versailles. Signed in 1919 by Germany and the Allies, this treaty, the most important post-war peace agreement, included clauses designed to reduce Germany’s power in all areas—military, economic, geopolitical—for the sake of establishing a more balanced Europe and meeting France’s legitimate demands for greater national security.

Yet this was easier said than done. The absence of the US from the League of Nations,3 headquartered in Geneva, considerably undermined the power of this intergovernmental authority, whose “positive role is too often overlooked, for example in the financial salvaging of Austria in 1922,” notes Davion.

Mostly, this new European order, further weakened by the global economic crisis of 1929, exacerbated nationalist feelings in the countries that had been defeated (the vast majority of Germans believed that they had been forced into a “shameful” peace) or otherwise frustrated by the outcome of the war (like Italy, whose territorial claims were not all met). The interwar period was marked by the gradual replacement of republican governments by authoritarian regimes, so much so that by 1938, Czechoslovakia was the only republic left in central Europe. Peace failed because “the treaties were not given enough time to fulfill their purpose,” Davion believes. Albeit imperfect, they were extremely flexible, giving Europe’s new rulers the ability to introduce changes if necessary. But the men who drafted these treaties were not those who executed them, as the former had either been ousted by the electoral process—as in the US and France—or had withdrawn to avoid assuming their responsibilities. In Britain for example, Lloyd George disparaged the Treaty of Versailles immediately after signing it. Soon, only opponents were heard. Few were left to defend the peace agreements, which did not fit in the Europe of the 1920s and 1930s. “World War II broke out because the Europe of Versailles no longer existed,” Davion concludes.

The advent of modern art

What about the cultural legacy of World War I? In the countries at war, many artists from all fields were plunged into the horror of the trenches, only to return wounded—or no return at all. At the same time, the war spawned a multitude of great works of art, often with a pacifist theme, by writers, painters, and filmmakers. These include Aragon, Dufy, and Renoir in France, Chagall in Russia, J.R.R. Tolkien in Britain, George Bernard Shaw in Ireland, Karl Kraus and Stefan Zweig in Austria, and Ernst Jünger, Georg Grosz, and Otto Dix in Germany.

Yet did the war redefine artistic norms? “This is the subject of historiographical debate,” says André Loez, a French historian, professor, and WWI specialist. “In short, there are two opposing theories. One states that World War I, the first modern war, marked a turning point in Western cultural history and set the stage for the genesis of modern art. This line of thought links the savagery of the conflict to the birth of Dadaism, and then to the rise of Surrealism in the 1920s. Another theory, which is more widely accepted today, holds that the Great War accelerated the emergence of modern art, but that the movement predated the conflict. After all, the Futurist Manifesto was published in 1909, Kandinsky produced his first abstract paintings in the 1910s, and Apollinaire published Alcools in 1913.”

Keeping the memory alive

In France, since the 1980s and 1990s, “the children, grandchildren, and now great-grandchildren of veterans have been tracing the history of their ancestors who fought during World War I,” explains Nicolas Offenstadt of the LAMOP.4 “They publish the veterans’ letters and diaries online, follow the routes taken by their regiments, and even visit the battle-fields where they faced enemy fire.” The memory of World War I is still vivid in the victorious countries, especially the old nations like France and Britain. Similarly, the conflict continues to exert a strong symbolic influence in the US, Canada, and Australia, which had then fought for the first time as a federated nation, notably in Gallipoli (Turkey), in April 1915.

“In Russia, the accounts of World War I soldiers were largely obscured in the collective memory throughout the communist era,” says Offenstadt. “Today, they serve patriotic purposes.” German memory, on the other hand, “is marked primarily by the 1933-45 period and the challenges of reunification, which leaves little room for 1914-18.

More on the same topic:

WWI: Origins of a Conflict

Laboratories at War

- 1. The gold standard was a system whereby central banks, using their gold reserves, guaranteed the redemption of banknotes presented at a bank and whose value was pegged to the precious metal. On the eve of the war, this system was in effect in 59 countries, allowing them to securely exchange their currencies.

- 2. Identités, relations internationales et civilisations de l’Europe (CNRS / Université de Paris-Sorbonne / Université de Paris-I).

- 3. In March 1920, the American Senate refused to ratify the Treaty of Versailles, preventing the US from joining the League of Nations.

- 4. Laboratoire de médiévistique occidentale de Paris (CNRS / Université de Paris-I).

Explore more

Author

Philippe Testard-Vaillant is a journalist. He lives and works in south-eastern France. He has also authored and co-authored several books, including Le Guide du Paris savant (Paris: Belin) and Mon corps, la première merveille du monde (Paris: JC Lattès).