You are here

Science and Peace

1870 and the “triumph of German science,” (to quote Ernest Renan) 1914-1918 and the Great War of chemists, 1939-1945 and the mobilization of physicists… Add to this the countless conflicts that have engulfed entire regions throughout the world, and one can easily see that recent history provides a wealth of evidence of the ties between scientists and warfare. But older history is also filled with similar examples. For current illustrations, a quick glance at any newspaper provides ample evidence! But what of peace in all of this sad litany? Well those grim, nationalistic and murderous scientists (as some would have you believe) have also expressed concern, and 2017 offers an opportunity to examine one of the most original initiatives in this field.

Einstein, Russell and… Pugwash

Pugwash, you say? It is a village in Nova Scotia (Canada), known for its fishermen, its forest and its salt mines. When you get there, posters greet you with this message: “World Famous for Peace.” Not that Pugwashians have any ego problems: their pride is well-founded and is based on their town having played host in 1957 to the first “Conference on Science and World Affairs.” The meeting, organized in his birthplace by philanthropist Cyrus Eaton, brought together 22 eminent scientists, from 10 different countries, including the 5 permanent members of the UN Security Council.

But it was not by mere chance that Pugwash was chosen to host the conference. Two years earlier, the Russell-Einstein Manifesto had been penned by mathematician Bertrand Russell and physicist Joseph Rotblat, and was signed by Albert Einstein days before he died, followed by other Nobel prize winners, including Frenchman Frédéric Joliot-Curie.

The Manifesto condemned weapons of mass destruction, in particular the H bomb, calling upon world leaders to seek peaceful solutions in settling their disputes, and it proposed to organize a conference of scientists eager to work towards this end.

On 9 July 1955, Russell began his press conference on the Manifesto with these striking words: “I am bringing the warning pronounced by the signatories to the notice of all the powerful Governments of the world in the earnest hope that they may agree to allow their citizens to survive.” For his part, Rotblat, who had made history 10 years later as the only physicist to have turned his back on the Manhattan Project, emphasized an equally striking passage from the manifesto: “Remember your humanity, and forget the rest.” Immediately afterwards, he began working with Eaton on organizing the first conference.

A winning strategy

This conference was initially to have been held in 1956, but world events decided otherwise: the organizers had to wait for the Suez Crisis to pass, the latest upset to date in the world’s march along the good road. When they finally assembled in 1957, the participants agreed on the creation of a permanent movement, which took its name from the Canadian village, and offices sprang up around the globe: Pugwash-France, for example, was created in 1964 under the auspices of such public figures as Raymond Aubrac, Alfred Kastler, André Lwoff and Jules Moch.

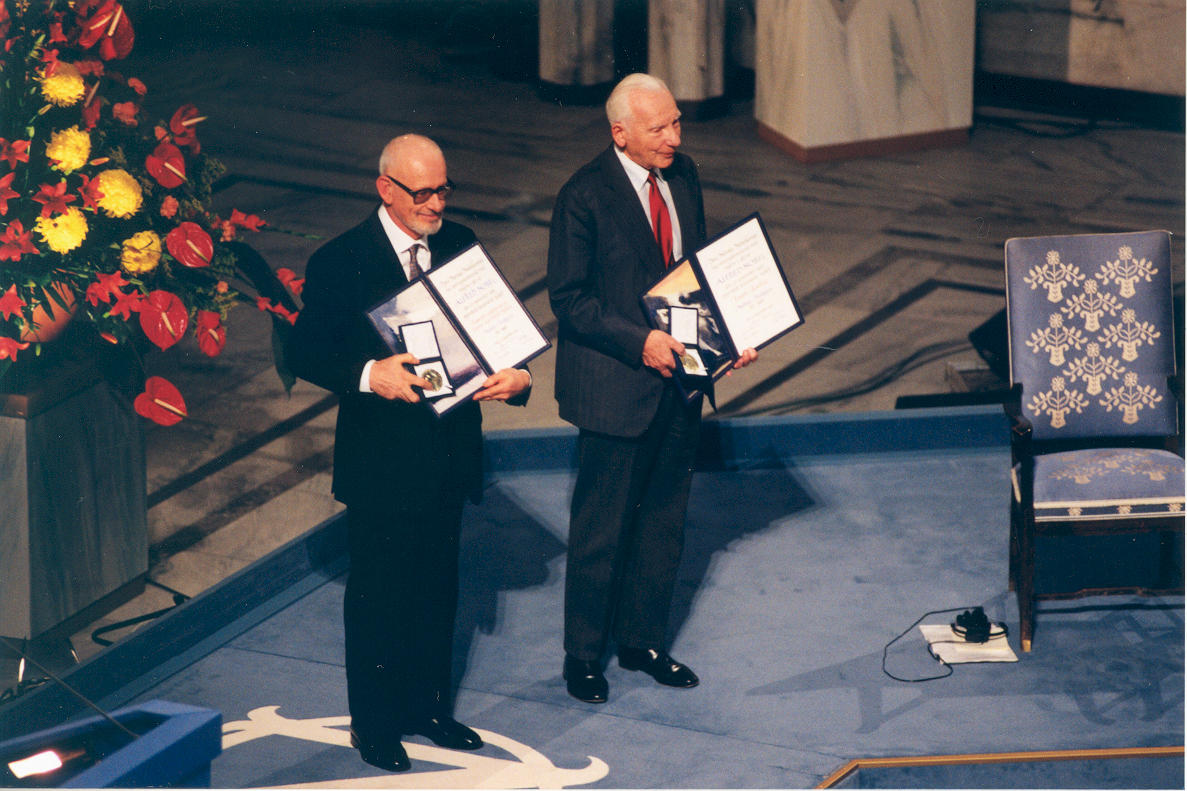

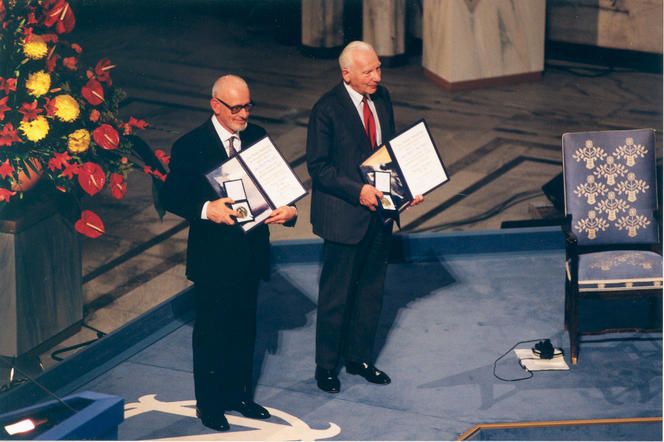

Above all, Pugwash’s members were united in preferring sober and discreet action over large-scale public manifestations, and this proved to be a winning strategy since the movement can claim to have played a part in the creation of numerous agreements, from the Partial Test Ban Treaty (PTBT) to the Chemical Weapons Convention. On top of this, the Nobel Peace Prize 1995 was awarded jointly to the organization and its main founding father, Joseph Rotblat.

After the end of the Cold War, Pugwash did not take a back seat. It was not just the specter of nuclear war, itself far from disappearing, that hung over the world. Other problems such as environmental issues gradually emerged, and they too pose a threat to the future of humanity. But the core concern of the movement continues to be peace, and its ambition is to rewrite the old Latin adage: si vis pacem… para pacem!1

- 1. Translation: If you want peace, prepare for peace. The original adage in fact states: si vis pacem… para bellum (“If you want peace, prepare for war”).

Explore more

Author

Denis Guthleben specializes in the history of science and scientific research. He focuses on the politics, institutions, actors, and programs that have shaped it from the French Third Republic to the present day. He has authored three books (publisher: Armand Colin):

- Histoire du CNRS de 1939 à nos jours. Une ambition nationale pour la science ("A history of the CNRS from...