You are here

Saving Afghanistan's Incredible Heritage

For the last thirty years, Afghanistan has been associated with images of war, of the Soviet occupation, civil strife, and the Taliban—to the point of concealing the extent to which the country once fired the imagination of archaeologists and adventurers of every sort. It was there that Alexander the Great, who had set out to conquer Asia, is said to have met and married the beautiful Roxana around 330 BC. Buddhism found fertile ground there too, yielding some of its most beautiful works of art, such as the tragically renowned Buddhas carved into the cliffs of the Bamiyan valley, and destroyed by the Taliban in 2001. It was also through Afghanistan that goods, such as tea, spices, precious stones and silk, travelled for centuries along the Silk Road. Located at the crossroads between central Asia, the Persian world and the cultures of the Indian sub-continent (Pakistan and India), Afghanistan has always been a source of envy, and with good reason: it is one of the countries that boasts the greatest number of mines of copper, gold, silver and even of lapis lazuli, a semi-precious stone found in the Mesopotamian tombs of Ur and in the jewellery of the Egyptian Pharaohs.

Julio Bendezu-Sarmiento, a CNRS researcher and French-Peruvian archaeologist, has headed the French Archaeological Delegation in Afghanistan (DAFA) since 2013.1 He explains why it is urgent to list Afghanistan's archaeological heritage, as a growing number of economic development projects are underway, such as the gas pipeline planned to cross the south of the country, and looting has never been so widespread.

The French Archaeological Delegation in Afghanistan (DAFA) is the only foreign archaeological team with a permanent presence in Afghanistan. Why?

Julio Bendezu-Sarmiento: Our offices are located in Kabul, in an old building that houses a research center, a library containing 20,000 books, a restoration and a photo laboratory and storerooms. Today, we are quite simply the only foreign archaeologists still working in the country: since the bomb attack that killed 90 civilians in Kabul's diplomatic quarter in spring 2017, every other international scientific team has left. This has to do with our very close ties to Afghanistan. The DAFA was set up in 1922 at the request of King Amanullah, when the country was just beginning to open up to the outside world: in fact, the archaeologists got here before the French diplomats!

An agreement signed between the French and Afghan governments conferred the DAFA exclusive rights to carry out excavations in Afghan territory, and established that objects would be shared equally between the two countries—which is why many Afghan artefacts can now be seen in Paris at the Guimet Museum of Asian Art and at the Louvre's Department of Islamic Art. This was still very much a colonial view of archaeology, which people would find out of place today! The DAFA lost its monopoly on excavations in the 1960s, and was even forced to leave the country during the Soviet occupation and the civil war that followed from 1982 to 2002. Since we returned in 2003, our role has changed considerably and is now more pragmatic.

What do you mean by ‘pragmatic’?

J B-S: While we continue to conduct very rapid excavations in the field—never for more than two weeks for security reasons—we also provide expertise and advice to the Afghan authorities, who are now showing greater interest in their archaeological heritage. The current president, Ashraf Ghani, is a doctor in anthropology, and sees this patrimony as an opportunity to build a great national narrative that can reconcile all the peoples that make up this country: Pashtuns, Hazaras, Tajiks, Turkmens, Uzbeks and so on.

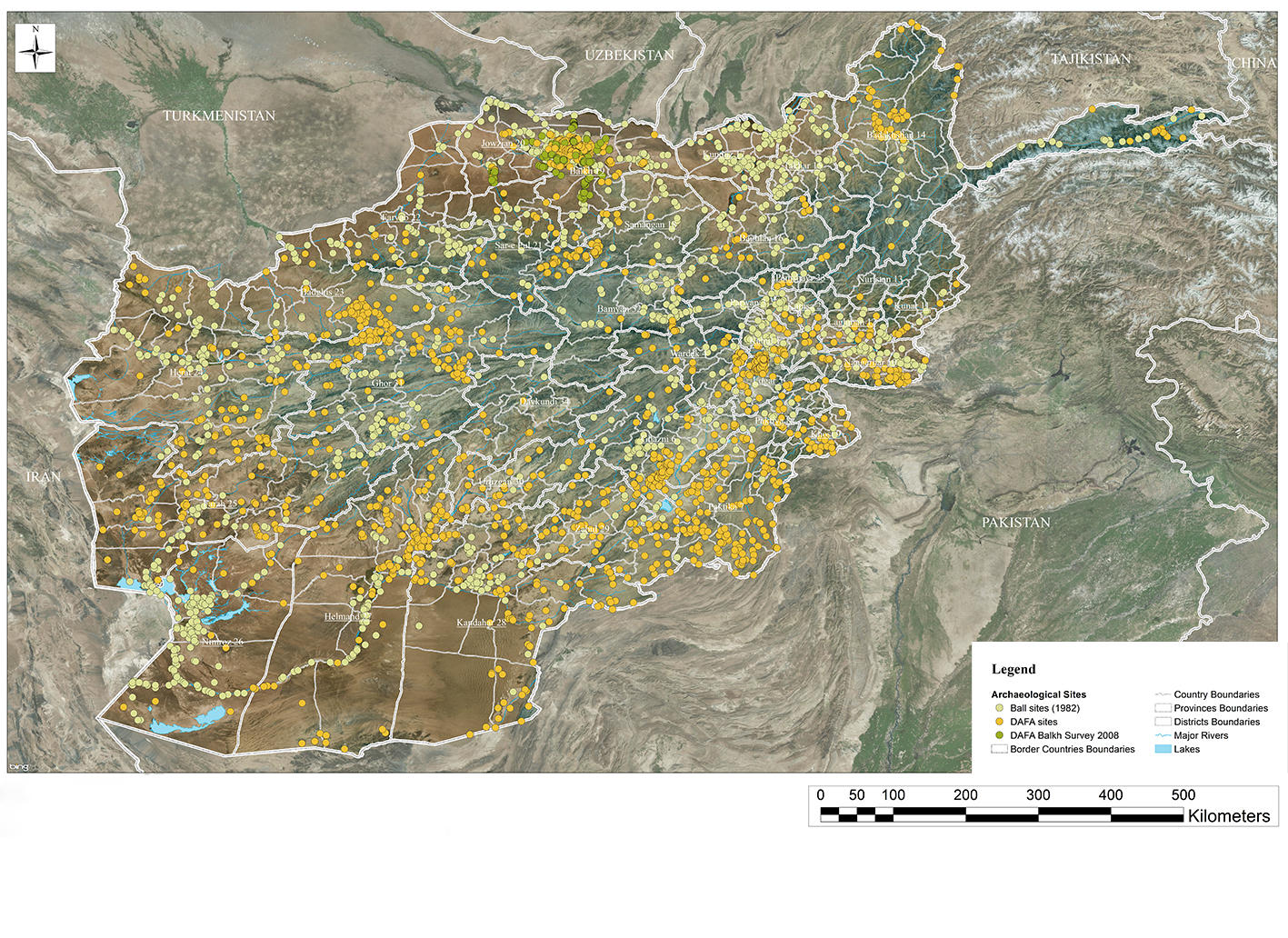

Specifically, we take part in the Afghan Ministry of Information and Culture’s ’Stolen Objects Commission’ to help distinguish between genuine antiques and fakes—looting of archaeological sites is frequent in the country—, and assess all major development projects related to urban planning, road construction and mining. Afghanistan boasts 26 exceptional mines, of gold, copper, iron, rare metals, etc, and the government hopes to rapidly hand over their exploitation to foreign companies. In order to make a fully-informed decision, the Afghan authorities entrusted us in 2014 with the mission of producing a comprehensive archaeological map of the country, which will make it possible to draw up an exhaustive inventory of all its ancient sites.

Does the decision to map the entire Afghan archaeological heritage have anything to do with the discovery of Buddhist remains at Mes Aynak, the copper mine entrusted to the Metallurgical Corporation of China in 2008?

J B-S: Yes, partly. The Mes Aynak mine, located about 30 km southeast of Kabul, is the world’s second-largest copper deposit. In fact, ‘aynak’ means ‘copper’ in Pashtun, and it has probably been worked since ancient times. The first traces of a Buddhist site were found by the DAFA in 1976, during archaeological and mining surveys. That is why the Afghan government asked the Metallurgical Corporation of China, through the World Bank, to fund preventive excavations before starting to exploit the mine.

What international teams of archaeologists discovered was way beyond what anyone could have imagined: a city of several square kilometers that included monasteries, stupasFermerThe stupa is a mound-like architectural structure, a stack of bricks or stones, at the heart of which was originally enclosed a relic of the Buddha., fortresses, administrative buildings, dwellings, etc, and which had not been documented anywhere in the historical texts of the region. Hundreds of terracotta statues of Buddha were also brought to light. The mining project was suspended—it is still on the agenda as I speak—and, as of 2011, the World Bank and Unesco decided to join forces with the DAFA to evaluate the 26 mining sites listed in the country, in particular by funding the purchase from Airbus of aerial survey photographs taken around mining concessions. Together with our Afghan and international partners, we are also preparing an initial compendium on the archaeological significance of the Mes Aynak mine.

Specifically, how do you go about drawing up an archaeological map of the country?

J B-S: Solely by remote detection. Going into the field would require a huge amount of time, and we have neither the means nor the security conditions necessary to carry out systematic excavation campaigns. We only work with photographs: either drone or aerial, like those from Airbus, declassified satellite maps provided by NATO, and so on. In all, we have several thousand images, each of which must be studied with the naked eye, which takes time and a certain amount of skill: buildings in Afghanistan have always been made of mud, and are therefore more fragile and harder to spot. This is one of the reasons why the DAFA’s first archaeologists had so much trouble finding traces of the Greek presence in Afghan territory—especially in the region of Bactra (Balkh) where it was known that Alexander's generals had founded a colony.

Foucher, the first director of the DAFA (1922-1925), went so far as to speak of the ‘Greek mirage’! The problem was that he was looking for stone buildings, as in the rest of the Greek world, when in fact only the decorative elements—like the columns and their capitals—were made of marble or stucco. The first Greek site was discovered accidentally in 1961 at Ai-Khanoum, at the border with Tajikistan. During a hunt organized for the last king of Afghanistan, Mohammad Zaher Shah, one of the helpers found a capital of undeniably Corinthian style. After more than ten years of excavations, an entire city had been uncovered, with its forum, its gymnasium and so on. As for Bactra, the first Greek remains were only unearthed there in 2007!

How do you identify remains on a satellite map?

J B-S: You have to be very familiar with the layout of the types of buildings you are looking for. Caravanserais, for example, where merchants travelling the Silk Road could stop for the night, have a characteristic architecture, with an enclosed courtyard for animals, a small mosque, and rooms surrounding the courtyard. In actual fact, many of the sites we come across have already been broken into by looters and bear the marks of their visit: they are literally riddled with holes, which with a little practice can be seen very clearly in aerial photos. The looters—warlords, or just peasants who steal occasionally to make ends meet—look for the objects that sell best, such as coins and pottery.

How many sites have you already listed?

J B-S: When the DAFA left Afghanistan following the Russian invasion, nearly 1300 sites had already been discovered and published. We suspected that there were many more. The entire country is an open-air museum, and wherever you dig you are sure to find something!

Since the project began in 2014, our 20-strong team (mostly Afghan researchers and technicians) has already spent hundreds of hours working on it. To date—and we are far from finished—we have brought to light nearly 5000 sites, which are shown on the map in three different colours: those in yellow have already been excavated, those in blue have only been identified, while those in red have been discovered recently and still require identification. The idea is to produce a geographic information system (GIS). Every point on the map provides access to a database of available information about the site.

A final question: what about the planned gas pipeline that is to cross Afghanistan?

J B-S: Announced 20 years ago and continually postponed, the aim of the TAPI (Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India) gas pipeline project is to open up Central Asia by providing outlets for its energy resources, and to secure India's gas supply. The shortest route is through western and southern Afghanistan, which is partly under Taliban control. Hence the delays. However, operations are supposed to start any day now, which is why the Afghan government has asked us to step up our efforts to identify archaeological remains in the region. They also want us to monitor the work in order to ensure the protection of this heritage. I am not sure whether the French Foreign ministry will let us travel there, but for now we are carrying out consultancy and training missions in neighboring Turkmenistan and are still waiting for accurate maps of the TAPI route through Afghanistan.

- 1. The DAFA is a French research institute abroad (IFRE) reporting directly to the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs.