You are here

Gravitational wave detections spark great expectations

It's now been ten years since gravitational waves were first detected. How do you feel, as someone who was involved from 1998 onwards in all the preparatory work that led up to this observation?

Marie-Anne Bizouard1: I joined the gravitational-wave community at a time when few people would have bet on our chances of success. So when we started collecting data in 2015, we took nothing for granted. And yet, within just a few days, we detected our first signal. That was totally unexpected and at first we thought it was probably just an artificial event injected into the data, something frequently done in order to test our instruments.

However, once the spokesperson for the collaboration confirmed that this wasn't the case, and after we'd spent a few weeks checking the detectors we were all overcome by a huge sense of elation, as pioneers who had been working in difficult conditions for over 20 years. So much so that we all felt that this discovery belonged to us, and to us alone! For me, just thinking back on it on this anniversary conjures up the euphoria we all felt at the time.

What exactly are gravitational waves?

M.-A. B.: In the general theory of relativity first put forward by Albert Einstein in 1915, gravity results from distortions in spacetime, which is regarded as a kind of medium with quasi-material properties. Thus, if a sufficiently violent gravitational event occurs, spacetime can start to vibrate, in the same way as a stone thrown into water produces ripples on its surface. Einstein predicted the existence of such waves when he formulated his theory, while at the same time showing that they would be so weak as to make their detection virtually impossible.

So, how do you go about detecting gravitational waves?

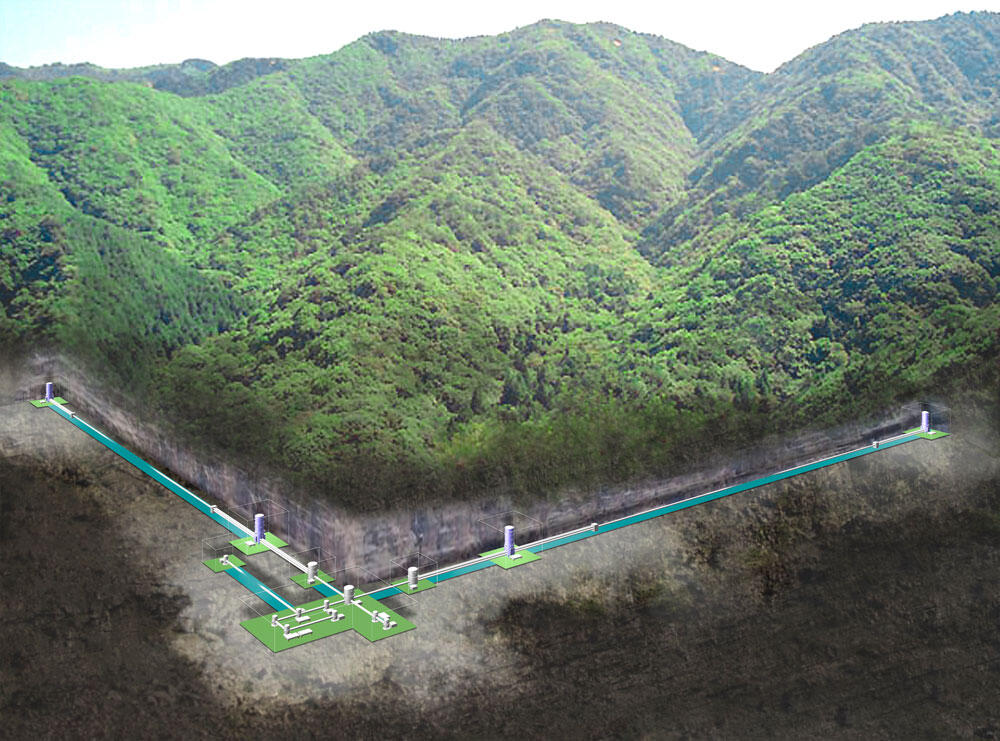

M.-A. B.: In order to spot even the most powerful gravitational cataclysms in the Universe – such as the merger of two black holes, the phenomenon that led to the first observation of gravitational waves – you need to be able to measure vibrations in space corresponding to changes in length 10,000 times smaller than the size of a proton. To achieve this, the beam from a powerful laser is split into two, with each fraction travelling back and forth several times along one or other of the two arms of an interferometer, each of which is several kilometres long, before being recombined.

When a gravitational wave passes through the interferometer, one of the arms 'lengthens' and the other 'shrinks', which can be detected by means of the diffraction pattern obtained by recombining the two beams. This is the principle behind the three gravitational wave observatories that are currently fully operational: two LIGO observatories in the US, and Virgo in Italy.

Building these facilities and successfully detecting gravitational waves must have been colossal challenges!

M.-A. B.: Indeed. It should be borne in mind that these are extremely complex experiments, using totally unprecedented detectors that permanently act as prototypes at the cutting edge of technology. For the record, when Adalberto Giazotto and Alain Brillet dreamt up Virgo in 1985, they originally named it the Very Improbable Radio-Gravitational Observatory!

The success of the project is due to a major international effort, in which France and the CNRS played a significant part, and to the tenacity of Alain Brillet, who was awarded the CNRS Gold Medal in 2017. It was he who first demonstrated the possibility of increasing the power of a laser by sending the beam on multiple round trips, who understood the advantage of using an infrared laser, and who managed to persuade the CNRS to set up a laboratory in Lyon (southeastern France – Ed’s note), headed by Jean-Marie Mackowski, to produce optics with the reflectivity required for Virgo and LIGO.

All this led to the 2015 breakthrough. Just how important was this?

M.-A. B.: It was probably one of the greatest discoveries of this century, on a par with that of the Higgs boson in 2012, the particle that endows fundamental particles with mass. The announcement of its discovery in Washington in February 2016, made a huge splash, both in the media and among scientists.

As well as the discovery of gravitational waves as such, this first detection also marked the birth of gravitational-wave astronomy.

M.-A. B.: The detection of gravitational waves opened up access to phenomena that had never ever been observed, starting with the merger of two black holes. And, right from the start, we went from one breakthrough to another, beginning with the 2015 observation, which identified two black holes with masses 29 and 36 times that of the Sun, which was far greater than expected.

Subsequently, during the second observing run in 2016-2017, we spotted the first merger of two neutron stars, which are objects formed by the gravitational collapse of the cores of certain massive stars. That observation also marked the birth of multi-messenger astronomy.

Then, during the third run, in 2019, we saw the merger of two stellar black holes so massive that we may have discovered the first signs of the forerunners of the supermassive black holes found at the centres of galaxies.

At the same time, the frequency of detections has steadily increased, hasn't it?

M.-A. B.: Yes, indeed. During the first run, we made three detections. The number then increased to around ten on the second run, just under a hundred during the third, and some 300 during the current one. So, in 10 years, we have gone from an era of discovery to one of precision measurements.

With run 4 drawing to a close at the end of the year, what new discoveries have you made so far?

M.-A. B.: Although we've only analysed and published a third of the data, we already have some extremely interesting results. Following the finding I have just mentioned in run 3, we've witnessed several mergers of black holes of around a hundred solar masses, giving us an initial access to statistics on their mass and rotation.

This is important, because we need to know whether such black holes result from stellar collapse or alternatively from the coalescence of smaller black holes. And it turns out that, for some of these events, their properties tend to support the second scenario. That's good news, because it would mean that we are seeing stage 2 of a hierarchical merger process, which would provide us with a mechanism for the formation of giant black holes at the centre of galaxies.

In addition, over and beyond statistical considerations, we're continuing to spot some remarkable individual events. In particular, we observed a merger with a signal-to-noise ratio of 80, which is a very strong signal, enabling us to perform detailed tests of general relativity – which has once again proved to be extremely robust!

Have the detectors undergone any changes over the past ten years?

M.-A. B.: Yes, they are constantly being improved in order to increase their sensitivity, expanding this window onto the Universe and currently enabling us to see events as far as two billion light years away. Every improvement is the sum of many small things that are extremely difficult to achieve, aimed at reducing experimental noise, whether of seismic origin or related to the quantum nature of light.

In addition to Virgo and LIGO, there is now the Japanese KAGRA interferometer, which should join the end of run 4, even if its role is still marginal, together with the LIGO-India project which has just been launched. In other words, we are seeing the birth of a robust and promising worldwide ecosystem of gravitational-wave observatories.

But there are some short-term uncertainties, aren't there?

M.-A. B.: Yes there are. With regard to Virgo, our programme of upgrades planned for run 5 starting in 2028, has recently been scaled back. As for LIGO, part of its funding could be adversely affected by the budgetary choices of the new US administration, which we'll find out about in November. In any case, we are confident that our detectors are performing well, and we are already looking ahead to the future.

What's next?

M.-A. B.: Beyond run 5, the Virgo and LIGO interferometers will upgrade respectively to their so-called Virgo_nEXT and A# versions. The idea is to take the experiments to their limits, and to test all the technologies for the next generation of instruments currently in development.

By 2040, Europe could be equipped with an interferometer with three ten-kilometre-long arms (the Einstein Telescope), which will boost detection sensitivity by a factor of 10. Similarly, the US is contemplating the construction of a ground-based instrument with arms 20 to 40 kilometres long, as compared to 4 and 3 kilometres for LIGO and Virgo. Then there's the European Space Agency's LISA space-based interferometer, which is scheduled for launch in 2035.

The combination of all these instruments will provide access to the entire observable Universe and to the whole gravitational-wave frequency spectrum.

What does the future hold?

M.-A. B.: Discoveries in areas such as tests of general relativity, the study of matter in extreme states, along with stellar and galactic evolution, all of which are of interest to astrophysics, cosmology and fundamental physics alike.

When are these discoveries expected to happen?

M.-A. B.: While it is impossible to predict the explosion of a supernova, we do believe that we are on the verge of observing what is called the 'stochastic gravitational wave background', i.e. the background noise caused by all the astrophysical events that produce gravitational waves. According to some estimates, this could happen during the fifth run of LIGO-Virgo.

If successful, this would mean that in principle we will be able to detect the stochastic background of cosmological origin, in other words the gravitational waves emitted by the Universe at the moment of the Big Bang. After letting us see the merger of two black holes as predicted by general relativity, gravitational-wave astronomy would then open the way to another prediction of Einstein's theory of gravity, namely, the birth of the Universe.

- 1. Research professor at the ARTEMIS laboratory, (CNRS / Observatoire de la Côte d’Azur / Université Côte d’Azur).

Explore more

Author

Born in 1974, Mathieu Grousson is a scientific journalist based in France. He graduated the journalism school ESJ Lille and holds a PhD in physics.