You are here

The Big Bang within the reach of telescopes

The screen shows white streaks bursting out like fireworks in the night sky: "Thanks to this image, we now have a clear view of where we are in the Universe, of the place in which we live," says an upbeat Aurélien Valade, an astrophysicist at the Marseille Particle Physics Centre (CPPM)1. By analysing the position and speed of the 56,000 galaxies in the Cosmicflows-42 survey, he and his team have succeeded in mapping the gravitational basins of attraction in the local universe, which enabled them to determine that the Milky Way lies within the Shapley supercluster.

This was not only made possible thanks to the new enriched version of the Cosmicflows catalogue, but also by using an improved method for analysing the observational data. This wealth of material is providing theorists with new tools to tackle the question of the origins and evolution of the Universe. To date, all the data appears to confirm the broad outlines of what is known as the Standard Cosmological Model: 13.8 billion years ago, our Universe emerged from an extremely hot, dense state which, as it expanded, cooled and started to take on structure, gradually giving rise to the vast web of galaxies that we see today.

While there is still broad agreement about this model, it remains sketchy and leaves many questions unanswered. What happened in the very first moments of the Universe? How did matter first appear? What forces caused it to take shape?

Mapping the local universe

Compared to this, the question of our own location in the Cosmos, determined by painstakingly mapping the galaxy clusters present within a radius of a billion light years around us, might appear trivial. However, this information contains valuable clues about the processes at work in the Universe.

This was the reason astrophysicists set out to measure the velocity of a sample of galaxies, from which they deduced the structure of the gravitational flows that pull them to the densest regions. Until then, this type of analysis had been based on a statistical method which, as Valade explains, "requires the formulation of a number of assumptions, and reliance on a series of approximations that boils down to leaving out part of the information contained in the data".

To get around this problem, scientists have developed a method called “probabilistic inference”. Based on artificial intelligence, it involves numerically generating countless configurations and assigning each one of them a probability of being consistent with the observations.

"In this way we obtained 1,000 configurations in keeping with the data, which ultimately makes our map of gravitational basins extremely robust," the researcher says. As a result, while the scientists were able to confirm the existence of the Laniakea supercluster, in which our Galaxy was thought to be located, their findings – unlike those published previously – showed that the Milky Way is actually more likely to lie within the much larger Shapley supercluster.

Refining the parameters of the Standard Model

"We initially applied our technique to simulated data," Valade says. "Then, with our reconstruction of the gravitational basins in the local universe, we tested it for the first time on real data. And we are now using it to determine precisely a poorly known parameter in the Standard Cosmological Model." In this model, the parameter, called “fσ8”, describes the degree of aggregation of matter in the Universe. Its value determines the number and size of galaxy clusters, as well as the entire gravitational structure of the Universe.

To measure it, the astrophysicists at the CPPM have teamed up with Mickaël Rigault, an astrophysicist at the Institute of Physics of the 2 Infinities (IP2I)3, in Lyon (southeastern France), where he heads the cosmology research group of the ZTF collaboration. ZTF aims to create a catalogue of several thousand type 1a supernovae, stellar explosions whose luminosity is constant, making it possible to determine their distance precisely and, in this way, obtain a better approximation of the value of fσ8.

And this is only just the beginning. As Dominique Fouchez of the CPPM predicts, "the development of new statistical methods such as probabilistic inference, combined with the massive influx of new data from large surveys, like those from the ground-based Vera C. Rubin telescope and the Euclid satellite, will provide extraordinary opportunities for new discoveries and challenges to our current understanding".

How inflation made the Universe flat

This view is shared by researchers who focus on the very earliest moments of the Universe. They believe that the future catalogues, which will include hundreds of millions of galaxies and other celestial objects, will enable them to find evidence of the birth of the Cosmos, or more specifically, of a period called “inflation” which, between 10-36 and 10-33 seconds after the Big Bang, is thought to have seen the size of the Universe increase by a staggeringly large factor of at least 1026. This hypothesis, formulated in the early 1980s, has the advantage of solving several enigmas, including the fact that the Cosmos appears to be perfectly flat.

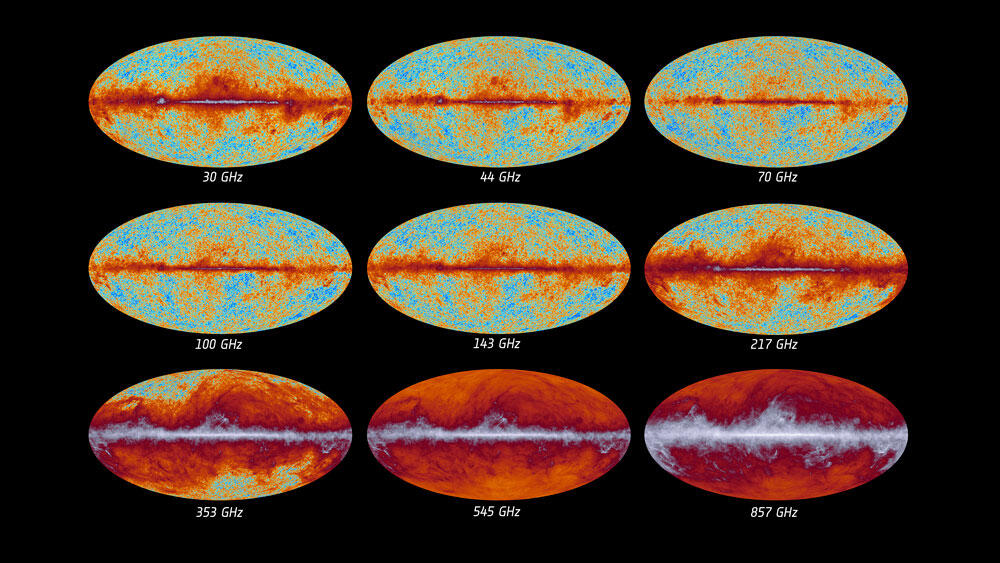

The general framework of inflation theory was validated by data from the Planck satellite which, some ten years ago, produced the most detailed map ever of the Cosmic Microwave Background (the first light emitted by the Universe, 380,000 years after the Big Bang). Despite this, scientists still don't know how inflation took place, why it stopped, or how the matter that makes up the Universe today emerged from this phase of exponential expansion.

From quantum fluctuations to the cosmic web

Part of the answer may lie in the comprehensive galaxy surveys currently being carried out. According to the inflation scenario, the large-scale structures of the Universe result from a “stretching” of the quantum fluctuations that existed in space-time at the very earliest moments. It is thought that it was around these fluctuations that matter then collapsed in on itself, forming stars, galaxies, and the entire cosmic web. "We're hoping that data about the distribution of matter in the Universe will be sufficiently precise for us to draw information about the details of the inflation scenario and its cause," says Sébastien Renaux-Petel, an astrophysicist at the IAP4.

This observational data will then need to be compared with that calculated using various models of inflation. Unfortunately, the equations from these models, which combine general relativity and quantum mechanics, are often fiendishly difficult to solve. To get around this, the researcher, together with Lucas Pinol, from the LPENS5, and Denis Werth, at the IAP, have recently proposed a numerical method that provides a way of calculating the observational implications of any theory of the primordial universe.

"Starting from a much simpler state of the Universe"

"Until now, researchers have tried to calculate the signal of interest at the end of inflation, at a time when the Universe was already very complex," Renaux-Petel explains. "Whereas we chose to numerically solve the entire evolution of predictable quantities, right from the beginning of inflation. This produces more data than needed but has the advantage of starting from a much simpler state of the Universe, at a time when space-time was subject only to quantum vacuum fluctuations." This ingenious approach could bring inflation within the reach of telescopes, and earned the three theorists the prestigious 2023 Buchalter Cosmology Prize.

Along with Angelo Caravano, a colleague at the IAP, Renaux-Petel recently proposed a formalism for studying inflationary models characterised by very high-intensity quantum fluctuations. Until then, this possibility was out of reach of the usual approximations, which only take into account low-intensity fluctuations. However, it is thought that at the end of the inflationary period, intense quantum fluctuations could have generated primordial black holes.

Initially proposed several decades ago by the English cosmologist Stephen Hawking, these non-stellar black holes were recently invoked to explain the discovery by the James Webb Space Telescope of an unexpected abundance of very old yet already extremely dense galaxy clusters.

In search of the Cosmic Gravitational Background

Theorists have taken advantage of this new method to explore various scenarios, some of which are particularly disconcerting. Whereas our local universe has long since emerged from inflation, some parts of the early Universe remain in an eternal inflationary state. "In this case, general relativity indicates that for an observer located in a region no longer undergoing inflation, those that still are would appear as black holes," Renaux-Petel points out. "This is the first time such a prediction has ever been made!" He and his colleague have calculated how very large-amplitude fluctuations could generate gravitational waves that might be spotted by next-generation detectors.

All this remains speculative but, as Danièle Steer, who heads the gravitational waves research group at the LPENS, points out, "with the commissioning of the Einstein Telescope, planned for 2040, and that of the space interferometer LISA, scheduled for launch in 2035, we might be able to detect a cosmic background made up of gravitational waves emitted by the Universe in its very first moments".

Such a gravitational background would enable astronomers to “look” back beyond the Cosmic Microwave Background, the very first light, consisting of photons emitted 380,000 years after the Big Bang. "This would provide us with information about inflation and, in particular, about the possible existence of primordial black holes," the astrophysicist says.

However, on the face of it, the earliest stages of inflation will forever remain beyond the reach of observation, which, as Steer’s colleague Vincent Vennin puts it, means that "today we have a general framework that allows for very high-amplitude quantum fluctuations during inflation. If this is confirmed by observation, for example by the discovery of primordial black holes, this framework will be further strengthened".

In that case, theory and observations would make it possible to go back in time almost as far as the Big Bang itself. We would then know not only where we live in the Universe, but also where we come from! ♦

See also:

James Webb illuminates the grey areas of astrophysics

Archaeology goes galactic

- 1. CNRS / Aix-Marseille Université.

- 2. https://indico.global/event/12931/book-of-abstracts.pdf

- 3. CNRS / Université Claude Bernard Lyon 1.

- 4. Institut d'Astrophysique de Paris (CNRS / Sorbonne Université).

- 5. Laboratoire de Physique de l 'École Normale Supérieure (CNRS / ENS-PSL / Sorbonne Université /Université Paris Cité).

Explore more

Author

Born in 1974, Mathieu Grousson is a scientific journalist based in France. He graduated the journalism school ESJ Lille and holds a PhD in physics.